archipelago

2021-02-23

17:47

river

2020-10-05

13:28

immense fahrenheit

2020-09-02

17:46

sinewave

2020-08-31

13:05

resonance

2020-07-03

10:58

corridor

2020-06-23

16:50

Chroma

2020-03-13

13:23

disintegration

2019-11-25

21:36

The discovery of the of the sea is a precious experience that bears thought. Seeing the oceanic horizon is indeed anything but a secondary experience; it is in fact an event in consciousness of underestimated consequences.

I have forgotten none of the sequences of this finding in the course of a summer when recovering peace and access to the beach were one and the same event. With the barriers removed, you were henceforth free to explore the liquid continent; the occupants had returned to their native hinterland, leaving behind, along with the work site, their tools and arms. The waterfront villas were empty, everything within the casemates’ firing range had been blown up, the beaches were mined, and the artificers were busy here and there rendering access to the sea.

The clearest feeling was still one of absence; the immense beach of La Baule was deserted, there were less than a dozen of us on the loop of blond sand, not a vehicle was to be seen on the streets; this had been a frontier that an army had just abandoned, and the meaning of this oceanic immensity was intertwined with this aspect of the deserted battlefield.

But let us get back to the sequences of my vision. The rail car I was on, and in which I had been imagining the sea, was moving slowly through the Brière plains. The weather was superb and the sky over the low ground was starting, minute by minute, to shine. This well-known brilliance of the atmosphere approaching the great reflector was totally new; the transparency I was so sensitive to was greater as the ocean got closer, up to that precise moment when a line as even as a brushstroke crossed the horizon : an almost glaucous gray-green line, but one that was extending out to the limits of the horizon. It’s color was disappointing, compared to the sky’s luminescence, but the expanse of the oceanic horizon was truly surprising: could such a vast space be void of the slightest clutter? Here was the real surprise: in length, breadth, and depth the oceanic landscape had been wiped clean. Even the sky was as divided up by clouds, but the sea seemed empty in contrast. From such a distance there was no way of determining anything like foam movement. My loss of bearings was proof that I had entered a new element; the sea had become a desert, and the August heat made that all the more evident – this was a white-hot space in which sun and ocean had become a magnifying glass scorching away every relief and contrast. Trees, pines, etched-out dark spots; the square in front of the station was at once white and void – that particular emptiness you feel in recently abandoned places. It was high noon, and the luminous verticality and liquid horizontality composed a surprising climate. Advancing in the midst of houses with gaping windows, I was anxious to set foot on my first beach. As I approached Ocean Boulevard, the water level began to rise between the pines and the villas; the ocean was getting larger, taking up more and more space in my angle of vision. Finally, while crossing the avenue parallel to the shore, the earth line seemed to have plunged into the undertow, leaving everything smooth, no waves and little noise. Yet another element was here before me: the hydrosphere.

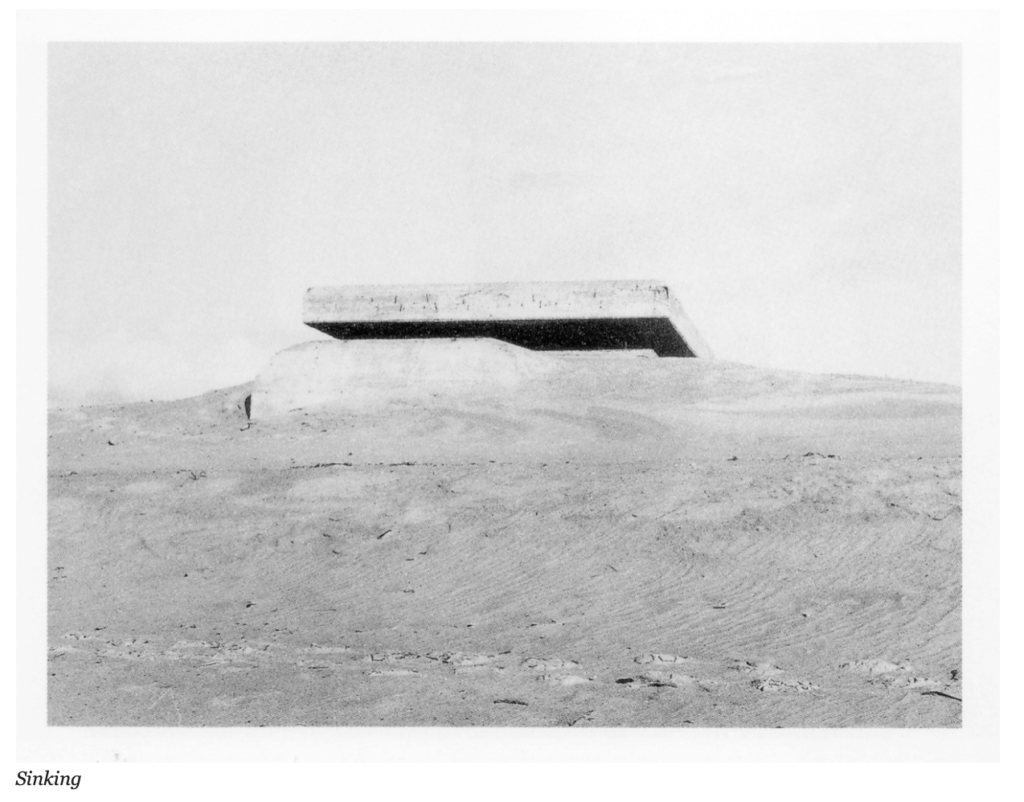

When calling to mind the reasons that made the bunkers so appealing to me almost twenty years ago, I see it clearly now as a case of intuition and also as a convergence between the reality of the structure and the fact of its implantation alongside the ocean: a convergence between my awareness of spatial phenomena – the strong pull of the shores – and their being the locus of the works of the “Atlantic Wall” (Atlantikwall) facing the open sea, facing out into the void. (Bunker Archaeology, Paul Virilio, 1975)

As light from distant stars is deflected by an imposing mass, favouring the illusion of gravitational optics, our perception of depth might well be a kind of visual plunge, comparable to the fall of bodies in the law of universal gravitation. If so, the perspective of the real space of the Quattrocentro would have been early scientific evidence of this. In fact, from the moment in history, optics becomes kinematic. Galileo was to supply proof of this in the face of all opposition. With the Renaissance perspectivists, we ‘fall’ into the volume of the visible spectacle as though by the force of gravity; literally the world opens up before us. Much later, physiologists will discover that the faster you move from one place to another, the further ahead your eyes adapt. From then on, the old ‘vanishing lines vertigo’ is coupled with the projection involved in focusing one’s eyes. To illustrate this sudden magnification of vision as a result of an increase in speed, here is the tale of a parachutists, a free fall specialist:

‘Eyeballing consists in visually assessing the distance between you and the ground the whole time you are falling. You evaluate your height and work out the exact moment you need to open your parachute based on a dynamic visual impression. When you are flying in a plane at an altitude of 600 metres, you don’t have anything like the visual impression you have when you clear this altitude in a high-speed vertical fall. When you are at 2,000 metres, you can’t see the ground approaching. But when you reach the 800 to 600 metre mark, you start to see it ‘coming’. The sensation becomes scary pretty quickly because of ground rush, the ground rushing up at you. The apparent diameter of objects increases faster and faster and you suddenly have the feeling you are not seeing them getting closer but seeing them move apart suddenly, as though the ground were splitting open.

This account is invaluable as it illustrates in a truly gravitational way the dizziness induced by perspective, its apparent weightiness. To this ‘eyeballer’, perspective geometry appears for what it has never ceased to be: a headlong rush of perception in which the very rapidity of free fall reveals the fractal nature of vision that results from high-speed eye adaptation. In this experience, at a certain distance, at a certain moment, the ground no longer approaches, but parts and splits open, going suddenly from a ‘whole’ dimension with no receding lines, to a ‘fractional’ dimension in which the visible spectacle gapes open. The horizon of visibility of the ‘faller’ prior to being smashed to smithereens depends essentially on the speed at which his eyes adapt, focusing and an imperceptible time freeze depending on the mass of his body itself. The path’s being defines the subject’s perception through the object’s mass. The falling body suddenly becomes the body of the fall. (Open Sky, Paul Virilio, 1997).

notes to self