The Story pauses for AQ and Robert and the docklands and picks up following Pearl Harbor, with J.F Jack Fletcher entering into the Port, witnessing the devastation… It cuts back to John Ford, the filmmaker, on his yacht on the coast of Baja California and Mexico in 1939. The three dimensions of the NSS a constant motif, the way the air attack transformed the optics of war, a lesion, trauma is not languid but an engine, blinding sunlight in the lens, A constant motif is John Ford, eyepatched, filming in the Pacific, the Talmudic refinement of depth, solar angles, at Midway a bomb exploding nearby, siniy-goluboy, resonance, and a paranoiac sense that the time is bleeding toward something, something indescribable, two lines diverge…

Think of two parallel lines, he said. One is the life of Pearl Harbor. One is conspiracy to kill the Hiroshimans. What bridges the space between them? What makes a connection inevitable? There is a third line. It comes out of dreams, visions, inhibitions, prayers, out of the deepest levels of the self. It’s not generated by cause and effect like the other two lines. It’s a line that cuts across causality, cuts across time. It has no history that we can recognise or understand. But it forces a connection. It puts a man on the path of his destiny.

What was the plot that tied the two together, wrote them in, two lines diverge, DeLillo wrote, two lines diverge Think of two parallel lines, he said. One is the life of Lee H. Oswald. One is conspiracy to kill the president. What bridges the space between them? What makes a connection inevitable? There is a third line. It comes out of dreams, visions, inhibitions, prayers, out of the deepest levels of the self. It’s not generated by cause and effect like the other two lines. It’s a line that cuts across causality, cuts across time. It has no history that we can recognise or understand. But it forces a connection. It puts a man on the path of his destiny. a sense-making of history centred on the role of the irrational and its instrument, the man who, as Delillo told Ann Arensberg, ‘stepped outside history and let the forces of destiny move him where they would – non-historical forces like dreams, coincidences, intuitions, the alignment of the heavenly bodies, all these things. / it is the workings of dreams, coincidence, astrology – all that lies outside systems of historical logic. Only the ‘language of the night sky’ can express the truth behind Oswald’s act, but it is an astrological ‘truth at the edge of human affairs’.

Damn you, damn sky, damn planes, blitzer against the dream, damn god damn the fucking light gone now, why history’s not a line moving up, its that friction, that fission – that heavy elemental collision of ideologies, pay packets, hopes, dreams, loss, fuck the plan can’t work here tidal moon come ashot feel the rays reflective solarine, why how when did we meet do I know you, took to the beach with you, deliverance with you, from horror, from erewhon, from the beat path, spunout, spunin, nuclear sunsets – rigged – why is my life a string of nuclear sunsets, why is my life a string of nuclear sunsets, wipe away the horizon, loess the cane, no good can come from the white man’s rain, haole, Howl, Ginsberglike against the wind against the noiselight, against the thousands young bloatfloat weighing steel below floor, bathymetric brothers, scrawled into the secret they’ll never know the kids they’ll never throw ball against the Honolulu nightlights, all aslipstream to the byeshadow of the blow, the firelight lesion, he saw the port ablow and started talking flowers, she was riding a car, Otto was hanging linen, industrial espionaged linen, he’d be found, they’d all be found, paranoiac siniy and goluboy, siniy and goluboy – the remnacane of the primary lesion that came out of that ice blue sky, the martial law, blackout, information closure, boats, planes, anti-Japanese, mainland lockups, second-class, the wait, the weight, five year plan paned Kolmya, he in a Siberian camp, sweating out love, loss, nova-cane, cane, sugarbled-dry docks requisitioned war, arrival.

J.F.

The J.F Pacific Dyad Left: J.F John Ford, Right: J.F Jack Fletcher. See Searching for John Ford: A Life (Joseph McBride, 2000); See Black Shoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway and Guadalcanal (John B. Lundstrom, 2006).

Black Shoe Carrier Admiral, Read Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher || HE WAS AT ANNAPOLIS, TWO LINES DIVERGE… WHEN JOHN DIDN’T GET INTO ANNAPOLIS…. Almost like the two lives were mirrorlines of some god with an experimental interest in the human soul, and the divergence of the life cord… John became John Ford…Jack became read admiral Jack… von Braun and his soviet counterpart… so many mirrorlives…

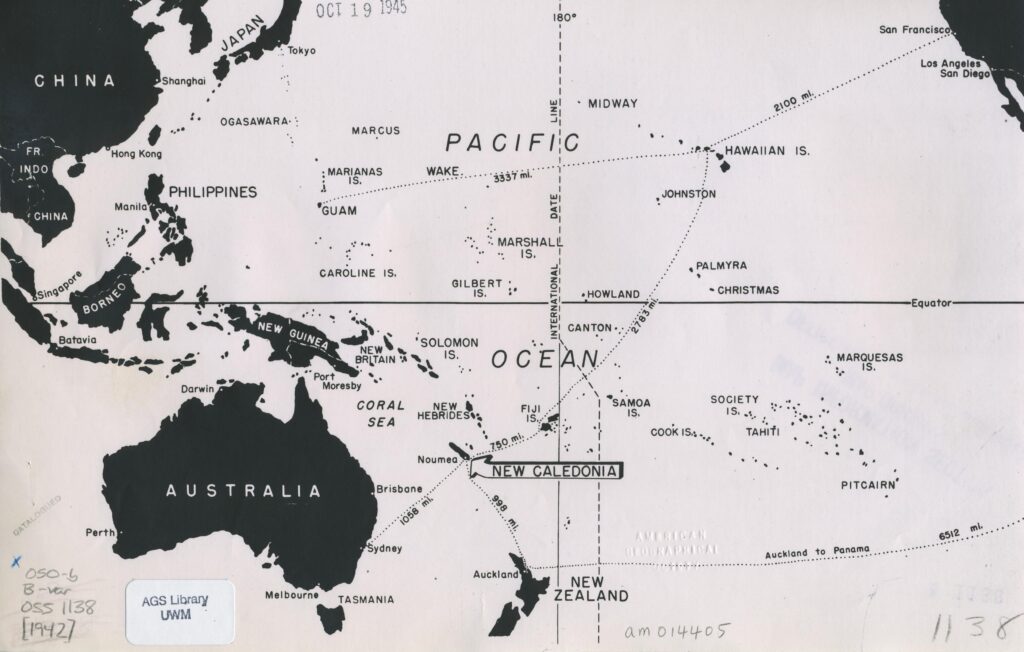

John Ford IT’S ALL ABOUT CUBIST PACIFIC…. Cubist in longitude … cubist in latitude…. Memory is cubist… perspectival…. shimmershift…. Sphera…. John Ford on his yacht in Baja California… in Mexico…. Maybe for Beijing you will look at the life of the rocket man Thread of the Silkworm…. It’s Underworld… It’s Americana… but its where the American frontier is Pacific…. Its oceanic…. Its the fracturing deep of the psyche-soul out in the ocean…. It was always in the ocean…. The primal return….

The dyad the breathing couplet, history not as a line but as the byeshadows of resonance pivots, thrown from one into the next, Dec 7 1941, a lesion, and trauma is not languid, trauma is an engine etched into the soul…. The military souls saw the island for what it was, one great scream across the Pacific, a means, a machine, one huge hulking mass ejecta screaming in the face of Dear Joe, they were under the machine, but did they know what conspiracies, what gathering dust line and sight, what recordings, and hearings and silent charges were being met as they walked, breathed fought the line, the fission line, and the day with your name written on it, coming closer, coming like the weight of water that collapses over you, and your heart has three souls, and you’re running on deep blue subconscious shock throughout the whole thing, the reds and lighs, ant blurring signatures of celestial deliverance, of fuel and blub and

Mechanisation act, the dockmen becoming fuselage to the machines, redundifying – the soul was giving up the wake… we’re losing Robert, we’re fucking losing it, this island treated like second class fucking peoples, I couldn’t capture the times, I couldn’t capture the times, yawning, distant, headspace I didn’t know moments I coulldnt catch, the human serene a smear across the browbeat horizon, the rainy days picking cane in the fields, mother with broken feet, and Robert coming across the Pacific on his steamer, the depth of the soulfreight, you could never know

The Rashomon Effect. The Kessler Syndrome. Writing’s two speeds, depth The war came and went and Robert came home, and Gail was born in 43, in 49, we organised longshore strikes, and Gail sat on the shoulders of Robert, The Honolulu Advertiser smeared Jack and the ILWU and us: 1950, it was not automatic style of writing, it was an explosive style it was penning and penning and penning, and release, abruption, depth and blow, depth and blow, the psyche’s model, depth and blow, the way they hulked cargo into the bowels of the passing ships, and their shoulder sockets merged with the rhythm of the steamers and they were bound to the San Franciscan nightlights like any other god damn moth-balled fanatic finding god in the steelworks – organising, organising, if only they knew what Stalin was doing in Kolmya, deep cold Siberia, the conspiracy of a shelf a deep shelf

The 1950s came and Eisenhower went and the psyche became a frontier, the psyche became a frontier, just as the ocean became a frontier, and space became a frontier, it was a re-dimensionalising of the mind as world, as this corrugation of steel and depth and speed, and missile, missile paranoia, missile LSD, missiles growing, missile spotting, missiles imagining, atomic death, atomic death, atomic blows brought around you cannot contain the free spirit soaring of the U.S., and this was what some man wrote that the American frontier started east coast and drew out west but then kept going kept going after the war that the real resonance flight of the nuclear heartland was an ocean-infill boom, boom Atlantic, Pacific. All nation’s souls ran by the logic of expansion, of explosion, of resonance, of fighting to blow out across all dimensions, and that the U.S. blew out across all of them east, west, north, south, up, down, left, right, everything had a name, had a number, had a study group, had a project number, had a classification, had secrets, had names, had deaths, had

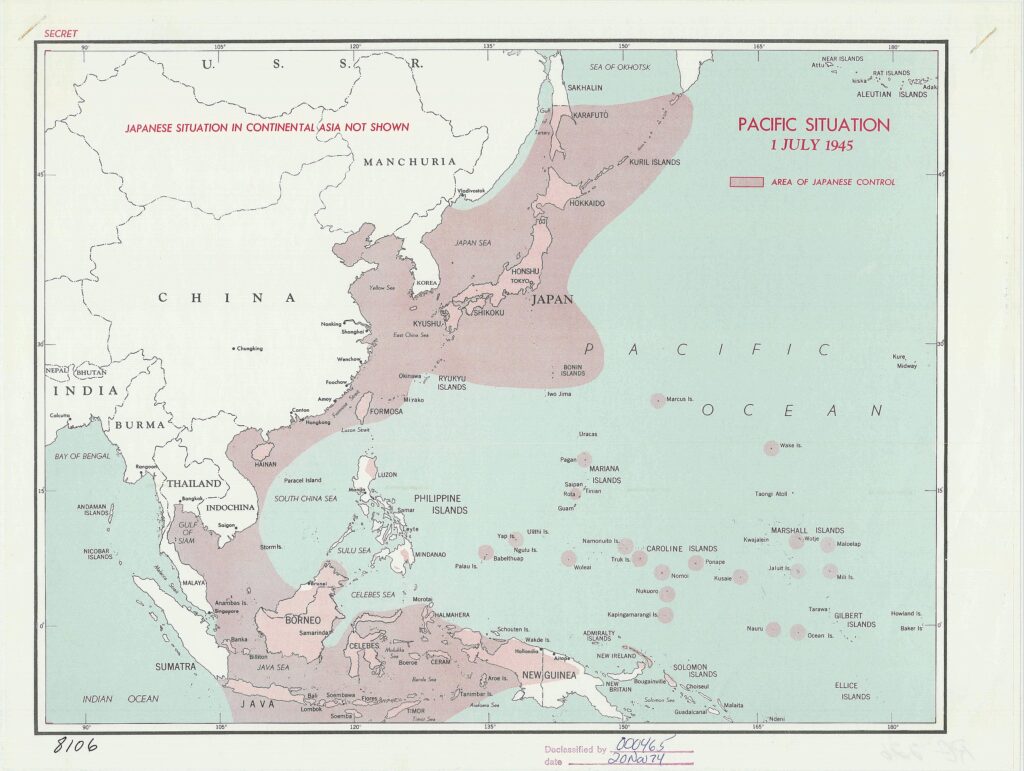

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Maps_of_World_War_II_in_the_Pacific

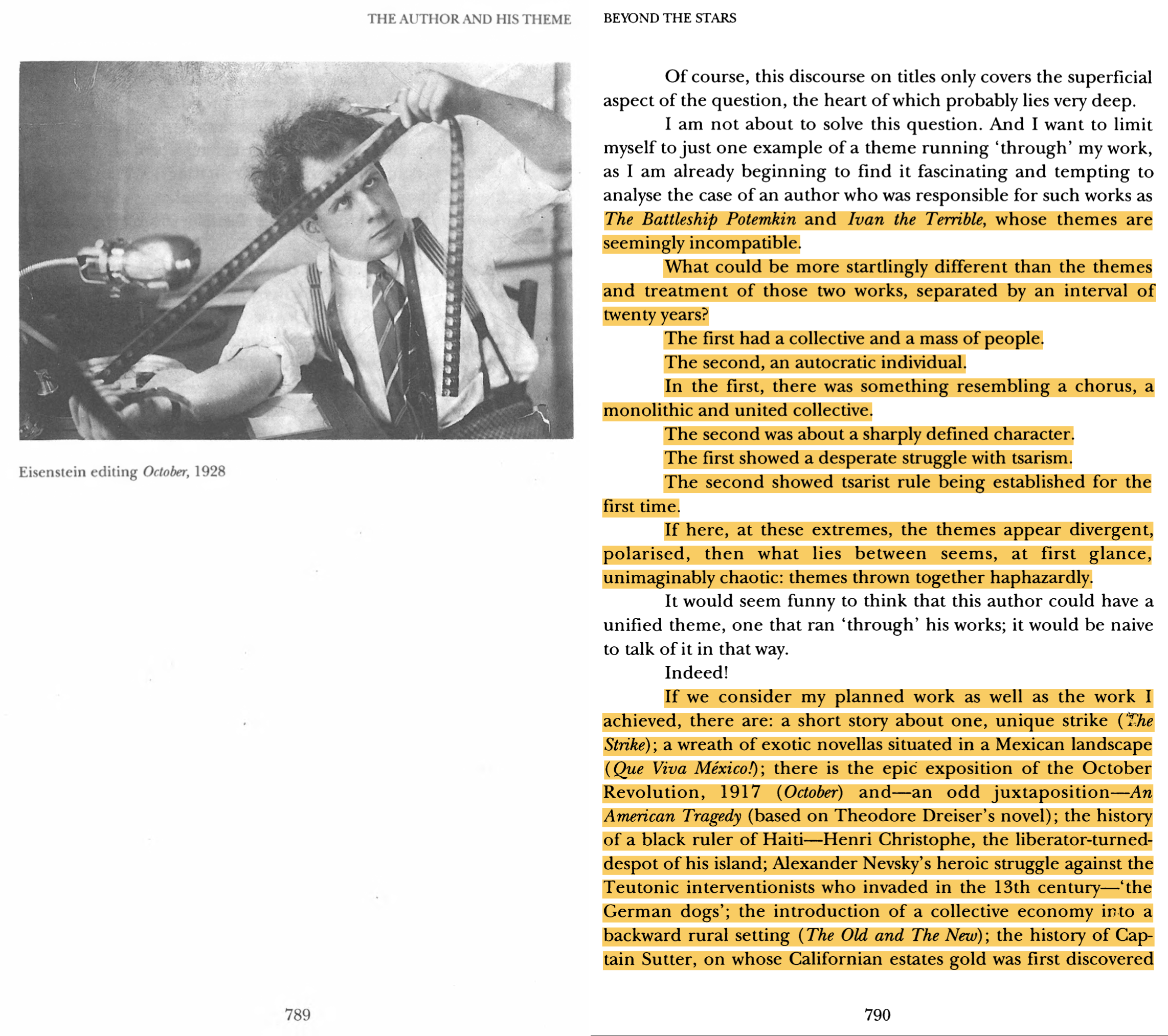

Searching for John Ford: A Life (Joseph McBride, 2000)

After being appointed a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve in September 1934, Ford made periodic cruises aboard his yacht down the coast of Baja California between 1936 and 1939, gathering information for the 11th Naval District. He reported that the crews of Japanese shrimp boats off the Mexican coast were spying and constituting “a real menace” to national defense. He said that there were Imperial Navy officers aboard the trawlers and that the Japanese were familiar with every cove and inlet of the Gulf of California. Ford was commended for his “unselfish and patriotic work. What his military records do indicate is that he performed reconnaissance missions in Mexico for the navy between 1935 and 1939, turning in secret reports and receiving citations for spying on the Japanese military pres- ence in Baja California. In contrast with Sinclair’s portrait of Ford leading a “boyish” double life inspired by a “playful sense of conspiracy,” Ford in fact was deadly serious about his spying. He fully recognized the grave implications of the rise of fascism in Germany and Japan during the 1930s and was pre- scient in his understanding that war was becoming inevitable. His inside knowledge no doubt stemmed in part from his closeness to superior officers, with whom he took pains to ingratiate himself, both for the sake of his own career interests and out of a genuine desire to be of vital service in military reconnaissance during an impending national emergency.

Among Ford’s military records is a document revealing that there was in- deed a hidden purpose behind his obtaining a navy commission. In a 1941 au- tobiographical sheet prepared for the navy, Ford wrote, “In 1931 I was asked by Admiral Frank H. Schofield, Captain Herbert Jones, and Lieutenant Com- mander Gail Morgan to prepare a course in naval photography; its uses, tacti- cal, historical, and propaganda. In 1934 I was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander in the Naval Reserve to forward this work, upon the recom- mendation of Admiral Schofield.” In a report during World War II on the for- mation in 1940 of his combat photography unit, the Field Photographic Branch of the U.S.Navy, Ford added further details, writing that he had been ordered by Captain Jones in 1934 to plan a course in “Naval and Combat Photography.” He explained that the navy wanted him to use his positions in the Naval Reserve and the film industry, as well as his experience as a yachts- man, “in studying infra-red and other supersensitive films and complementary filters as to their efficacy on sea and in the air, particularly in tropical waters.” As part of his preparation during the 1930s, Ford studied how to make training films and conducted a study of aerial and sea photography. He exag- gerated somewhat when he claimed to have “pioneered combat and sea photography” for the navy. But it was true that he “visualized the great im- portance of photography in times of peace and war,” as his commanding offi- cer, W W Waddell, wrote in February 1941. In addition to providing data for the Office of Naval Intelligence, Ford’s reconnaissance and mapping of Mex- ican waters gave him valuable practice in the art of photographic documenta- tion.

Ford’s reports were “of considerable importance/’ he was told in a 1936 let- ter of commendation from navy lieutenant commander A. A. Hopkins. “For your own personal information, [I] will state that of the six yachts who [sic] have been requested to make observations during the past two years, the Araner, its owner and commander are the only ones who have made entrance to the area you explored and who have brought back the data wanted.” The ONI noted in July 1936 that Ford had contributed “valuable and most inter- esting data on Scammon Lagoon” in Baja California. For that report, Ford spent two days with Araner captain George Goldrainer and crew members photographing and charting the area from launches. Ford wrote that while he had seen no indication of a Japanese presence, the isolated lagoon was “close enough to shipping lanes to serve as an ideal place to either stockpile supplies or to serve as a rendezvous point for submarines and sub tenders.”

Ford’s annus mirabilis of 1939 saw the release of Stagecoach, Young Mr Lincoln, and Drums Along the Mohawk, the director s informal “Americana trilogy.” By immersing himself in the American past and bringing it so stir- ringly alive in those three films, Ford reached his full-blown maturity as an artist, triumphantly finding the themes and motifs that would involve him for the remainder of his career. At a time when the world stood at the brink of war and America s role as a world power was being challenged by the demands of isolationists and inter- ventionists alike, Ford used his 1939 excursions into the American past as a means of urgently reexamining national values. Focusing on the formative years of the republic and its western expansion, he acknowledged some of the darker elements of the early American story while glossing over others that he preferred, at this point, not to examine too closely. If the patriotic messages sent forth from these films were somewhat ambivalent, since they were couched in terms of nostalgia for a brighter and now vanished past, Fords look back into American history at this turning point in his career neverthe-less was suffused with optimism about the future of his country and its demo- cratic way of life.

Its only a slight exaggeration to say that 1939 was the year John Ford dis- covered America. Not coincidentally, the end of the thirties also marked the high point of Ford’s Popular Front period. Hollywood liberals and leftists joined forces in those years, concerned about the rise of fascism in Europe and Japan, as well as about the continuing economic problems of the Great Depression. At a time when isolationism was still rampant and served to inhibit President Roo- sevelt’s foreign policy, Ford was well ahead of most other Americans in his concern about the probability of war between the democracies and the fascist powers. That concern was reflected not only in his filmmaking but also in his service in the navy reserve and his involvement in Hollywood political organizations. American leftists during the Popular Front period emphasized patriotic rhetoric as a way of finding common ground with liberals in defense of basic democratic principles. That urgent patriotic groundswell no doubt influenced Ford’s cinematic focus in his 1939 trilogy about western pioneers, Abraham Lincoln, and the Revolutionary War, as well as his decision to film John Stein- beck’s controversial 1939 protest novel about the mistreatment of migrant workers, The Grapes of Wrath. Ford’s heartfelt patriotism was expressed in symbolic, almost pop-art terms in Drums Along theMohawk, whose ending offers one of the director’s most joyously optimistic, if somewhat nai’ve, affirmations of American national unity. At the end of the Revolutionary War, when the first American flag ar- rives at a fort in New York’s Mohawk Valley, Ward Bond runs it up the flag- pole in a burst of patriotic frenzy to the tune of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” The pioneer couple Gil and Lana Martin, played by Henry Fonda (in a tri- cornered hat) and Claudette Colbert (wearing a red bonnet and a blue-and- white dress), pridefully watch the flag-raising along with a beaming black servant (Beulah Hall Jones) and a Christian Indian who salutes the flag (Chief Big Tree). All are symbolically gathered in multiracial harmony to celebrate the birth of the nation. For Ford, the fact that the new nation was “conceived in liberty” is enough for the African-American and the Native American to celebrate, even though their own personal liberty has yet to be won. Perhaps this flaw in the fabric of American democracy is obliquely acknowledged in the film’s final lines when Gil says, “Well, I reckon we better be gettin’ back to work. It’s gonna be a heap to do from now on.”

Ford’s militancy on behalf of the Screen Directors Guild helped ease him into publicly supporting more controversial political causes that reached be- yond Hollywood in the late thirties. Although he was a Catholic and the Church supported the Fascist revolt of General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republican government, Ford became an active backer of the Loyal- ist cause in the Spanish civil war, serving as one of the founders of the Mo- tion Picture Artists Committee to Aid Republican Spain, along with Dudley Nichols, Dashiell Hammett, Donald Ogden Stewart, Lester Cole, Melvyn Douglas, Fredric March, John Garfield, and others. The MPAC, which eventually grew to a membership of fifteen thousand, held rallies and benefits to raise support for Loyalist soldiers and Spanish refugees. In July 1937, novelist Ernest Hemingway came to Hollywood to seek funds for the Loyalists. Hem- ingway was guest of honor at a party held at the home of March and his wife, Florence Eldridge, both of whom had acted in Mary of Scotland. They invited Ford to their gathering, at which Hemingway screened a documentary film, The Spanish Earth, that he had helped Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens make on the battlefront. Ford was not particularly a fan of Hemingway’s work, but after spending some time talking with the writer about the fighting in Spain, he wound up donating an ambulance to the Spanish government.

Bob Ford, one of the sons of Francis Ford, was a member of the Interna- tional Brigade in Spain. From Albacete on September 30, 1937, Bob wrote his uncle Jack a thank-you letter for the ambulance. Confessing surprise that Ford was interested in their cause, Bob expressed pleasure that American liberals like his uncle were supporting the Loyalist forces. Assuring Ford that, contrary to Fascist propaganda, the brigade was not entirely made up of Communists, Bob added that Ford would be intrigued to learn that there were many former IRA men in the British battalion. Ford must have felt chastened to be responding to Bob s letter from a ranch on the Hudson River in upstate New York, near West Point, where he had gone to dry out from another alcoholic binge. “I am glad you [have] the good part of the O’Feeney blood,” Ford wrote his nephew. “Some of it is very God- damned awful—we are liars, weaklings & selfish drunkards, but there has always been a stout rebel quality in the family and a peculiar passion for justice. I am glad you inherited the good strain. Politically, I am a definite socialistic demo- crat—always left.” But Ford added that, having paid close attention to the de- velopment of the Soviet Union, he was convinced that Communism was not the answer to the world s problems because it ran the risk of bringing about despotism. Suggesting that Bob keep a combat diary with an eye to writing a book, Ford advised him to be on the alert for details of both comedy and drama. He cautioned his nephew to be as careful as possible in battle against the Fascists. In an anti-Semitic “joke” that seemed particularly at odds with the cause for which Bob wasfighting, Ford added that he hoped aJew wouldn’t be feeding Bob ammunition.

Ford addressed a public rally held by the group at the Shrine Auditorium on January 30, 1938, the fifth anniversary of Adolf Hitlers rise to power. The rally’s theme was “The Nazi Menace in America.” That spring Ford became involved in a labor issue that seemed relatively in- nocuous at the time but would have unexpected ramifications years later for his friend and colleague Frank Capra. Ford joined the picket line on the first day of the strike, along with fellow SDG board members Capra and Herbert Biberman. Dunne and Robert Montgomery, the president of the Screen Actors Guild, also were there rep- resenting their guilds. “We spent about five minutes walking up and down the picket lines and had our pictures taken,” Dunne recalled. A photo of Ford, Capra, and Biberman standing in front of the newspaper building “as they joined the picket line” appeared in the Hollywood Citizen-News Striker (an ad hoc publication by the striking employees) on June 1 under the heading “Film Directors Give Aid.” There was a mild backlash within the Directors Guild. At a board meeting on June 6, the conservative director Howard Hawks criticized the publication of the picketing invitation in the Bulletin, and the board re- served the right to approve such action in the future.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities was created on May 26, just nine days after Ford appeared with his colleagues on the picket line. HUAC was already turning its sights on Hollywood as part of its mandate to investigate “the extent, character, and objects of un-American propaganda activities in the United States.” Referring to a report in the West Coast Communist Party newspaper People’s World, HUAC placed an item in a file on Capra indicating that: “The 30 May 1938 issue of the People’s World described CAPRA as a member of the picket line in the Hollywood Citizen s [sic] News Strike which was Communist inspired.” That citation, among similar charges, would cause problems for Capra during the postwar Hollywood blacklist era, forcing him to call on Ford for help. During the same period of the late thirties when Ford considered himself “a definite socialistic democrat—always left,” he served in a semiofficial capacity as a spy for U.S. Naval Intelligence. Fords spying missions to Mexico are amply documented in his U.S. Navy personnel file and his personal papers, but Dan Ford’s biography, written before John Ford’s official navy file was released, mocks his grandfather’s accounts of these missions. The book’s account of a mission to Baja California in 1939 suggests that Ford was “fantasizing” and that his objec- tive was not gathering genuine intelligence but “advancing himself in the Navy.

Pappy does not quote the letter of commendation Ford received from the navy in January 1940 for the seven-page report he filed on possible Japanese military activity in Mexico. The navy praised his “initiative in securing the valuable information contained in your very interesting Intelligence Report of 30 December 1939 on Lower California and the Gulf of California. Your ef- forts to obtain this information, voluntarily and at your own expense, are con- sidered very commendable. Japanese infiltration south of the Mexican border was of particular concern to the man who supervised Ford’s missions, Captain Ellis M. Zacharias, chief intelligence officer of the Eleventh Naval District at San Diego, the district in which Ford served as a naval reserve officer. Zacharias worried that Japanese fishing trawlers might be surveying Mexican waters for the Imperial Navy and stockpiling supplies and equipment for possible later use by submarines. Ford’s cover as a yachtsman, sport fisherman, and carouser gave him the perfect op- portunity to sail from port to port observing Japanese activity. While some of the fishermen and other Japanese whom Ford observed on such trips may well have been innocent of any military purpose, it’s too easy in hindsight to dis- count the genuine fears the United States had about the vulnerability of Mex- ico, Central America, and South America to such infiltration in the years prior to the onset of war with Germany and Japan. There is no doubt that such fears were exaggerated. Public hysteria over a possible Japanese invasion led to one of the worst episodes of injustice in American history, the interning of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps for the duration of the war. But during the early days of America’s involvement in the war, the Japanese mili- tary did make some attempts to attack the western states with submarines, miniature airplanes, and balloon bombs.

General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, director of the Office of Strate- gic Services (OSS), reported in 1943 that Ford had “devoted himself to the study of intelligence matters” during much of his time in the Naval Reserve before World War II. On September 15, 1941, four days after being called to Washington for active duty in the navy, Ford wrote in a navy document that he had performed “several Naval Intelligence assignments” as a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve. “I have made numerous voyages [on the Araner] to Hawaii, Panama, the Mexican Coast, and various places on the Pa- cific,” he elaborated in a 1941 navy biographical sheet. “Trips to the Mexican Coast have been mainly at the suggestion of Captain Zacharias, USN.” This kind of activity began soon after Ford received his commission in September 1934, and continued at least until February-March 1941, when he undertook a three-week mission to Mazatlan and La Paz. In his October 1935 annual fitness report for the navy, Ford wrote, “Under Instructions from Director Naval Reserve llth Naval District [Capt. Herbert A. Jones] have made research covering camera photography and camouflage problems. As Master of my 108-foot Ketch Araner have cruised Coast of Mex- ico to Acapulco visiting en route La Paz, Mazatlan—Tres Marias [Islands]— Cleopha—Manzanillo—Have just completed a round trip to Hawaii on Araner visiting all the Islands. Visited the Sub Base V-4 . . .” Jones described Ford in the same report as an “Excellent officer, enthusiastic, loyal, intelligent, influential in his community. Has been working intensely in an effort to col- lect photographic and camouflage information likely to be of value to the Navy.”

Ford’s intelligence activities eventually led to his formation of the Field Photographic Branch of the OSS to document military activity in World War II and provide mapping and other photographic reconnaissance information. Ford began organizing Field Photo, as it was called, on an unofficial basis as a Naval Reserve unit in 1939, but it was not fully operational until September 1941. Ironically, the navy declined to accept Ford’s unit for wartime service, forcing him to turn for backing to Donovan’s newly formed overseas intelli- gence agency. However, Ford’s prewar activities in concert with Naval Intelli- gence and the conditions of his recruitment into the Naval Reserve clearly indicate the navy’s awareness that he would be a valuable asset in any future combat situation. As part of his preparation during the 1930s, Ford studied how to make training films and conducted a study of aerial and sea photography. He exag- gerated somewhat when he claimed to have “pioneered combat and sea photography” for the navy. But it was true that he “visualized the great im- portance of photography in times of peace and war,” as his commanding offi- cer, W W Waddell, wrote in February 1941. In addition to providing data for the Office of Naval Intelligence, Ford’s reconnaissance and mapping of Mex- ican waters gave him valuable practice in the art of photographic documenta- tion.

Ford’s reports were “of considerable importance/’ he was told in a 1936 let- ter of commendation from navy lieutenant commander A. A. Hopkins. “For your own personal information, [I] will state that of the six yachts who [sic] have been requested to make observations during the past two years, the Araner, its owner and commander are the only ones who have made entrance to the area you explored and who have brought back the data wanted.” The ONI noted in July 1936 that Ford had contributed “valuable and most inter- esting data on Scammon Lagoon” in Baja California. For that report, Ford spent two days with Araner captain George Goldrainer and crew members photographing and charting the area from launches. Ford wrote that while he had seen no indication of a Japanese presence, the isolated lagoon was “close enough to shipping lanes to serve as an ideal place to either stockpile supplies or to serve as a rendezvous point for submarines and sub tenders.”

On his 1939 trip to Baja California and the Gulf of California, Ford was accompanied by Mary; his longtime cinematographer George Schneiderman;Schneidermans wife, Rita; John Wayne; Ward Bond; Preston Foster; and Wingate Smith. Mary and the Schneidermans provided assistance in Ford’s es-pionage activities, but the others were just along for the carousing. The entire group spent a fair amount of time in Mexican bars while cruising the route from Magdalena Bay to Cabo San Lucas and Mazatlan. Ford and Schneiderman amused themselves on the Araner at one point by making a 16mm movie composed of “artistic” studies of beer bottles. Upon his return to Los Angeles, Ford prepared his seven-page report for Zacharias, the most detailed such document available in his files. Most of the report concerns his reconnaissance of Muertos Bay at Guaymas, where he spent three days fishing. Schneiderman used a still camera with a telephoto lens to take photographs of Japanese trawlers. Ford also included observations of a fellow passenger on a train trip in Mexico, “a large Japanese, [an] obvious Army type” carrying an expensive Leica camera with a telescopic lens. This man gave orders to groups of other Japanese he met at various stops along the way, and Ford thought he was a spy:”Takes pictures only of bridges and oil tanks. He was sublimely indifferent to the scenery and the picturesque Mexi- can hills we passed through.”

Ford’s report on Muertos Bay contains many details about ships and naval uniforms, but what is most remarkable is the way it reflects his keen eye for de- tails of human behavior. This power of observation, when translated into cin- ematic terms, helps account for his visual and dramatic authority as a director. He wrote in his report:

When entering Guaymas harbor, I thought for a moment I was in Moji Straits. The Japanese shrimp fleet was lying at anchor. Four- teen steam trawlers two to two hundred and fifty tons . . . two mother ships five to six hundred tons. . . . I believe the Company that owns them is Nippon Kaisha. . . . the majority of the stock is owned by the Imperial Family, the remainder by Matsui. The most striking point concerning this fleet is its personnel. This has me completely baffled. The crews come ashore for lib- erty in well-tailored flannels, worsted and tweed suits . . . black service shoes smartly polished. . . . The men are above average height. . . young . . . good-looking and very alert. All carrying themselves with military carriage. . . . None of these young men spoke English. Some had a smattering of Spanish. I cannot com- pare them to any ratings in our service . . . unless possibly to the University Naval Reserve Units such as the one at the University of California. . . . Aboard each trawler three or four young officers were sta- tioned, who never went ashore unless in uniform. The uniform, with the exception of the cap, badge and stripe was the regulation braid-bound Imperial Navy uniform, smartly cut and well pressed. The cap badge while not regulation had the Rising Sun motif. The Ensign stripe was black, tilted. These young men were tall, straight as ramrods, high cheek-boned, with aquiline features, definitely aristocratic. For want of a better word I would call them the Samurai or military caste. (During three trips to Japan I have studied this type very closely. I’m positive they are Naval men.) . . .

I beg to submit the following opinion. It is my belief that the crews and officers of this shrimp fleet belong to the Imperial Navy or Reserve. The crews are not the same class of fishermen that I have seen so many times in Japan. It is my opinion that these young men are brought here from time to time to make themselves absolutely familiar with Mexican waters and par- ticularly the Gulf of California. . . . It is plausible to assume that these men know every Bay, Cove and Inlet in the Gulf of Cali- fornia, a Bay which is so full of islands, and so close to our Ari- zona borderline. They constitute a real menace. Although I am not a trained Intelligence Officer, still my profession is to observe and make distinctions. I have observed well in Japan. I will stake my pro- fessional reputation that these young men are not professional fishermen. In a 1943 report, Commander W. H. Vanderbilt, USNR, head of strategic services for the ONI, described Ford as “fully qualified as an intelligence offi- cer. I doubt if he has the technical experience for certain official duties, but he is a man of broad knowledge, wide experience, and sound judgment.”

With war coming ever closer to America in 1940, the need for modern, so- phisticated combat photography units was becoming more urgent. Ford had foreseen that need when he joined the Naval Reserve in 1934 and began plan- ning for possible American involvement in war with Germany and Japan. His reconnaissance missions to Mexico and elsewhere on behalf of the navy, which continued until February 1941, were part of those preparations. But despite the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, the United States remained largely isolationist, and its military bureaucracy was slow to mod- ernize photographic operations. Impatient with the situation and unaccus- tomed to going through official channels, Lieutenant Commander John Ford, USNR, took it upon himself in 1939 to begin organizing what originally was called the Naval Volunteer Photographic Unit, devoted to “carrying out the original plan” for which he had been commissioned.

“John Ford’s Navy,” as it was known in Hollywood, recruited and trained experienced technicians from the studios’ camera, sound, laboratory, and crafts departments. Ford received valuable organizational assistance from Gregg Toland, who trained the unit’s cinematographers; sound engineer Edmund H. Hansen, a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve, who ran the sound di- vision; and the dapper, diplomatic Lieutenant Commander Alfred J. “Jack” Bolton, USN (Ret.), who served as a liaison between Hollywood and the navy. Ford submitted a written proposal to the navy in 1940 for acceptance of his volunteers as a Naval Photographic Organization to document naval combat activities for operational, intelligence, historical, and propaganda purposes. The proposal also was signed by Bolton; Hansen; Ford’s Air Mail screenwriter Frank W. “Spig” Wead, a retired lieutenant commander in the navy; and Ford’s producing partner in Argosy Pictures, Merian C. Cooper, then a captain in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. They explained that a more modern photo- graphic organization was needed because the current war already had seen an unprecedented use of photography in naval and other military operations, particularly by the Germans. Pointing out that the use of film reconnaissance and documentation of combat could change the course of battle, they set forth some far-reaching proposals. Predicting the use of radio and television to transmit films of operations and intelligence, they noted that “the develop- ment of television for such purposes is an urgent naval photographic research problem, not beyond early realization.”

Most of the proposal, however, was spent discussing the morale and propa- ganda value of motion pictures to obtain “the complete support of the na- tion” for naval operations: “To our own people, radio, newspapers, [and] motion pictures blast contrary ideas back and forth. Some say our Navy is old- fashioned, . . . The average man has no conception of our Navy’s weight, prowess, power, high morale, and striking force. A series of films which show factually the power of the American Navy is bound to give a psychological lift to the whole nation. Let them see the rigors of training; the skill of execution in maneuvers; how money is spent for sea power. . . . “The German nation in seven years was changed from an indifferent, apa- thetic, despondent people into a mighty military machine, by the use of radio, printed words and motion pictures, until they were prepared to follow one man and fight the world. “Our use would be different. Our morale purpose is to show that a Democ- racy can and must create a greater fighting machine, in spirit and being, than a dictator power.”

In April 1940, through Bolton’s intercession, Ford’s navy acquired official status as the Naval Reserve Photographic Section of the San Diego—based Eleventh Naval District. Ford was appointed recruiting officer to enlist photo- graphic personnel and instructors to study the use of photography in “tactics, ballistics and training and historical films.” Believing strongly in the cause of the upcoming fight against fascism, Ford threw himself with enthusiasm into the practical tasks at hand, serving without pay. But his emotions were espe- cially stirred by the ceremonial aspects of military command, the drilling, training, and parading with the full panoply of flags, uniforms, and weaponry. Seeing World War II service as an exciting adventure that would make up for his failure to win acceptance to Annapolis and his lack of service in World War I, Ford approached the upcoming fray with something of a Walter Mittyish perspective. In a 1941 navy biographical sheet, Ford boyishly noted that though he had won two Academy Awards and three awards from the New York Film Critics Circle (“supposedly the greatest honor in the industry”), as well as honors for his films from Italy and Belgium, “I state with pardonable pride that I am the proud possessor of the Small Arms Expert’s medal.” Ford’s Photographic Section started regular weekly training with 38 officers and 122 enlisted men. By May 1941, it had signed up such men as Cooper; cameramen Joseph H. August, Sid Hickox, John Fulton, Alfred Gilks, and Harold Rosson; editors Otho Lovering and Robert Parrish; and special effects technician E. R. “Ray” Kellogg. At its full strength, the section included about 300 men, many of whom joined after the draft was reinstated in September 1940 and American involvement in the war seemed increasingly inevitable. Before Pearl Harbor, about a third of Ford’s men volunteered for active service in the U.S. Navy.

Every Tuesday night from eight to midnight, his ragtag band of volunteers drilled and received instruction on Twentieth Century—Fox soundstages, thanks to Zanuck, who had military ambitions of his own. The men used weapons from the Fox prop department and uniforms borrowed from the Western Costume Company. They took supplemental classes on Monday and Wednesday evenings at other locations, including the Los Angeles Naval Re- serve Armory, learning how to use various types of camera and sound equip- ment under wartime conditions and how to develop and print their own motion pictures and stills in the field or on board ship. The training sessions included Toland’s “Ten-Minute Talk on Elementary Photography” and a course in “Military Indoctrination” taught by Ford, Bolton, Jack Pennick, and Ben Grotsky. Pennick, a pug-faced ex-marine, was Ford’s loyal drillmaster, and Grotsky, a colorful character from Brooklyn, came out of retirement as a chief petty officer in the navy to join the unit. Ford’s attempts to have his Photographic Section accepted as part of regular navy operations were frustrated. His unorthodox approach to documentary filmmaking was threatening to military bureaucrats used to following safe, es- tablished procedures. Partly to show the brass what the unit could do, and partly for their own training, Ford’s enlisted men made a film of the mobiliza- tion and induction ceremonies of the newly formed California State Guard, held at the Santa Anita racetrack. Shot in 1940 as a shakedown assignment without help from their commissioned officers, the completed film was shown throughout California to encourage enlistment in the guard. But the navy stalled when Ford volunteered his men. Undaunted, sure they would be needed, they continued training in the expectation that America soon would enter the war.

Black Shoe Carrier Admiral: Frank Jack Fletcher at Coral Sea, Midway and Guadalcanal (John B. Lundstrom, 2006).

Sunrise on 13 December 1941 revealed Oahu’s familiar profile to Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, the commander of Cruiser Division Six in the U.S. Pacific Fleet. His flagship, heavy cruiser Astoria, prepared to enter the cozy confines of Pearl Harbor. After eighteen months’ duty in the Hawaiian Islands, going back into base should have been routine, but not on that occasion. Six days before, Japanese aircraft carriers surprised the fleet at Pearl Harbor and opened the Pacific portion of World War II. The task force in which Fletcher served was near Midway and pursued the raiders but fortunately—as it turned out—never caught up with them. Now he was returning for a new assignment. Radio dispatches from Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet (Cincpac), painted a grim picture. Nothing, though, prepared Fletcher for what he saw. First there was a crashed U.S. carrier plane perched in the shallow water, then to starboard gutted Hickam airfield. Aground after her valiant sortie was the battleship Nevada, “Her nose in the beach and her bow partly submerged, her deck plates all hogged up from bomb hits.” Beyond, in Battleship Row, the sunken California rested in the mud, as did the West Virginia; the Oklahoma presented just her “red bottom and one bronze propeller,” and the Arizona had blown apart. Only the hurt Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Tennessee remained seaworthy. Hundreds of carrier-based torpedo planes, dive bombers, level bombers, and strafing fighters sank or damaged eighteen ships and ravaged Oahu’s airfields of 188 planes. Nearly twenty-four hundred Americans died, but so far as anyone knew, the victory cost Japan a few midget submarines and an insignificant number of aircraft.1 The “horrible sight” of the once magnificent battle line reduced to an impotent shambles shook Fletcher to the core. Like Kimmel and nearly all the senior officers, he was a “black shoe,” a nickname derived from the color of the footgear most naval officers wore. Black shoes were surface warriors, to whom big-gunned and heavily armored battleships, the “major fighting power of the U.S. Fleet,” represented true naval might. “Aircraft carriers—the pride of the “brown shoe” naval aviators—they considered secondary to battleships in the navy’s prime mission of destroying the enemy battle fleet. Conceding carriers were valuable for reconnaisance, air cover, attacking weakly protected forces, and raiding ground targets, black shoes avowed only battleships could defeat other battleships and win supremacy on the seas. The unfolding Pacific War stood the black-shoe world on its head. Not only did Japan, a despised adversary, demolish the battle line, but also they accomplished that astounding feat by massing carriers to project vast firepower. The successful prosecution of the war now required air supremacy, both from the seagoing airfields and shore bases. Nailing that last point was the almost equally shocking destruction, on 10 December, of the modern British battleship Prince of Wales and old battle cruiser Repulse by land-based medium bombers. Not caught in harbor like the Italian battleships in 1940 at Taranto and the U.S. battleships at Pearl Harbor, they succumbed at sea to a blizzard of aerial torpedoes and heavy bombs.2”

Alone among his peers, Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku, commander of the Combined Fleet, recognized carrier air power to be the trump card in modern naval warfare. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) already possessed the strongest such capacity in the world. He resolved to use carriers to open the war in a daring stab to the heart of U.S. naval strength at remote Pearl Harbor. Sinking the Pacific Fleet’s battleships and carriers would cover the seizure of the Philippines and Southeast Asia and give Japan vital time to consolidate its defense of newly won gains. To attack Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto created an immensely powerful striking force of no fewer than six aircraft carriers, wielding more than four hundred planes. Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi’s Kidō Butai (literally “mobile force,” but the best term in English is “striking force”) comprised carriers Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku, two fast battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, sixteen destroyers, three submarines, and seven oilers. Seventeen other subs (including five equipped with midget subs) would rampage Hawaiian waters.

On 26 November the Kidō Butai secretly sortied from northern Japan to venture three thousand miles across the barren, stormy North Pacific bound for a launch point 230 miles north of Oahu. Such an odyssey could only occur because the IJN recently developed the capability to fuel heavy ships under way similar to its principal opponent, the U.S. Navy, and greatly exceeding Britain’s Royal Navy. On 7 December (8 December, Tokyo time), Nagumo delivered a crushing assault by 350 aircraft in two waves that nearly annihilated the Pacific Fleet. The cost of such colossal results was only twenty-nine planes (with many others shot up), five midget subs, and sixty-four lives.3One bold and brilliant stroke transformed the entire character of naval warfare, although even Yamamoto did not fully fathom the extent of his revolution. His massing of six powerful carriers was totally unprecedented when all other navies reckoned their carriers in units of ones or twos. Yamamoto’s innovation equated to a kind of 1941 atomic bomb. U.S. naval intelligence never understood prior to 7 December that Japan fashioned a single operational task force completely around several carriers, instead of the usual practice of attaching individual carrier divisions to different fleets. Each of the three principal Pacific Fleet task forces included only one carrier, with no immediate plans of operating more than one carrier together. ”

Not having as yet made the huge intellectual leap of thinking of carriers in multiple units, it is hardly surprising that the U.S. Navy brass did not accord their future opponents any more insight in that regard. The high command simply did not believe that a single carrier raid could seriously harm Pearl Harbor. It was truly a miracle the two U.S. carriers in the Hawaiian region, the Enterprise and Lexington, survived the outbreak of the war intact, while the Saratoga, the third, happened to be at San Diego. A few days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Capt. Charles H. “Soc” McMorris, the Pacific Fleet War Plans officer, conceded Japan’s failure to destroy the U.S. carriers left Cincpac a “very powerful” weapon, but certainly it was one that neither he nor his boss Kimmel had truly appreciated.4 Thus the aircraft carrier supplanted the battleship as the major factor in the Pacific naval war. The same, Fletcher discovered, was more or less true for battleship admirals. Had the massive fleet campaign in the central Pacific unfolded as Kimmel envisioned prior to 7 December, Fletcher, although a well regarded subordinate, would have played only a relatively minor role. Now as the fighting fell to the more junior admirals, Fletcher proved to be in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. Two days after he returned to Pearl Harbor he received a combat mission of great importance—relief of embattled Wake Island two thousand miles west of Oahu. His new task force comprised the Saratoga, three cruisers, nine destroyers, a seaplane tender transporting ground reinforcements, and a fleet oiler. Therefore Fletcher, a trusted flag officer who nevertheless totally lacked naval aviation experience, stepped into carrier command that afforded him an extraordinary opportunity to be among the first U.S. admirals to fight a new form of naval war. No one else played a more important role in the crucial 1942 carrier battles that helped turn the tide of war in the Pacific.

Born on 29 April 1885 in Marshalltown, Iowa, the son of a Union veteran, Frank Jack Fletcher grew up in comfortable middle-class circumstances. His uncle Frank Friday Fletcher, an 1875 Naval Academy (USNA) graduate, inspired his naval career. Fletcher himself graduated from Annapolis in 1906, ranked twenty-sixth out of 116 midshipmen. His years at Annapolis overlapped numerous other midshipmen, who some forty years hence played a crucial role in his life as well as the nation’s.

A man will search his heart and soul, Go searchin’ way out there.

His peace of mind he knows he’ll find, But where, O Lord, Lord, where?

THE THEME SONG FROM THE SEARCHERS (1956)

“I looked at a million photographs because this is the dot theory of reality, that all knowledge is available if you analyze the dots.” There was a slight crackle in his voice that sounded like random radio noise produced by some disturbance of the signal. He acquired original film. He brought in darkroom equipment. He ate his meals with a magnifier around his neck. The house was filled with contact sheets, glossy prints, there were blowups pinned to clotheslines rigged through several rooms. His wife and child fled to England to visit relatives because Marvin somehow married English. He hired a private detective with an intermittent nosebleed. They placed ads in the personal columns of sporting magazines, trying to locate people who’d sat in section 35, where the ball went in. There was the photographic detailwork, the fineness of image, the what-do-you-call-it into littler units. “Resolution,” Brian said. And then there was the long journey, the suitcase crawl through empty train stations, the bitter winter flights with ice on the wings, there was the weary traipse, a word he doesn’t hear anymore, the march into people’s houses and lives–the actual physical thing, unphotographed, of liver-spotted hands and dimpled chins and the whole strewn sense of what they remember and forget.

1. The widow on Long Island turning a spoon in her cup.

2. The gospel singer named Prestigious Booker who kept a baseball in an urn that held her lover’s ashes.

3. The ship on the dock in San Francisco–don’t even bring it up.

4. The man in his car in Deaf Smith County, Texas, the original middle of nowhere.

5. A whole generation of Jesus faces. Young men everywhere bearded and sandaled, bearded and barefoot–little peeky spectacles with wire frames.

6. Marvin’s sense of being lost in America, wandering through cities with no downtowns.

7. The woman on Long Island, what’s-her-name, whose husband was at the game–she served instant coffee in cups from a doll museum.

8. The Coptic family in Detroit–never mind, it’s too complicated, riots and fires in the distance, tanks in the streets.

9. The detailed confusion of Marvin’s narrative, people’s memories mixed with his own, shaped to bending time.

10. A tornado touching down, skipping along the treetops in an evil weave, the whole sky filthy with flung debris.

11. Whose husband was in the footage Marvin analyzed, scrambling for the baseball, and all she had in the house was instant. 12. Riding up the side of a building in an elevator that’s transparent.

13. The ship on the dock–please not now.

14. What a mystery all around him, every street deep in some radiant amaze.

Brian listened to all this and he heard the music end and begin again, the same piano piece, and this was not the second time he was hearing it but maybe the eighth or ninth, and he listened to Marvin’s dot theory of reality and felt an underlying force in this theme of the relentless photographic search, some prototype he could not bring into tight definition. “A thousand times I said. How long do I look? Why do I want it? Where is it?”

He advertised for amateur film footage of the game and acquired a few minutes of crude action that showed a massive pulsing blur above the left-field wall shot by a man in the bleachers. He brought in an optical printer. He rephotographed the footage. He enlarged, repositioned, analyzed. He step-framed the action to slow it down, to combine several seconds of film into one image. He examined the sprocket areas of the film searching for a speck of data, a minim of missing imagery. It was work of Talmudic refinement, zooming in and fading out, trying to bring a man’s face into definition, read a woman’s ankle bracelet engraved with a name. Brian was shamed by other men’s obsessions. They exposed his own middling drift, the voice he heard, soft, faint and faraway, that told him not to bother. Marvin’s wife and child came home and went away again. The house had become a booby hatch of looming images. The isolated grimace, the hair that juts from the mole on the old man’s chin. Every image teeming with crystalized dots. A photograph is a universe of dots. The grain, the halide, the little silver things clumped in the emulsion. Once you get inside a dot, you gain access to hidden information, you slide inside the smallest event. This is what technology does. It peels back the shadows and redeems the dazed and rambling past. It makes reality come true. (Underworld, Don DeLillo, 1998, page 77)

The Movement Image (Deleuze)

The Western is a fourth great genre, and is solidly anchored in a milieu. Since Ince, and according to the formula S A S ‘ (we will see that this is not the only formula of the Western), the milieu is the Ambiance or the Encompasser. Here, the principal quality of the image is breath, respiration. It not only inspires the hero, but brings things together in a whole of organic representation and contracts or expands depending on the circumstances. When colour takes possession of this world, it follows a chromatic scale where it diffuses, and where the saturated [saturé] resonates with the faint [lavé] (we will rediscover this ambiant colour in the artificial sets [décors] of Ford’s How Green Was My Valley). The ultimate encompasser is the sky and its pulsations, not only in Ford, but also in Hawks who makes one of the characters in Big Sky say: it is a big country, the only thing which is bigger is the sky. . . .Encompassed by the sky, the milieu in turn encompasses the collectivity. It is as representative of the collectivity that the hero becomes capable of an action which makes him equal to the milieu and re-establishes its accidentally or periodically endangered order: mediations of the community and of the land* are necessary in order to form a leader and render an individual capable of such a great action. We recognise the world of Ford, with the intense collective moments (marriage, festival, dances and songs), the constant presence of the land and the immanence of the sky. Some have concluded from this that there is a closed space in Ford, without real movement or time.5It seems to us, rather, that movement is real but, instead of happening from part to part, or in relation to a whole whose change it would express, it happens in an encompasser, whose respiration it expresses. The outside encompasses the inside, both communicate, and we advance by passing from the one to the other in both directions, as in the images of Stagecoach where the diligence inside alternates with the diligence seen from the outside. One can go from a known to an unknown point, the promised land, as in Wagonmaster: the essential point remains the encompasser which includes both and which expands as one advances painfully and contracts when one stops and rests. Ford’s originality lies in the fact that only the encompasser gives measure to movement, or the organic rythmn. It is thus the melting pot of minorities, that is, what brings them together, what reveals their correspondences even when they appear to be opposed, what already shows the fusion between them necessary for the birth o f a nation: for example, the three groups o f persecuted people who meet in Wagonmaster – the Mormons, the travelling players and the Indians.

If one remains at this first approximation, one is in an SA S structure which has become cosmic or epic – the hero becomes equal to the milieu via the intermediary of the community, and does not modify the milieu, but re-establishes cyclic order in it.6However, it would be dangerous to reserve an epic genius for Ince and Ford, attributing to other more recent directors the invention of a tragic or even a romantic Western. The application of Hegel’s and Lukács’ formula of the succession of these genres works badly for the Western: as Mitry has shown, from the outset the Western explores all the directions – epic, tragic, romantic – with cowboys who are already nostalgic, solitary, ageing, or even bom losers, or rehabilitated Indians. Throughout his work, Ford constantly grasps the evolution of a situation, which introduces a perfectly real time. There is certainly a great difference between the Western and what can be called the neo-W estem; but it is not explicable in terms o f a succession of genres, or of a transition from the closed to the open in space. In Ford, the hero is not content to re-establish the episodically threatened order. The organisation of the film, the organic represen tation, is not a circle, but a spiral where the situation of arrival differs from the situation of departure: SAS’. It is an ethical rather than an epic form.

For Ford, as for Vidor, society changes, and does not stop changing, but its changes take place in an Encompasser which covers them and blesses them with a healthy illusion as continuity of the nation. […] Finally, the American cinema constantly shoots and reshoots a single fundamental film, which is the birth of a nation-civilisation, whose first version was provided by Griffith. It has in common with the Soviet cinema the belief in a finality o f universal history; here the blossoming of the American nation, there the advent of the proletariat. But, with the Americans, organic representation is obviously unaware of dialectical development; it and it alone is the whole of history, the germinating stock from which each nation- civilisation detaches itself as an organism, each prefiguring America. This is the origin of the deeply analogical or parallelist character of this conception of history, as it is found in Griffith’s Intolerance which intersperses four periods, or in the first version of Cecil B. De Mille’s Ten Commandments, which puts two periods into parallel, the latter being America. The decadent nations are sick organisms, like Griffith’s Babylon or De Mille’s Rome. If the Bible is fundamental to them, it is because the Hebrews, then the Christians, gave birth to healthy nation-civilisations which already displayed the two charac teristics of the American dream: that of a melting pot in which minorities are dissolved and that of a ferment which creates leaders capable of reacting to all situations. Conversely, Ford’s Lincoln recapitulates biblical history, judging as perfectly as Solomon, bringing about, like Moses, the transition from the nomadic to the written law, from nomos to logos, entering the city on his ass like Christ (Young Mr Lincoln). And if the historical film thus forms a great genre of the American cinema, it is perhaps because, in the conditions peculiar to America, all the other genres were already historical, whatever their degree of fiction: crime with gangsterism, adventure with the Western, had the status of pathogenic or exemplary historical structures.

It is easy to make fun of Hollywood’s historical conceptions. It seems to us, on the contrary, that they bring together the most serious aspects of history as seen by the nineteenth century. Nietzsche distinguished three of these aspects, ‘monumental history’, ‘antiquarian history’ and ‘critical’, or rather ethical, history.10The monumental aspect concerns the physical and human encompasser, the natural and architectural milieu. Babylon and its defeat, in Griffith, the Hebrews, the desert and the sea which opens; or, in Cecil B. De Mille, the Philistines, Dagon’s temple and its destruction by Samson, are immense synsigns which make the image itself monumental. T h e treatment can be very different; whether great frescos in The Ten Commandments, or aseries ofengravings in Samson and Delilah, the image remains sublime, and although the temple of Dagon can trigger off our laughter, it is an Olympian laughter which takes hold of the spectator. According to Nietzsche’s analysis, such an aspect of history favours the analogies or parallels between one civilisation and another: the great moments of humanity, however distant they are, are supposed to communicate via the peaks, and form a ‘collection of effects in themselves’ which can be more easily compared and act all the more strongly on the mind of the modem spectator. Monumental history thus naturally tends towards the universal, and finds its masterpiece in Intolerance, because the different periods do not simply follow one another, but alternate through an extraordinary rhythmic montage (Buster Keaton gives a comic version of it in Three Ages). And, in whatever manner it proceeded, a confrontation of periods continued to be the dream of the monumental history film even in Eisenstein.11This conception of history has, however, abigdisadvantage:thatoftreatingphenomena as effects in themselves, separate from any cause. Nietzsche had already pointed this out and it is what Eisenstein criticises in the American historical and social cinema. Not only are civilisations considered to be parallel, but the principal phenomena of a single civilisation, for example, the rich and the poor, are treated as ‘two parallel independent phenomena’, as pure effects that are observed, if necessary with regret, but nevertheless without having any cause assigned to them. Hence, it is inevitable that causes are rejected from another perspective, and only appear in the form of individual duels which sometimes oppose a representative of the poor and a representative of the rich, sometimes a decadent and a man of the future, sometimes a just man and a traitor, etc. Eisenstein’s strength thus lies in showing that the principal technical aspects of American montage since Griffith – the alternate parallel montage which makes up the situation, and the alternate concurrent montage which leads to the duel – relate back to this social and bourgeois historical conception. It is this essential defect that Eisenstein wants to remedy: he demands a presentation of true causes, which would have to subject the monumental to a ‘dialectical’ construction (in any event, the struggle of classes instead of that of a traitor, a decadent or an evildoer).

If monumental history considers effects in themselves, and if the only causes it understands are simple duels opposing individuals, antiquarian history must occupy itself with these as well, and reconstitute their forms which are habitual to the epoch: wars and confrontations, gladiator combats, chariot races, tournaments, etc. And antiquarian history is not satisfied with duels in the strict sense, it stretches out towards the external situation and contracts inrcrïhë means of action and intimate customs, vast tapestries, clothes, finery, machines, weapons or tools, jewels, private objects. T h e orgy allows gigantism and intimacy to coexist. The antiquarian runs parallel to the monumental. Here again facile ironical remarks are made about Hollywood reconstructions, and the ‘brand-new’ appearance of the props: the new is, as in the antiquarian, the sign of the actualisation of the epoch. T h e fabrics become a fundamental element o f the historical film, especially with the colour-image, as in Samson and Delilah, where the display of cloth by the merchant and Samson’s theft of the thirty tunics, constitute the two peaks of colour. Machines also form a peak, whether they give birth to a new nation- civilisation, or whether on the contrary they announce its decline or disappearance. In his only historical film strictly speaking, Land o f the Pharaohs, Hawks only seems to be interested in one moment, the whole ending, where the architect has become an engineer as well, and has set up an extraordinary new machine for the Pharaoh which combines sand and stone, flowing sand and descending stone, so that the pyramid’s funeral chamber can be absolutely hermetically closed.

Finally, it is true that the monumental and antiquarian conceptions o f history would not come together so well without the ethical image which measures and organises them both. As Cecil B. De Mille says, it is a matter of Good and Evil, with all the temptations or the horrors of Evil (the barbarians, the unbelievers, the intolerant, the orgy, etc.). The ancient or recent past must submit to trial, go to court, in order to disclose what it is that produces decadence and what it is that produces new life; what the ferments of decadence and the germs of new lifeare, the orgy and the sign ofthe cross, the omnipotence ofthe rich and the misery of the poor. A strong ethical judgement must condemn the injustice of ‘things’, bring compassion, herald the new civilisation on the march, in short, constantly rediscover A m erica. . . more especially as, from the beginning, all examination of causes has been dispensed with. The American cinema is content to illustrate the weakening of a civilisation in the milieu, and the intervention of a traitor in the action. But the marvel is that, with all these limits, it has succeeded in putting forward a strong and coherent conception of universal history, monumental, antiquarian and ethical.

Eisenstein's Mexico, Trotskydead, Ford's conversation on the Baja California

John Ford wrote an Intelligence Report of 30 December 1939 on Lower California and the Gulf of California. Trotsky (https://www.historytoday.com/archive/trotsky-offered-asylum-mexico) was assassinated with a pick axe in Mexico City on 21 August 1940. On September 15, 1941, four days after being called to Washington for active duty in the navy, Ford wrote in a navy document that he had performed “several Naval Intelligence assignments” as a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve. “I have made numerous voyages [on the Araner] to Hawaii, Panama, the Mexican Coast, and various places on the Pa- cific,” he elaborated in a 1941 navy biographical sheet. “Trips to the Mexican Coast have been mainly at the suggestion of Captain Zacharias, USN.” This kind of activity began soon after Ford received his commission in September 1934, and continued at least until February-March 1941, when he undertook a three-week mission to Mazatlan and La Paz. In his October 1935 annual fitness report for the navy, Ford wrote, “Under Instructions from Director Naval Reserve llth Naval District [Capt. Herbert A. Jones] have made research covering camera photography and camouflage problems. As Master of my 108-foot Ketch Araner have cruised Coast of Mex- ico to Acapulco visiting en route La Paz, Mazatlan—Tres Marias [Islands]— Cleopha—Manzanillo—Have just completed a round trip to Hawaii on Araner visiting all the Islands. Visited the Sub Base V-4 . . .” Jones described Ford in the same report as an “Excellent officer, enthusiastic, loyal, intelligent, influential in his community. Has been working intensely in an effort to col- lect photographic and camouflage information likely to be of value to the Navy.”

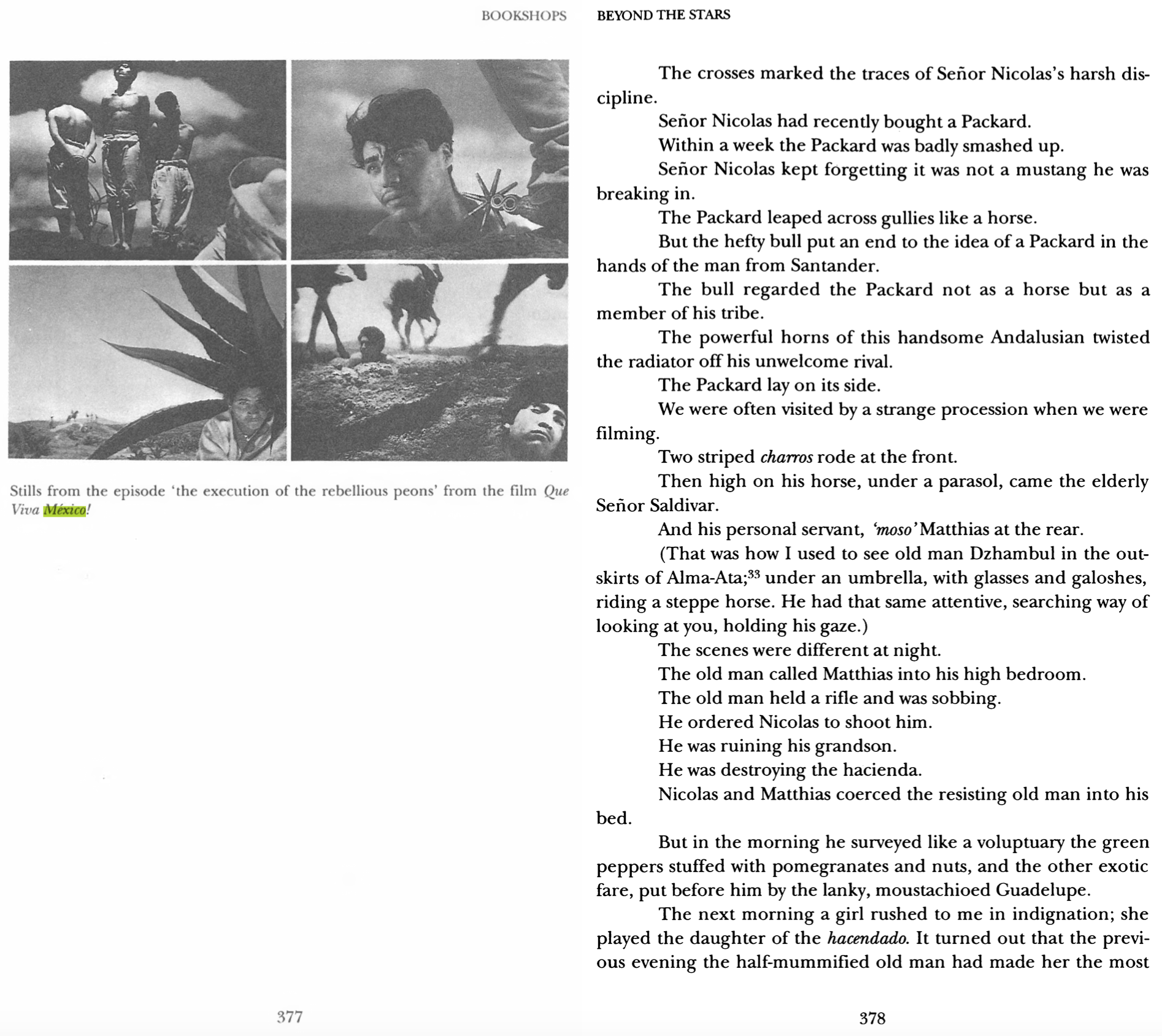

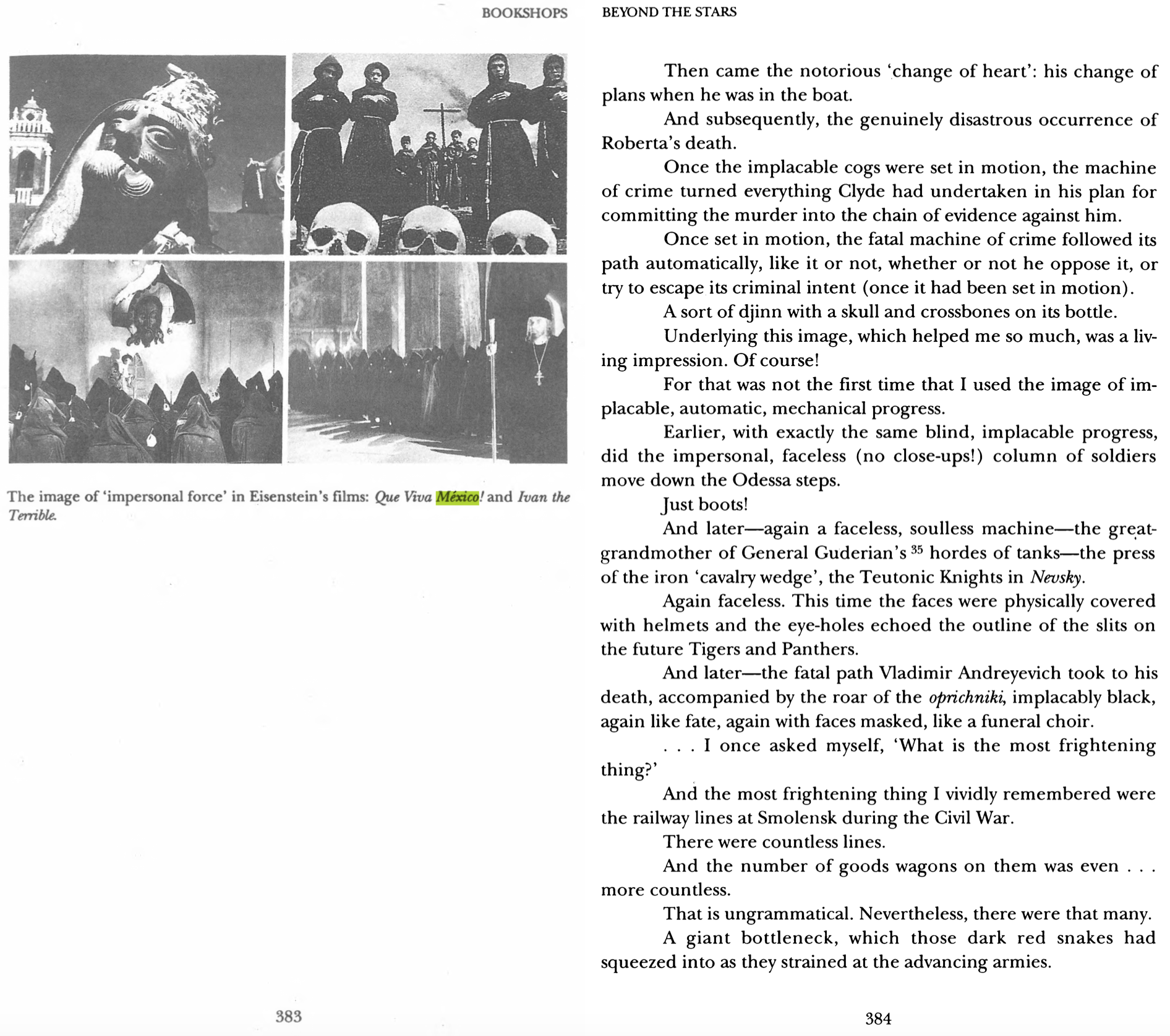

Que viva México! (Russian: Да здравствует Мексика! Da zdravstvuyet Meksika!) is a film project begun in 1930 by the Russian avant-garde director Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948). It would have been an episodic portrayal of Mexican culture and politics from pre-Conquest civilization to the Mexican revolution. Production was beset by difficulties and was eventually abandoned. Jay Leyda and Zina Voynow call it Eisentein’s “greatest film plan and his greatest personal tragedy”.[1] Of all American films made up to now this Young Mr. Lincoln is the film that I would wish, most of all, to have made…. I first saw this film on the eve of the world war. It immediately enthralled me with the perfection of its harmony and the rare still which it employed all expressive means at its disposal. And most of all for the solution of Lincoln’s image” (Sergei Eistenstein, Mr Lincoln by Mr. Ford (1945)) http://www.marshakinder.com/pdf/e29.pdf (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/¡Que_viva_México!)

The director of the museum of ancient Mayan culture in the town of Chichen-Itza (on the Yucatan Peninsula) took it into his head to take me around the museum’s galleries by night when there were no visitors. Museums by night—

especially museums of sculpture—are amazing! I will never forget my nocturnal walk through the halls of ancient sculpture in the Hermitage, during the ‘White Nights’. I was then filming scenes for Octoberin the Winter Palace; I walked along the passageways connecting the Winter Palace to the Hermitage just as the light was shifting.7 It was a fantastic spectacle. The milky bluish twilight streamed in through the windows facing the embankment. And the white shadows, cast by white bodies of Greek stat ues, seemed to come alive and float in the blue gloom. . . . It was different in the museum in Chichen-Itza.

The nights there were pitch black. Tropical. Nor did the Southern Cross, only the small tip of which shyly sticks into the night sky over Mexico, provide any illumina tion. It was too close to the lower border of the magnificent map of the skies which burns above the Yucatan Peninsula and the Gulf of Mexico. The museum’s electricity failed just when we were entering the museum’s ‘secret section’, where the revelry of the ancient Mayan imagination has left its mark on stone artefacts. The whimsicality, absurdity, disproportion and . . . size of the statues increased as they suddenly leaped out at you from the darkness when the match flame flickered here and there. Somewhere, Tolstoy (it may be in Childhood or Boyhood)8 de scribes the effect of lightning when you see galloping horses. The flashes are of such short duration that they light the horses up just one phase at a time.

So they appear motionless.

. . . Here, by contrast, the unexpected flashes as matches are struck in different parts of the room made these still, dark mon sters come alive. Because the angle at which the light burst in altered as the matches burned down, it was as though the stone monsters had had time to change position during the intervals of darkness. They had exchanged places in order to look at the violators of their eternal rest from a new viewpoint—through wide-open, gaping but dead granite eyes. In fact, for a fully understandable reason, most of these stone monsters who loomed out of the darkness did not have eyes. But two barrel-shaped pot-bellied gods in particular had eyes. I was led to them by the hospitable candle held by the keeper of these priceless relics, as we moved through the reefs of stone. Light and shadow alternated. Followed each other. But my Virgil’s [Dante’s] speech flowed continuously as he led me through this dark circle of the underworld of mankind’s early beliefs. Fact about the legends of the gods who possessed the strength of two, flowed endlessly after fact, through this succession of light and dark. The actual succession of light and dark began to resemble the interplay of brilliant reason and the darker depths of the human psyche. Two spherical, granite gods, who had that complete strength, greeted me with a smile. Why two? Each was designed so that he (or she) would have no need of his (or her) partner.

You could only be sure of this by feel. Not only because it was dark in the hall. But because the actual object of investigation was tucked away deep beneath the globes of their bellies. ‘Don’t be afraid to touch,’ my guide told me, ‘touching was and still is considered to have healing effects, endowing the toucher with a great strength. You can feel how smooth the granite has been worn . . .’ I remembered the famous statue of St Peter, in his cathedral in Rome. His foot has been half kissed away by the devoted lips of those humbling themselves before him. Here it was simpler and clearer. Touching the statues of gods, albeit a symbolic action, was to join with them. By touching their ‘double strength’ you yourself would acquire part of that superhuman strength. The miracle-working force suddenly proved itself. The power abruptly came back on, and we finished our pil grimage to these gods with all their contradictions in the yellowish glow of electric bulbs. The mystery was dispelled together with the shadows.It was scared off by the frank indifference of the feeble lighting. The round, wide-open granite eyes of my mysterious acquaintances looked vacant and stupid in that orange-yellow light. Just as, in the blinding and false electrical light of common sense, everything about them seemed absurd. But all it takes is for a bulb to blow, or for the dynamo at the power-station to hiccup, and you are completely at the mercy of dark, latent forces and ways of thinking. The alternation of radiant lighting and periods of darkness allows you, as your imaginings develop, to go on fairy-tale wander ings down mysterious paths of art, like those we went down at the start, through galleries where the chiaroscuro on the bodies of the upright stone monsters moved towards us like Rembrandt’s ‘Night W atch’, but without the beards, whiskers, smiling eyes, or the fine headwear and scarves of the Flemish guardians of order. Museums should really be visited at night, and alone.

Mexico has an amazing effect on most people. I think that is because, wherever you look, the whole coun try seems to have just risen from the two oceans that wash her shores—everywhere she seems to be in a state of ‘coming into be ing’. In that particular dynamic condition that we contrast with the static notion of ‘being’. We know about this mostly from books. This complex notion about dynamic ‘coming into being’ means next to nothing to plodding minds.

What is so amazing about Mexico is the vivid sense that there you can experience things which you only know about otherwise from books and philosophical conceptions opposed to meta physics. I imagine that when the world was in its infancy it was full of exactly the same supremely indifferent laziness, coupled with the creative potential of those lagoons and plateaux, deserts and un dergrowth; pyramids you might expect to explode like volcanoes; palms reaching out to the blue vault of heaven; turtles swimming to the surface not from the bottom of creeks and inlets, but from the depths of oceans that are contiguous with the earth’s core.

People who have been to Mexico greet each other like brothers. For people who have been to Mexico catch the Mexican fever. Anyone who has ever seen the Mexican plains has only to close his eyes to picture something like the Garden of Eden; of course—Eden was not somewhere between the Tigris and Euphrates, but here, somewhere between the Gulf of Mexico and Tehuantepec! And this despite the mangy curs licking the dirty cooking pots with food, the universal graft and exasperating irresponsibility of incorrigible sloth, the terrible social injustices and rampantly ar bitrary actions of the police force, and agelong backwardness, which coexist alongside highly sophisticated forms of social exploitation.

Time leaches this tragic sediment from memory and, although it remains ineradicable in the consciousness, grains of pure gold are left in one’s emotions: the gold of the Mexican dawns and sunsets, the garments of the single madonnas and the columns of carved figures crowding out the altar decorations in a frozen multitude, the inlay work on rifles and embroidery on the sombreros of the charros and dorados, the stitching on the matadors’ capes, the warm bronze of pensive faces, and the succulent fruit with unheard-of names hanging down beneath the dark green, bluish or light grey foliage . . .

We know that our feelings, our consciousness and our frames of reference reflect the real world about us.