pre

October 2018

November 2018

January 2018

February 2018

BUILD A MODEL TO TAKE OUT THERE // SPINNING SPHERES – FREI OTTO

What media/architectural techniques could I use

FA’s evidence files, taking the shape of models, drawings, maps, web-based interactive cartographies, films, and animations have also been exhibited in leading cultural and art institutions

CLUSTERS

COSMICITY

Spatial interruptions

Different collectives / associations /

March 2018

Waiting for Gobordot

anaklia

24.06.2018

24.06 Leaving London Luton, the airport was evacuated, paced through security / made it to flight / apprehension

25.06 Touchdown in Kutaisi. Picked up by man, loopy driver, almost kills dog. Temi Hostel. Dato and small cat. Visit Stalin’s bathhouse, gorged on khachapuri and salty naan.

26.06 Marshtrutka to Anaklia for 7 Georgian laris / arrived in Anaklia and met Evelina at Cafa Nata run by Chito. Evelina was sat when I arrived and she quickly launched into a colloquial Georgian conversation – abrupt back and forth, wit curling off of the harsh Caucasus Tonge —> Chito plated up soon after and we began eating and talking about all things logistical / infrastructural. Chito’s son-in-law – a stock-barrel of a man and the local police chief arrived soon afterwards with two officers in tail. Their hesitation or rather confusion to my presence was equally met with stalling, I imagine the Chief of Police in a town of 600 is an apex, we shake hands soon after, his stockjug shoulders leaning in to shake mine. Aside the Police Chief, three local contractors, builders I am unsure, drink wine out of large plastic holders. We sit for a long afternoon lunch before saying our thanks. – madlobar, one of many misfired pronunciations are made – we leave Chitos crossing to the White House of Anaklia, the hotel is still undergoing work when we arrive and are greeted animatedly by the owner. Evelina knows her, they exchange a backvolley of words, she takes us proudly up the stairs of the hotel, the rooms are simple, three beds, some two, at the top level she shows us her room, staring proudly out at Anaklia’s sole road protruding into the Black Sea. That evening the Jeep arrives. Staying above the police cheif. The key locked in the car, the local [. ] saving our skin. Hammer wedged into the door, metal hook hooking.

Place as a constellation of social relations.

27.06

Duskball Caucasus. We left Anaklia, this place will one day throughput corridors / for now it is of hotels growingly in numbers. 18 made millionaires…dispossession to foreign, building debt relations with the local banks..TBC Bank Head also Head honcho of Port.

A Structural Foam —> tracing the spherical edges of worlds opening their bodies to the dance.

The mannakinmen lost in the ether of those days. I will go back.

Photographs of then.

27.06

Duskball Caucasus, they play as the sun falls into the sloped head, look at the shadow, falling on this place. I remember long nights, kicking a ball as the shadows of a quad fell open…kicking a parabola…the world cup dreams highlights of England/Belgium. We beat Colombia two nights prior, sat on the Caspian. I couldn’t watch the Pickford moment..one giant hand padding down, duskball Caucasus – there are a hunder duskballs unfolding all a one / I surf the wave at a distance, football is coming home – A cloud mist rolls in following the game. 27.06 – passing LPG, Borjomi 32, Alkhaltskine 80.

The road of – is it dual monopeak – the road signs seem to point the old way / an effort has been made to shade out the top of the arrow but it allays nothing, Georgian driving alloying into metallic suspension, disbelief carriees maneuvers, heads poking out sides of flagging machines, to dual carriage that once went both ways cuts across the bow of Omen Interstate / a clammed up Looshus

—> went into the dance of frenetic blind path judge, stop distance, tailgate pass, close opening to new / decision cut

Camera cuts into the Caucasian valley, slowly falling into irreducible blue.

27.06 16:33:53 – river pass to the apartment block rises above a river of green / behind the Caucasuses lie…I am sitting to the right in backseat as we drive eastward toward Tbilisi. This place must be south, the apartment rises again, touching the Silhouette of the Caucasus brethren before falling away.

We pass the Mashukeh man.

I told myself I would capture as many photographs as I could… a photograph of a photograph… photographs…the imprisonments of light, surface, perspective, colour

JUST AS YOU ONLY TRACE THE POLITICAL IN A BRUSHSTROKE, the small tiny detail…to a larger thing …. Just like tracing a brushstoke in an image.

Baku – Giorgio Gappi chapter in Logistical Asia // an important point about the Silk Road revival is that it works on the basis that all countries improve their infrastructure and want to harmonise policies across trade, customs and transit procedures. If Georgia doesn’t have good Ports and Roads, then we cannot reach our potential / BAKU 1920, Congress of the People of the East – anticolonial movements.

“Guys, what are you doing here?” (Giorgio Gaganidze, TSU, 13th Floor, Friday, understandable.

27 January 2019

October 2019

it was the earliest image I named, moonlines, and now I have found some arrival, intelligence. Soul Dyadism, you reach a point, where things flow naturally…

duskball caucasus … what was at stake… what would be lost, the nuclear hum.. you don’t notice it…

our culture’s divided soul

Howard Teich

We live in a culture that divides us from each other and within our selves. The two primary modes of thinking that constitute human con- sciousness, one intuitive, sensual, and emotional, the other analytical, focused, and goal oriented, are complementary. Both modes, which have been called respectively, lunar and solar, work best in tandem, through an internal collaboration that creates balance in thought, perception, and emotion. Yet, in our divided culture, solar consciousness has become so dominant and the lunar so diminished, that we have lost this balance. We think without feeling and yet underneath our logical postures, we are driven by passions that we never examine.

This destructive habit of mind we have inherited shares a history with both terrorism and the war on terror. The events of September 11, 2001, set in motion the latest phase of an epic conflict that began thousands of years ago with the development of three religions: Juda- ism, Christianity, and Islam. All three of these religions grew out of cultures that originally worshipped a variety of gods and goddesses. But the move toward monotheism, a defining characteristic of all these traditions today, necessitated the repression of many deities, along with the various values they represented; a diverse pantheon of deities, both solar and lunar, was replaced by a single solar god with one set of values.

At first glance this theological history may appear irrelevant to Amer- ican actions. While Osama bin Laden and his followers are describing the war on terrorism as a war against infidels and calling their own acts of violence a “holy war,” we deny that we are conducting a religious war. We pride ourselves on the separation of church and state.

However, though it is undeniable, on a conscious level, that the stated motivations of our efforts against terrorism are secular, concealed within this rhetoric, less secular motivations can be detected, even in the offi- cial language of the government. In remarks made after the bombing of the World Trade Center, President Bush used the words “evil” and “cru- sade” to describe, respectively, terrorist acts and our response. Although the Bush government had been at pains to distinguish between the Is- lamic religion and terrorism, the use of the word “evil” has continued to work at cross purposes to this policy, unconsciously expressing a co- vertly religious judgment.

Regardless of competing claims, all three religions share in Abra- ham a figure, who, as we shall see, represents a set of desires and de- signs that in preceding cultures have been connected to gods and god- desses associated with the sun, and in turn with the solar aspect of human consciousness.

In the pantheons that once existed in religions throughout the world, a range of solar deities can almost always be found whose attributes reflect a particular set of human characteristics allied with power—strength, protectiveness, and power—with the ability to assert control, and corre- spondingly, the clarity of mind that comes from analytical thought.

But in these pantheons, these deities were matched and balanced by another group associated with the moon, consisting of both gods and god- desses, whose attributes reflect the lunar side of consciousness. This aspect of the human psyche contains the attributes that enable cooperation and relationship, including emotional and sensual awareness and empathy.

Solar values are not in themselves destructive. But whether in service to a private life or a society, solar values require balance from lunar val- ues. To fulfill any goal, the ability to connect with others or a larger web of existence is crucial. Moreover, the rejected lunar aspect of conscious- ness does not disappear but is repressed, only to reappear as a negative projection onto other peoples. In a historical context between nations and peoples, demonization is often reciprocal. While Islam is often de- monized from a Judeo-Christian perspective, Westerners, Jews, and Christians have been demonized for decades by extreme Muslim sects.

with the shift from polytheism to monotheism, the lunar vi- sion of reality, a way of knowing bound to community and the earthly experience of life, one that valued relatedness and sensual knowledge, was sacrificed. This vision of the universe as an organic and sacred whole was replaced by fragmentation; now humanity was opposed to nature, intellect to emotion, spirit to matter; tribe was set against tribe, whole peoples set in conflict.

Over the next thousand years as the solar side of the psyche became more and more dominant, the lunar side became a secondary phenom- enon, habitually projected by these three religions, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, onto those described as “other,” who were often demon- ized. Today, our image of terrorists evokes this shadow land of lunar consciousness.

Yet to say that Western culture projects the lunar onto Ishmael is not to imply that terrorists from the Middle East are lunar. Despite the fact that we project the lunar onto them, terrorist organizations are as solar- dominated, if not more so, as the American and European governments that battle them. In 1998, in a clear example of solar thinking, Osama bin Laden declared that his jihad was a “holy war” against the United States because the “crimes and sins committed by the Americans are a clear declaration of war on God, his messenger and Muslims.”

The word jihad, which means “striving,” appears frequently in the Qu’ran in the phrase “striving in the path of God.” In one interpretation of the phrase it signifies an internal struggle for enlightenment, an inter- pretation that would signify the more lunar process of reflection. But the same phrase has been used both in the past and recently by fundamental- ists to mean armed struggle for the advancement of Muslim power. It was appropriated by bin Laden, who erased reflective consciousness from the meaning of jihad.

The same process of excising lunar consciousness has occurred in the West. To banish Ishmael is to banish our sense of collective identity and relationship to the whole of existence.

The rejection of lunar values in Western traditions however is not confined to the story of Abraham. Though Christianity began with a revival of lunar values, lunar consciousness was soon diminished in this religion, too. Despite the fact that Christ is known as the Prince of Peace, Christianity also sacrificed the clear lunar teachings of Christ for another set of values. A predisposition to war gained early ascendancy within Christianity during the reign of the Roman emperor Constantine after his conversion in 312 C.E. Because he attributed a major military victory to the power of Christ, he committed himself to the Christian faith. As the official religion of an empire, rather than advocating peace, Christianity adapted itself to the ambitions of empire, a task made eas- ier by the dualism between spirit and matter, emotion and intellect, solar and lunar values. Our culture has been deeply imprinted with these histories. But we do not have to repeat them. If we reclaim our lunar resources not only can we avoid self-destruction, but we will be better able to address the very real threat that terrorists pose today.

From an exclusive solar perspective we are not able to distinguish between defense and aggression, nor can we explore the full range of dip- lomatic solutions. Through the prominence of military values and the idealization of the warrior, which takes place during warfare, violence increases solar aggression. To resolve this conflict in other than militaris- tic ways will require all of us to cultivate the lunar values of compassion and relationship as part of our response to terrorism.

Yet as radical as this shift may seem, all lunar modes of conscious- ness, including the emotional understanding and empathy needed for diplomacy, belong to a primal way of knowing and being that developed thousands of years ago as survival skills, long before language and other cognitive abilities had fully evolved.

This knowledge still exists in us, even if only on a cellular level. Lack- ing access to the lunar we are like plants without roots into the earth that shrivel up. It is not just our current crisis that hangs in the balance. We need to reclaim the full dimensionality of being if we are ever to have lasting peace, both inner and outer, and live harmoniously with the earth that sustains us.

“Religion and democracy in this country . . . have mutually strengthened each other. . . . Here, as perhaps nowhere else in the world, the fundamental unity of Christianity and freedom has been demonstrated.” Besides providing the foundation for American civic life, Truman believed that religion offered the human race its only hope. “Religion alone has the answer for humanity’s twentieth century cry of despair, ‘What must I do to be saved?’ In this time of grave anxiety the voice of science unites with the voice of religion to affirm that the words of Jesus, ‘Do good to them that hate you,’ are not only the words of Christian idealism but also the command of democratic realism.”11 Concepts previously considered at odds with each other, such as science and religion, or idealism and realism, were now united, Truman declared, in affirming a common hope. Humanity faced a new era, in which old disputes had been resolved and unprecedented challenges awaited.

Curiously, Truman initially pointed not to competing ideologies but to the nuclear age itself as the harbinger of change. “The atomic bomb destroyed selfish nationalism and the last defense of isolationism more completely than it razed an enemy city. It ended one age and began another: the new and unpredictable age of the soul.”12 He ascribed an almost eschatological significance to nuclear weaponry. It had not merely revolutionized diplomacy and warfare; it had ushered in a new spiritual reality. The American people now needed to look clearly at the world, and peer into their own soul, and resolve how they would live. Parochial withdrawal from international affairs was not an option, Truman insisted, nor was callow sentimentality. The new reality demanded an America that would eschew its insecurities and confront its challenges.

The state of this new world soon began to take shape, and it was grim to behold. Truman’s cautious concern in 1946 gave way to a firm resolve in1947 to counter the emerging communist threat. The Soviet Union appeared to Truman as an expansionist menace, threatening not only countries on its borders or even the security of the United States, but also the very notion of freedom and the existence of those who cherished it. In response came his announcement on March 12, 1947 of what became known as the Truman Doctrine: “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.”

In a June 4, 1950, commencement address at Vanderbilt University, Dulles proclaimed that “the big difference, indeed the only vital difference” between the two realms “relates to ideas, not things. . . . Our people, as a whole, believe in a spiritual world, with human beings who have souls and who have their origin and destiny in God. As put in the Declaration of Independence, all men are endowed by the Creator with certain unalienable rights.” Drawing a stark ideological contrast, Dulles declared that “Russia, on the other hand, is run by communists who deny the existence of God, who believe in a material world where human beings are without souls and without rights, except as government chooses to allow them.”16

Pythagoras, when he was asked what time was, answered that it was the soul of this world.

—Plutarch, Platonic Questions

The Size and Speed of “Now”

Yet “now” also extends beyond our planet. It stretches almost to the moon, which is 1.3 seconds away at the speed of light. But when things get farther away—say, the ninety-three-million-mile distance to the sun—the simultaneous instant ends. How is this possible? We know that light coming from the sun takes eight minutes to get here, so com- mon sense would tell us that that we can easily account for that differ- ence in time, that delay, simply by compensating for it. We can imagine, for example, that the sun could be erupting with a huge solar flare at this very moment, and although it would take eight minutes for us to see the flare, we intuitively think there is a sort of God’s-eye view of simultaneity. We know the flare is happening “now”; it’s just that we won’t see it right away.

Real Time and Time Lags

In a media world of unreal time—where daily talk shows and the eve- ning news are pre-taped, where Star Trek rubs shoulders with docu- mentary footage from the First World War—broadcasts that are genu- inely live have an instant cachet. The Olympics, live sports programs, unfolding disasters, car chases, all draw huge audiences. But a few years ago, another, more complicated kind of live broadcast arose—“real time”—and two-way video conferencing was one of the first exam- ples. Video conferencing purported to take place “in real time” because a computer processed the signals so quickly that there was no delay between sender and receiver, something that had not been possible earlier. The result was a two-way visual phone conversation. Nothing radical in that, or so it seemed. But the fact that a computer was work- ing furiously to translate, send and then untranslate the digital signals subtended the whole process. It wasn’t like video surveillance, which might also be said to take place in real time, but which merely reflects reality; there is no processing of the signal. Real time is synonymous with a kind of hyper-time, where electronic circuits race furiously just

to stay in the present moment. It is as if the higher the price paid to be here and now, the more privileged the present moment.

The term “real time” was readily adopted and assigned to all sorts of things—for instance, the stock market crawlers that tick away at the bottom of your screen, or the “real-time four-wheel-drive” feature of some sport/utility vehicles (SUVs), which automatically switches from two- to four-wheel drive when you go off-road. Real time means that we are moving so fast we have caught up to the present—which waits for no one, save the fastest.

So “real time” is a commodity, something you can buy if you have enough money, unlike those who are marooned in what must be “unreal time,” where computers aren’t fast enough and cars don’t have automatic asymmetrical 4WD. (In one sense, “real time” is reminiscent

of “quality time,” those hours that busy people snatch between appoint- ments and jobs to be with their children.) On the other hand, tele- vision’s version of “real time” is trickier, particularly in live broadcasts. Sometimes people do or say things that networks would prefer they didn’t, and so broadcasts have a built-in time delay of several seconds that allows producers to hit a “dump” button and delete the offending sequence. We don’t notice a built-in time lag the way we notice the delay of an audio feed on a live television report from halfway around the world, where reporters blankly wait for the anchor’s next question. Yet there are other built-in time lags—one military and the other bio- logical—that are almost completely invisible.

In the command-and-control situation room of modern battle- ships, a wall-mounted screen shows real-time positions of enemy boats, planes and missiles. During the Falkland Islands war in 1982, H.M.S. Sheffield’s radar defence shield was down temporarily while a satellite phone call was made back to Fleet Headquarters in England.

When the radar screen came back online, it showed two enemy planes,

thirty-three kilometres away—much too close for comfort, and, as it turned out, too late for response. Exocet guided missiles were already skimming towards H.M.S. Sheffield, just above the waves, at the speed of sound. There was not enough time to launch electronic counter- measures. All the officers could do was helplessly watch as the incom- ing blips tracked closer and closer.

But there was a further wrinkle. Because missiles and jets move quickly, most situation screens for both land and naval battle zones have built into them a computerized time delay of slightly more than

0.2 seconds. This delay counteracts the minimum human reaction time. The delay had been built into the command-and-control screen of Sheffield, which meant that—like a sinister video game—the officers saw the missile hit the target on the screen a moment before the ship

itself exploded into flame.

Our 0.2-second reaction time is itself affected by a deeper neuro-

logical phenomenon, one that some neurologists believe is proof of an immaterial soul. A few decades ago, a neurophysiologist by the name of Benjamin Libet discovered a perplexing paradox about the nervous system and the brain. During brain operations, when patients were conscious and parts of their cortex were exposed, Libet conducted experiments on how long it took for a pain impulse to reach the cortex, and then how long it took for the patient to report the pain. With the patient’s consent he would prick the skin and measure when the incoming impulses hit the part of the brain that represented that area.

A pain impulse takes only 15/1,000 of a second to reach the cortex, but the brain takes half a second to translate that signal into conscious awareness. You can see the spikes on an oscillograph wired directly into the brain; it’s hard science. Yet all patients reported the sensation after only 0.2 seconds had passed. Libet was stumped. How could you be consciously aware of something before your brain had delivered the

information to you? He hypothesized that there must be some sort of perceptual mechanism that antedated the signal in time. But what was this “perceptual mechanism”? The question became a famous bone of contention among neurologists, and continues to be so up to the present day. How is it possible for the brain to “jump time”?

The famous neurologist John C. Eccles said he had the answer. He believed that Libet’s “perceptual mechanism” was evidence of an imma- terial, self-conscious mind, one that scanned active modules in the brain, getting the jump on the slower processing of the cortex. Other brain processes, he noted, indicated the presence of something that wasn’t the product of neurons and electrical-chemical impulses. So in his opinion, the evidence for an immaterial mind was just too over- whelming. In a conversation he had with the philosopher Karl Popper in 1974, he said that he was “constrained to believe there is what we might call a supernatural origin of my unique self-conscious mind.”

The mind time-travels. Continuously, every moment we are alive, our consciousness is time-lapsed by a tiny, mysterious, 0.2-second journey back in time. Our ability to be in the present moment is more—much more—than it seems to be.

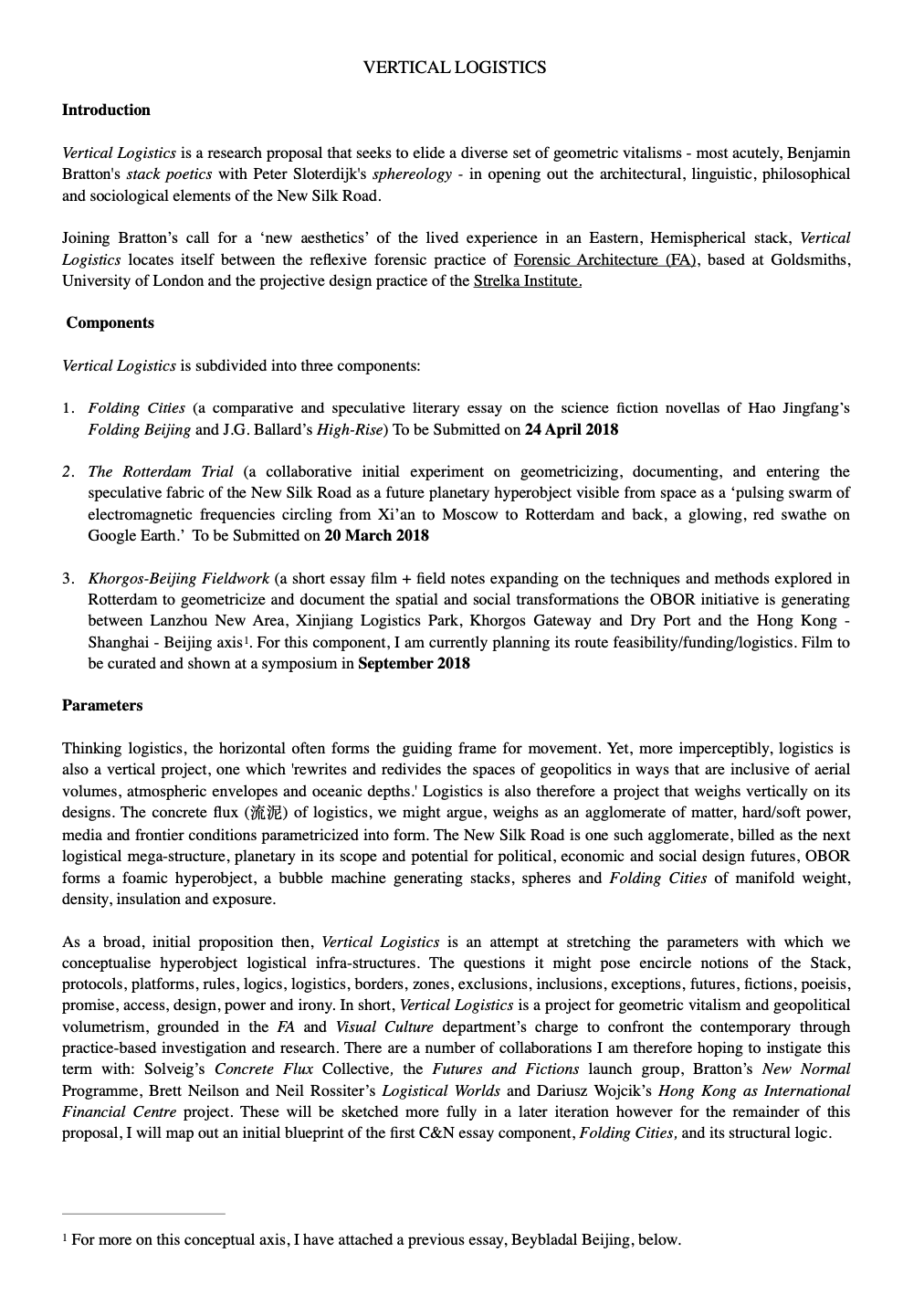

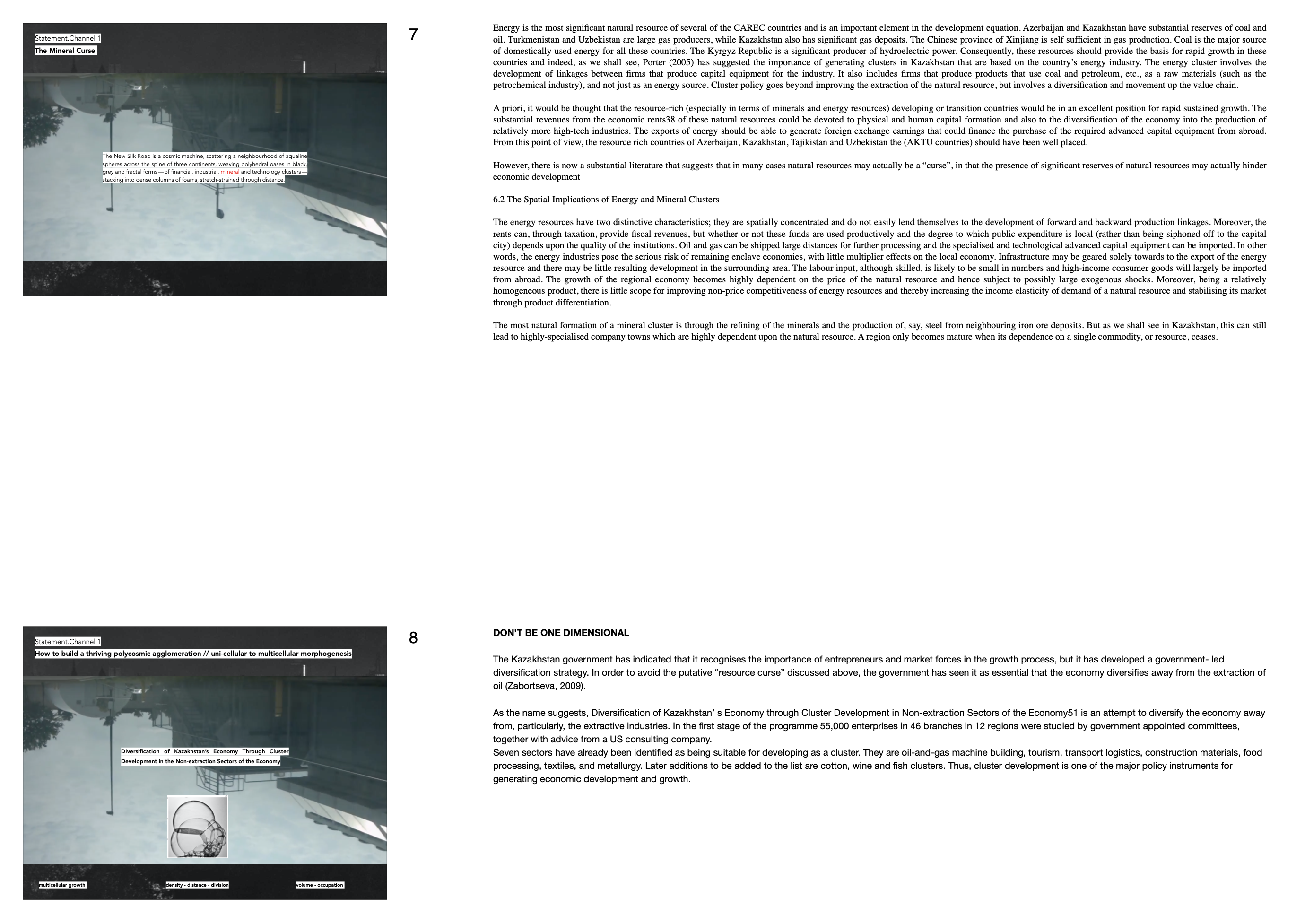

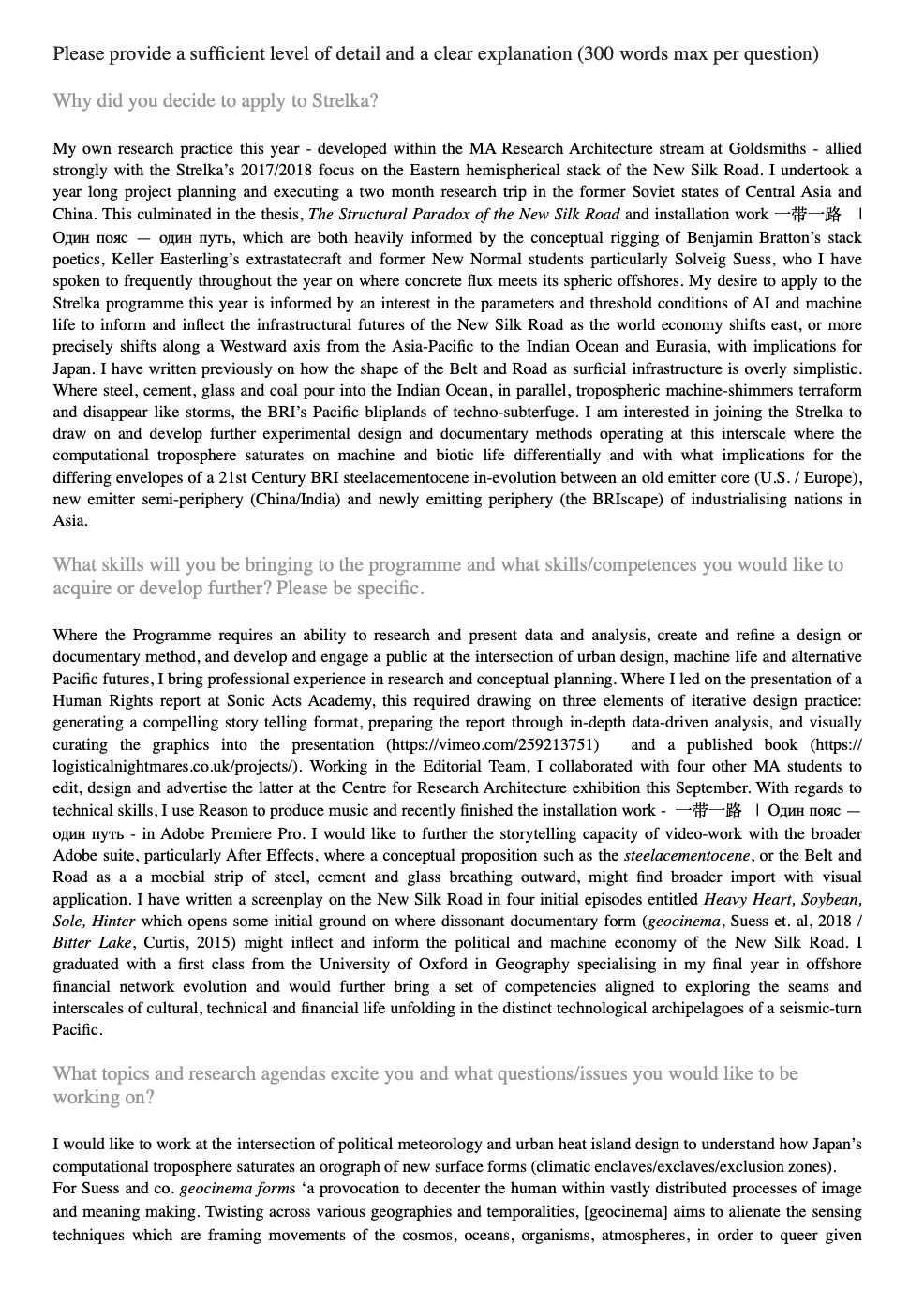

Date | Departure | Arrival | Distance | Notes |

22/07/18 | Urumqi | Dunhuang | 987km | K4931 train, 14.5 hours (overnight), 7pm to 10am for soft sleeper |

23/07/18 | Dunhuang | Zhangye | 594km | 2/3 trains a day, 7.5hour journey |

24/07/18 | Zhangye | Lanzhou | 503km | Frequent trains, 3hour journey |

26/07/18 | Lanzhou | Xi’an | 626km | Frequent trains. 2.5 hour journey |

28/07/18 | Xi’an | Chengdu | 510km | Frequent trains |

30/07/18 | Chengdu | Chongqing | 681km | Frequent, fastest under 5 hours |

31/07/18 | Chonqing | Yiwu | 1551km | Between 10-35 hours. Overnight or whole day. |

01/08/2018 | Yiwu | Shanghai | 284km | Very frequent, fastest 90 minutes |