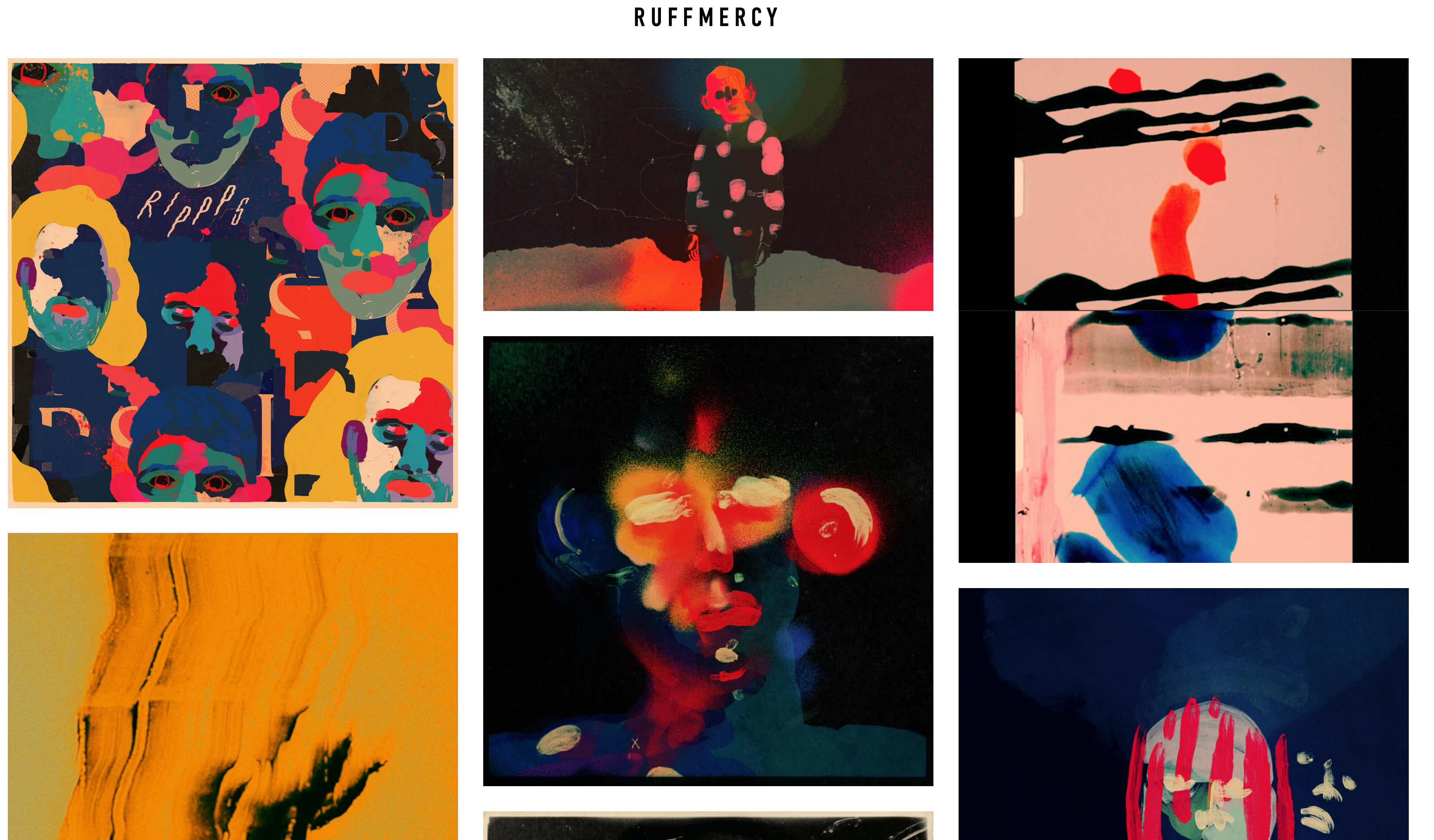

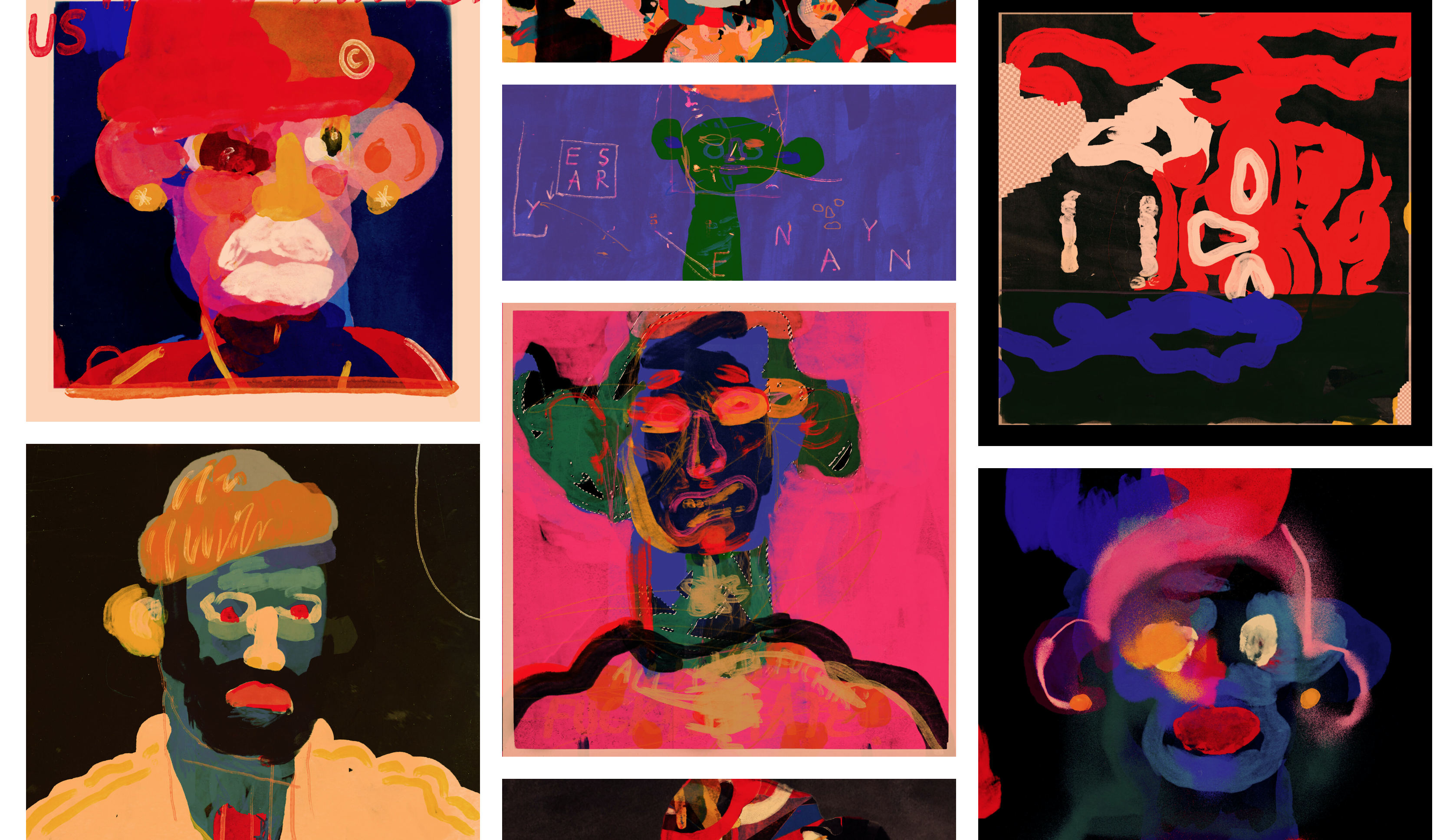

Chroma/Cerebellum 1988 2049

American Ocean, Russian Heartland, Chinese Century - a journey into the Cold War colours of the New Silk Road and a future for the New Silk Soul (一带一路 魂)

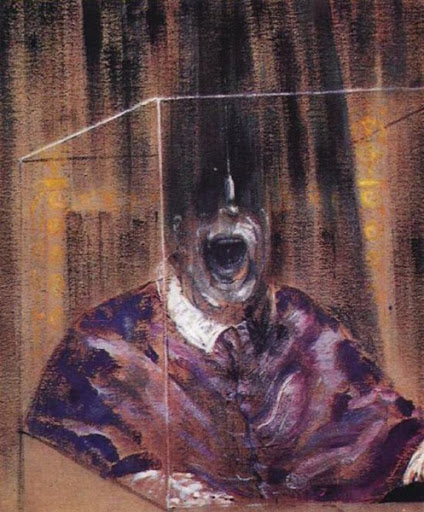

radial scream

“Listen,” Hilarius said after awhile, “have I seemed to you a good enough Freudian? Have I ever deviated seriously?”

“You made faces now and then,” said Oedipa, “but that’s minor.”

His response was a long, bitter laugh. Oedipa waited. “I tried,” the shrink behind the door said, “to submit myself to that man, to the ghost of that cantankerous Jew. Tried to cultivate a faith in the literal truth of everything he wrote, even the idiocies and contradictions. It was the least I could have done, nicht wahr? A kind of penance.”

“And part of me must have really wanted to believe

—like a child hearing, in perfect safety, a tale of horror

—that the unconscious would be like any other room, once the light was let in. That the dark shapes would resolve only into toy horses and Biedermeyer furniture. That therapy could tame it after all, bring it into society with no fear of its someday reverting. I wanted to believe, despite everything my life had been. Can you

imagine?”

She could not, having no idea what Hilarius had done before

“showing up in Kinneret. Far away she now heard sirens, the electronic kind the local cops used, that sounded like a slide-whistle being played over a PA. system. With linear obstinacy they grew louder.

“Yes, I hear them,” Hilarius said. “Do you think anyone can protect me from these fanatics? They walk through walls. They replicate: you flee them, turn a corner, and there they are, coming for you again.”

“Do me a favor?” Oedipa said. “Don’t shoot at the cops, they’re on your side.”

“Your Israeli has access to every uniform known,” Hilarius said. “I can’t guarantee the safety of the ‘police.’ You couldn’t guarantee where they’d take me if I surrendered, could you.”

“She heard him pacing around his office. Unearthly siren-sounds converged on them from all over the night. “There is a face,” Hilarius said, “that I can make. One you haven’t seen; no one in this country has. I have only made it once in my life, and perhaps today in central Europe there still lives, in whatever vegetable ruin, the young man who saw it. He would be, now, about your age. Hopelessly insane. His name was Zvi. Will you tell the ‘police,’ or whatever they are calling themselves tonight, that I can make that face again? That it has an

effective radius of a hundred yards and drives anyone unlucky enough to see it down forever into the darkened oubliette, among the terrible shapes, and secures the hatch irrevocably above them? Thank you.”

The sirens had reached the front of the clinic. She heard car doors slamming, cops yelling, suddenly a great smash as they broke in. The office door opened then. Hilarius grabbed her by the wrist, pulled her inside, locked the door again.”

“So now I’m a hostage,” Oedipa said.

“Oh,” said Hilarius, “it’s you.”

“Well who did you think you’d been——”

“Discussing my case with? Another. There is me, there are the others. You know, with the LSD, we’re finding, the distinction begins to vanish. Egos lose their sharp edges. But I never took the drug, I chose to remain in relative paranoia, where at least I know who I am and who the others are. Perhaps that is why you also refused to participate, Mrs Maas?” He held the rifle at sling arms and beamed at her. “Well, then. You were supposed to deliver a message to me, I assume. From them. What were you supposed to say?”

Oedipa shrugged. “Face up to your social responsibilities,” she suggested. “Accept the reality principle. You’re outnumbered and they have superior firepower.”

“Ah, outnumbered. We were outnumbered there too.” He watched her with a coy look.

“Where?”

“Where I made that face. Where I did my internship.”

She knew then approximately what he was talking about, but to narrow it said, “Where,” again.

“Buchenwald,” replied Hilarius. Cops began hammering on the office door.

“He has a gun,” Oedipa called, “and I’m in

here.” (The Crying of Lot 49)

Note the Munchen Scream was painted under the effects of coronavirus, Spanish influenza 1918, Munch’s horror, the radial outside, the siniy transmission.

Jarman staring at the ceiling under the effects of latechemo, reds, crystallising above and there’s a Maas like sense“was part of his duty, wasn’t it, to bestow life on what had persisted, to try to be what Driblette was, the dark machine in the centre of the planetarium, to bring the estate into pulsing stelliferous Meaning, all in a soaring dome around him? Mondaugen-like, sferic, and SPHERA, sphera is sferic

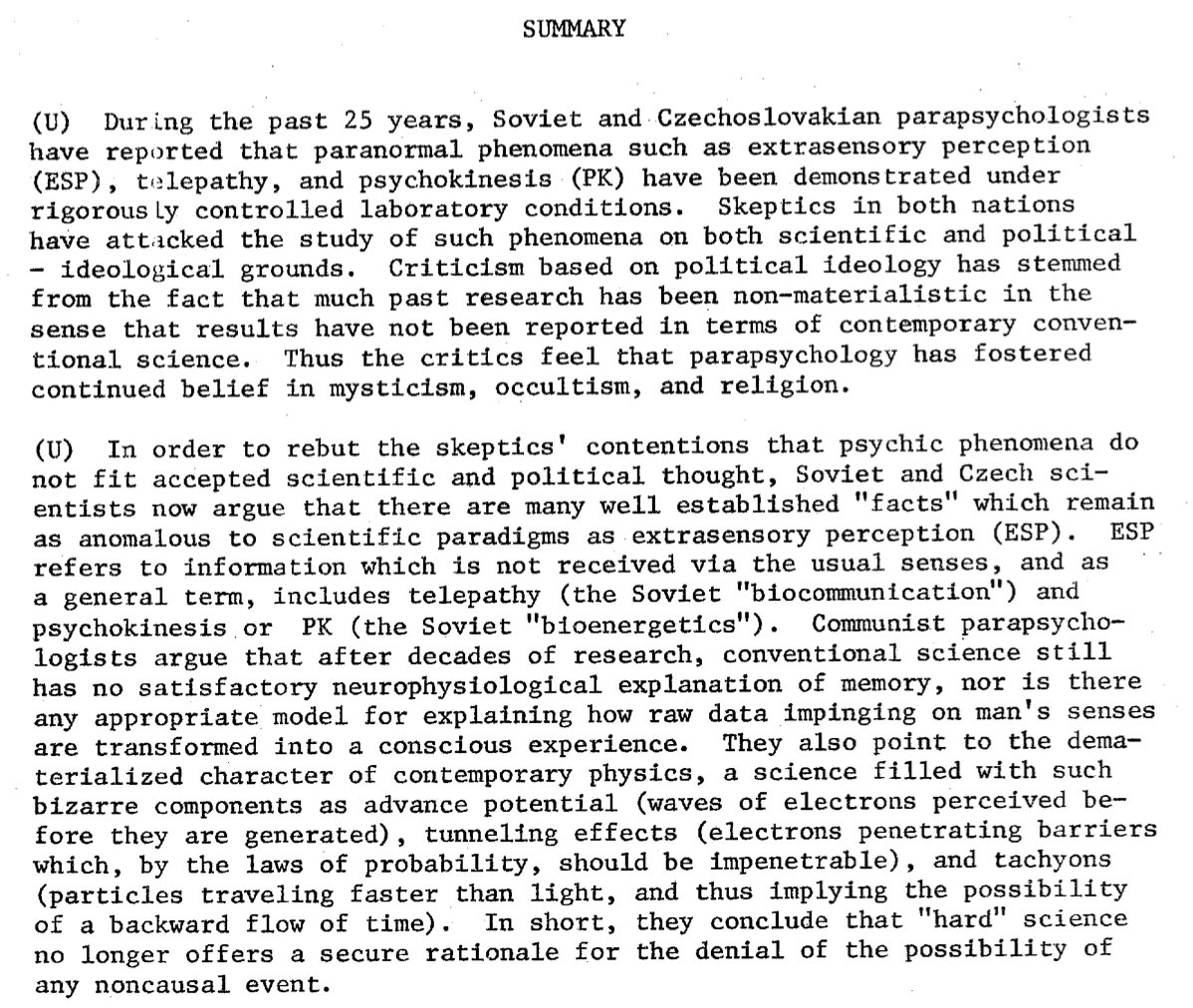

Transmission-0. Sphera as Rashomonic/Goluboynetic Massumian Incident exhibiting Bipolarised Psychokinetic Effects

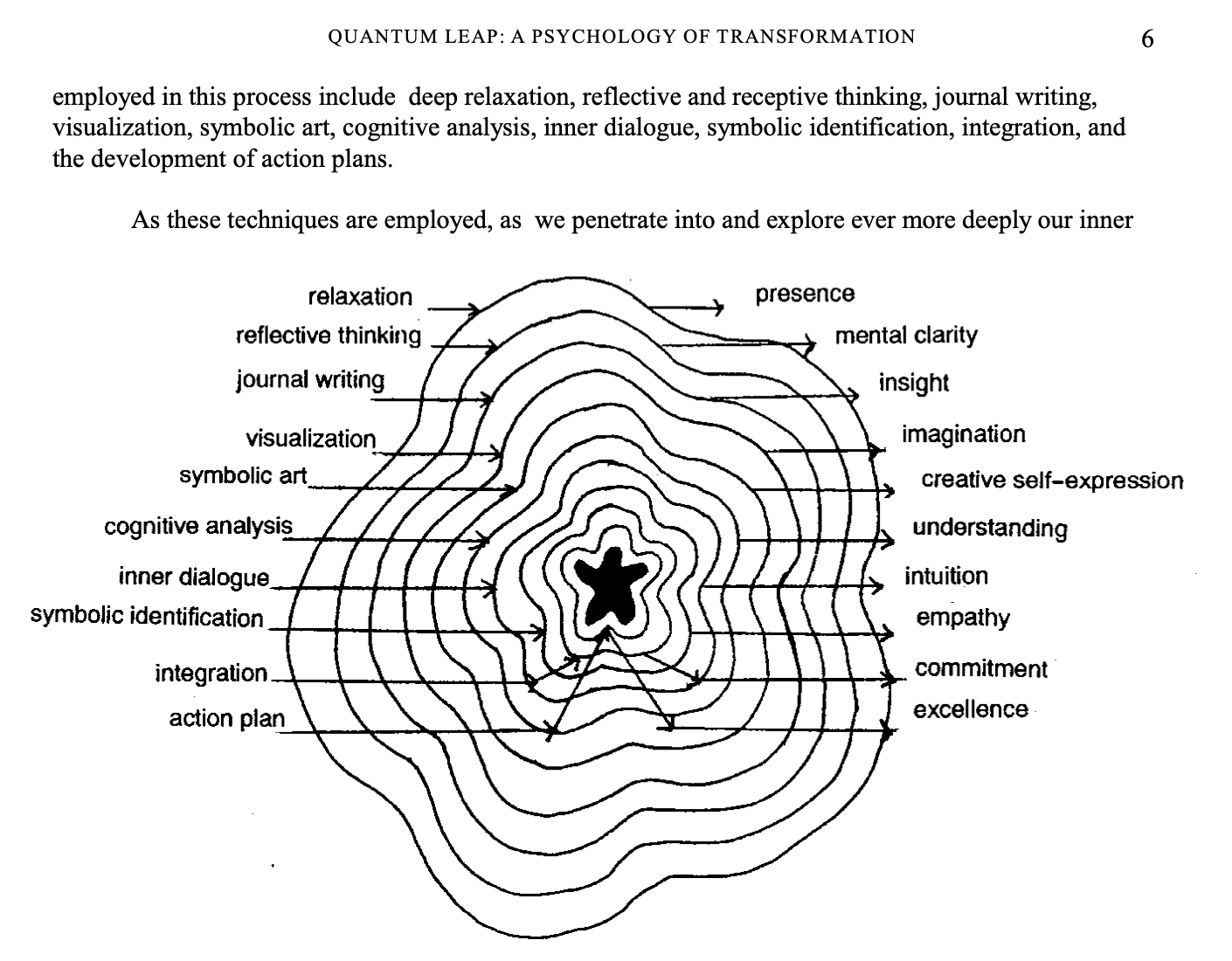

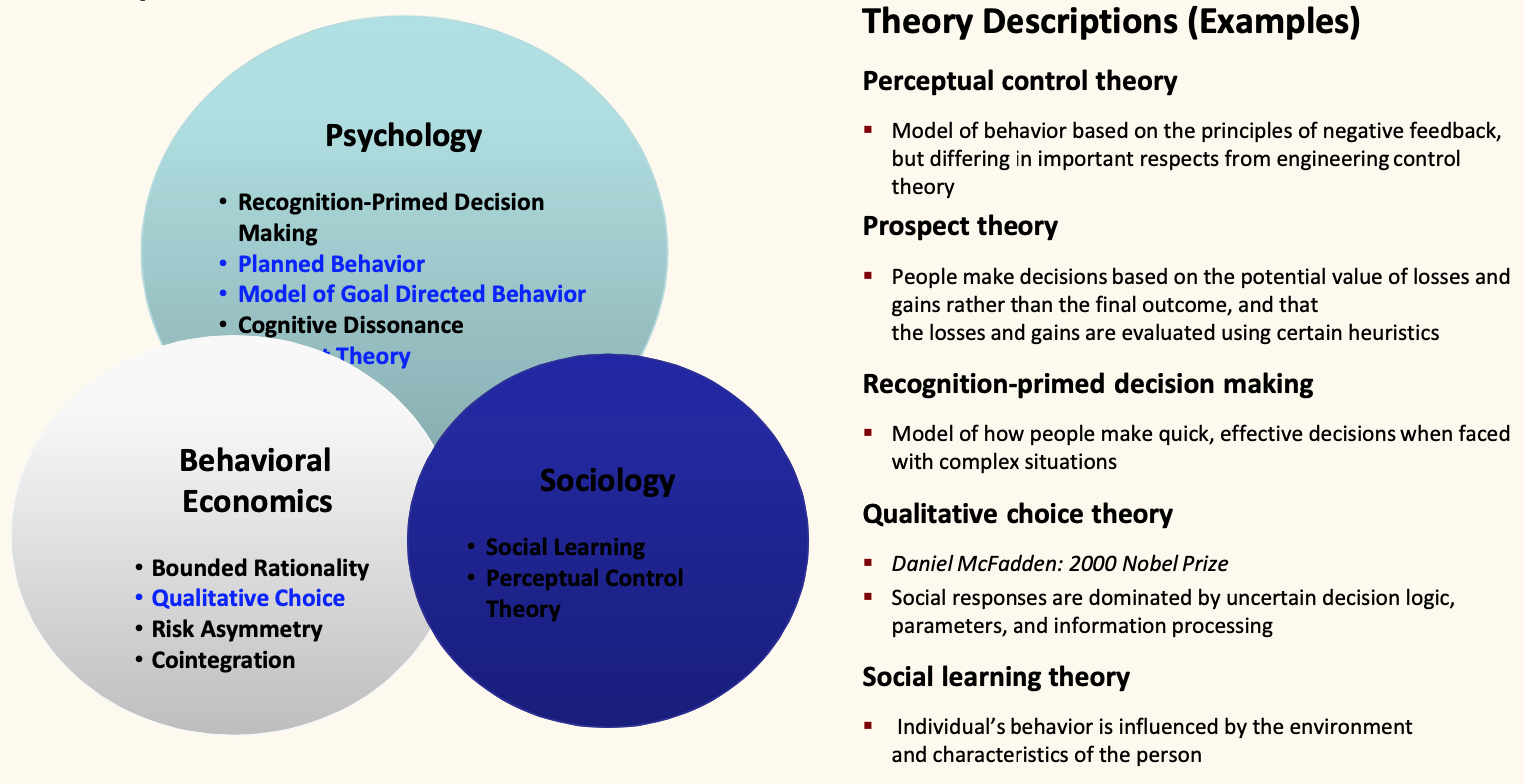

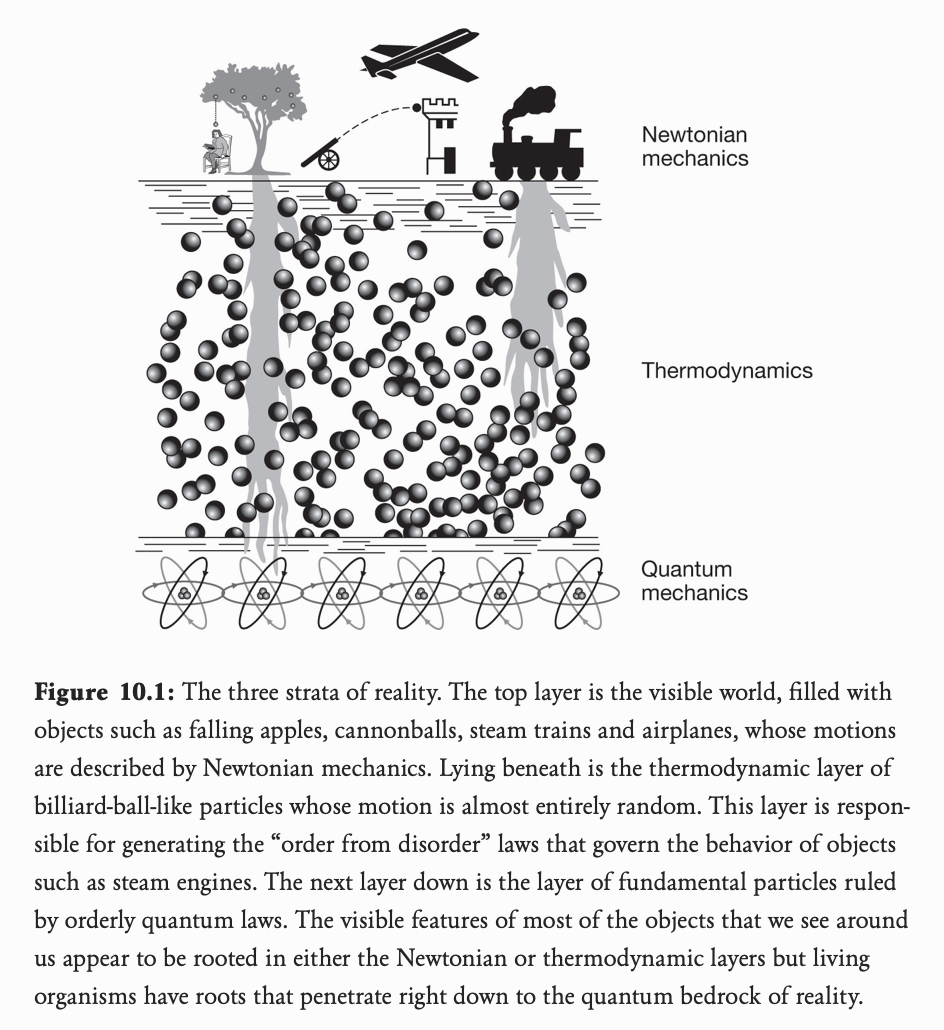

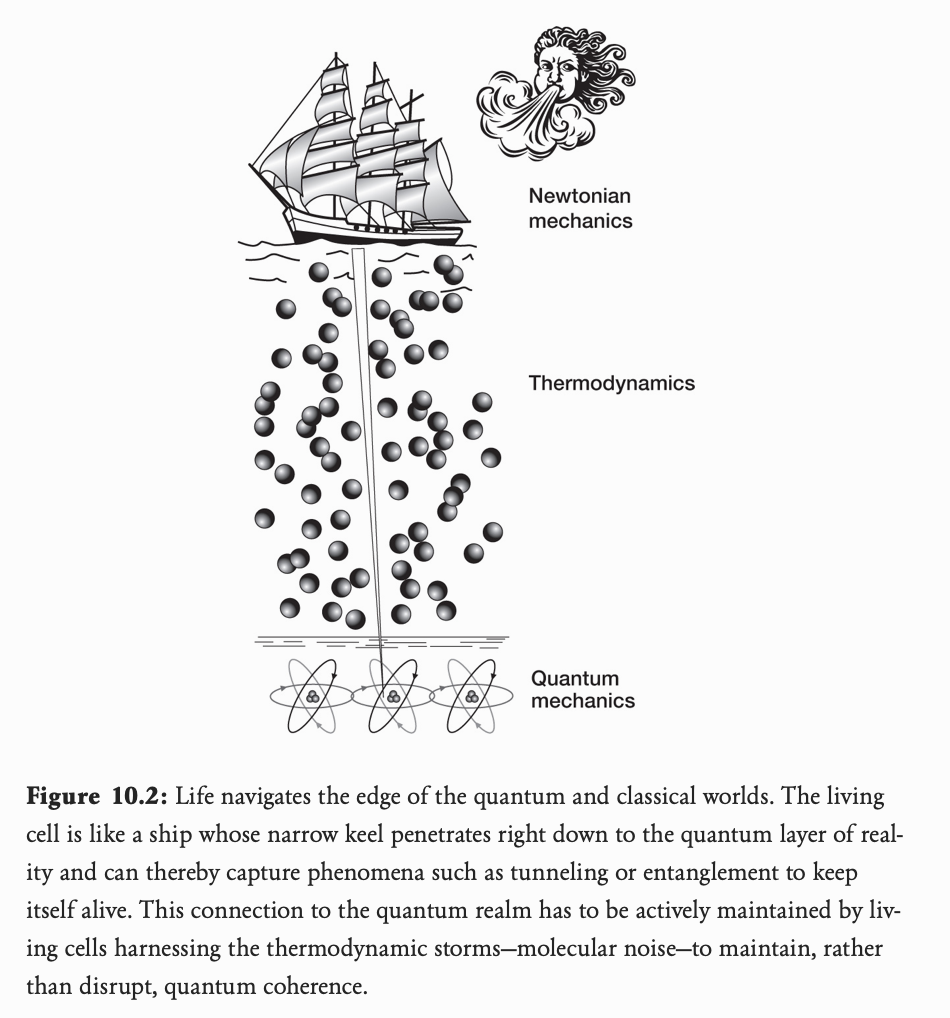

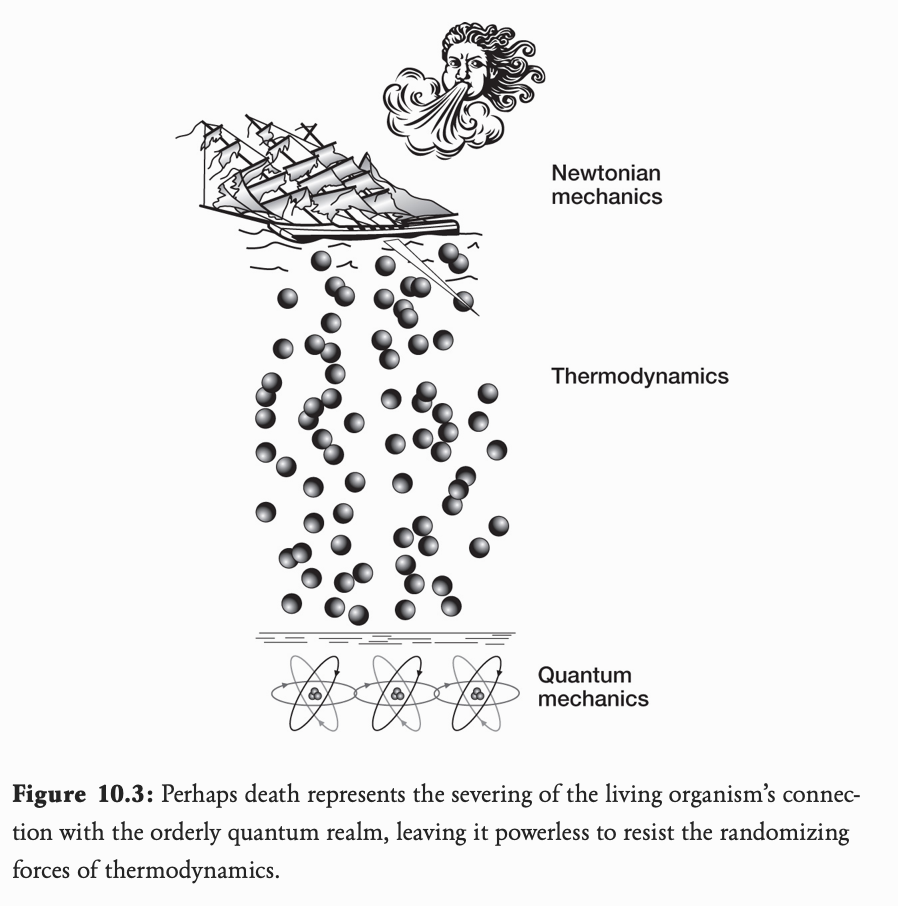

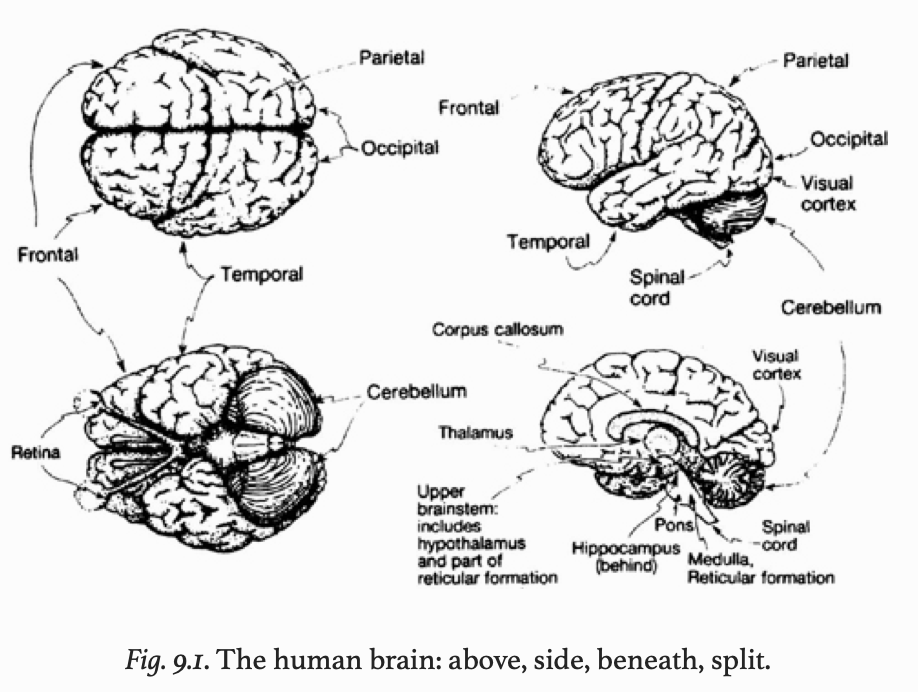

Euphoris, neural forestry, touch entropy, heat but information increasing saturating, Phrenis Schizia waving at the platform ululating 30 years distant light. Points, lines, beams ego light seep laserous, Lazarus. Decision happens: affectively-systemically, in the nonconscious processual autonomous zone where mutually exclusive states come together. The event decides, as it happens. At the decisive moment, the self is no more in a state of determinate activity than it is in a cognitive state. It is absorbed in a readiness potential that is intensely overdetermined, holding, Luhmann says, “a whole range of possible differences” in “sub-threshold latency” (Luhmann 1979, 73). The whole range of potentials are in it together, in their difference. They are in a state of mutual inclusion, on the verge, poised toward the collapse destined to resolve the overdetermination of the and-both into this-not-that determinate effect, registrable in a calculus of risk and probability: from intensity to statistic. “The nonconscious “sub-threshold latency,” churning with the intensity of a mutually inclusive range of potentials, in co-motional intensity, deserves a name of its own: bare activity. No amount of sophisticated modeling will expunge the hard economic fact that under complex conditions of uncertainty rational choice and affect-driven intuition enter a zone of indistinction. To put it another way, “rationality about the unknown requires emotions” (Pixley 2004, 30). This points to an experiential plasticity that belies any notion of an underlying principle of personal preference as having the sovereign power to determine action. What are experienced as satisfying qualities of experience are surprisingly open to situational conditioning. ” Situational Conditioning as Geography. Interpreted in light of the first experiment, the plasticity of moral conviction shown in the second experiment appears as a higher-order recapitulation of a perceptual dynamic. The phenomenon of choice blindness points to a tendency toward fabulation built into perceptual experience. Or more precisely: built into the temporality of our perceptual experience. The self-evidence of our present perception does not stand the test of time. Our memory plays tricks on us. It is becoming increasingly accepted that a memory is not reproduced. Rather, it is regenerated. A memory is always an event, never a representation. The event of memory varies according to the conditions under which it is produced. Personal memory is an evolving dynamic system that is predicated not on reproduction but on re-creation. In the vocabulary of cognitive science, memory is by nature “reconstructive.” This means that the person we are as a function of our memories is self-re-creating. The fabulatory element of perception as it varies over time is a creative factor in life. In its absence, the individual would be an ambulant repetition-compulsion, shackled to a bedrock of past preferences and principles. What would possess me to forgo my tried and true satisfactions? The only way for change to occur would be through the imposition of modified behaviors from without, either in the form of brute conformal force, or through the disciplinary inculcation of norms meant to be interiorized in such as way as to foster conformal behavior even in the absence of force. Priming operates less through stimulus-response than through cues whose force is situational. Priming addresses threshold postures (presuppositions) orienting a participant’s entry into the situation, plus the associated tendencies that carry the orientation forward through the encounter. Accordingly, it does not exercise the same kind of power as normative-disciplinary mechanisms (of which both traditional forms of conditioning are highly distilled forms). It is of the utmost significance that priming depends, on the one hand, on the individual’s susceptibility to its own tendential infra-churnings and, on the other, on its openness to the situation—the individual’s bipolar affectability. Priming operationalizes the cross-sensitivity between the infra- and macropoles

“So does my husband,” she said. “I understand.” John Nefastis beamed at her, simpatico, and brought out his Machine from a workroom in back. It looked about the way the patent had described it. “You know how this works?” Stanley gave me a kind of rundown.” He began then, bewilderingly, to talk about something called entropy. The word bothered him as much as “Trystero” bothered Oedipa. But it was too technical for her. She did gather that there were two distinct kinds of this entropy. One having to do with heat-engines, the other to do with communication. The equation for one, back in the ‘3o’s, had looked very like the equation for the other. It was a coincidence. The two fields were entirely unconnected, except at one point: Maxwell’s Demon. As the Demon sat and sorted his molecules into hot and cold, the system was said to lose entropy. But somehow the loss was offset by the information the Demon gained about what molecules were where. “Communication is the key,” cried Nefastis. “The Demon passes his data on to the sensitive, and the sensitive must reply in kind. There are untold billions of molecules in that box. The Demon collects data on each and every one. At some deep “psychic level he must get through. The sensitive must receive that staggering set of energies, and feed back something like the same quantity of information. To keep it all cycling. On the secular level all we can see is one piston, hopefully moving. One little movement, against all that massive complex of information, destroyed over and over with each power stroke.” “Help,” said Oedipa, “you’re not reaching me.” “Entropy is a figure of speech, then,” sighed Nefastis, “a metaphor. It connects the world of thermo-dynamics to the world of information flow. The Machine uses both. The Demon makes the metaphor not only verbally graceful, but also objectively true.” But what,” she felt like some kind of a heretic, “if the Demon exists only because the two equations look alike? Because of the metaphor?” Nefastis smiled; impenetrable, calm, a believer. “He existed for Clerk Maxwell long before the days of the metaphor.”

Transmission-1. The Black Sea. China, the U.S. and I, I.F. , dancing in the Roche limit of a former Soviet moon

I.F. Transmission 1. The Black Sea.

I now know why Jean Baudrillard called them cool memories. Or why W.G. Sebald fixated on the Roche effect – those ice crystals of a former moon that strayed too closed to Saturn and were destroyed by its tidal effect. Franz Mesmer the strange German doctor-astronomer called those Roche forces that work on us in sleep or fading self awareness the floodabilities, flutbarkeiten. Memory is satelittic, fragmentary, a fall into pixelline heat, Always decompressing, cooling. Just as the past is not a static but Roche flickers caught on the tide In June 2018, I set off with three people across the New Silk Roads, the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt of China’s 1 trillion infrastructure project stretching through Central Asia to Europe. We began on the edge, under the hothouse of Russian pressure Anaklia:

Georgia – Poti Free Industrial Zone, Anaklia Development Consortium and Deep Water Port (26 – 30 June) || Azerbaijan – Baku International Sea Trade Port Alyat (Phase II) (01 – 07 July 2018) || Kazakhstan – Aktau Economic Hub (08 – 12 July 2018) || Kyrgyzstan – Kyrgyzstan-China gas pipeline and Bishkek Power Station (13 – 16 July 2018) || Kazakhstan – Almaty and Khorgos Gateway and Dry Port (16 – 21 July 2018) || Xinjiang International Logistics Park (21 – 24 July 2018) || Lanzhou New Area Free Trade Zone (25 – 27 July 2018); || Xi’an International Trade and Logistics Park (27 – 29 July 2018); || Chengdu Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone (29 – 30 July 2018); Chongqing-Chengdu city cluster (31 July – 01 August 2018) ||Yiwu Wholesales Market (02 August – 04 August 2018); || Shanghai (04 August – 06 August 2018); || Beijing (06 – 10 August 2018); and || Hong Kong (10 August – 15 August 2018). We interviewed experts, in suits, I took photos, videos, I came home and started a job at Forensic Architecture, a research agency undertaking media and architectural investigations in conflict zones. I let the trip decompress, as summers do, into cool freight. At the beginning of 2019, I bought a website domain, blip.land, the blip I imagined was that transience of the passage, a blip on a radar, and yet the concrete of the opinion of a place we form. Blip is that world becoming distant, becoming fuselage to the gait. Crank up the heat in the hothouse of misunderstanding. Life is depth in black sea, death is blip, stay on the machine. Memory is satelittic, but we forget where we were when they were launched.

Where were you when the engines flooded kerosene and the clouds exploded grey? Long march 5 becoming godly red hue, streaking the angel line, contrails burning up, on a cornea, an iris, the controlled trauma, becoming cool memory in blinding heat. According to Zinchenko, Russia is a space where the horizontal and the vertical, expansiveness and outer space, intersect. America controlling the skies, the ocean, always a strong horizontalism to the American psyche – to push the envelope, to convert hearts, to eulogise, to evangelise, given wings on the oceanic currents, the airwaves. The Belt and Road is not so much horizontal, as a sensoria of speed, transmission, signal into the sky and the fragments that sink satellitic into the psyche, the pixelline blothouse, the Black Sea.

The New Silk Road [sic] New Space Race

China’s Pursuit of Space Power Status and Implications for the United States (Alexander Bowe, US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, April 2019): https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/fi… The Changing Dynamics of Twenty First Century Space Power (James Clay Moltz, 2019): https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Port… China in Space: The Great Leap Forward (Brian Harvey 2019):

https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=e…

Transmission-2. The Bicameral Mind of a Cold War Blue

August 18, 1988, Louisiana Superdome, New Orleans | George H.W. Bush acceptance speech as the Republican presidential candidate at the 1988 Republican National Convention.

My approach this evening is, as Sergeant Joe Friday used to say, “Just the facts, ma’m.” After all, the facts are on our side. I seek th-e presidency for a single purpose, a purpose that has motivated millions of Americans across the years and the ocean voyages. I seek the presidency to build a better America. It is that simple – and that big. I am a man who sees life in terms of missions – missions defined and missions completed. When I was a torpedo bomber pilot they defined the mission for us. Before we took off we all understood that no matter what, you try to reach the target. There have been other missions for me – Congress, China, the CIA. But I am here tonight – and I am your candidate – because the most important work of my life is to complete the mission we started in 1980. How do we complete it? We build it. The stakes are high this year and the choice is crucial, for the differences between the two candidates are as deep and wide as they have ever been in our long history. Not only two very different men, but two very different ideas of the future will be voted on this election day. What it all comes down to is this: My opponent’s view of the world sees a long slow decline for our country, an inevitable fall mandated by impersonal historical forces. But America is not a decline. America is a rising nation. He sees America as another pleasant country on the UN roll call, somewhere between Albania and Zimbabwe. I see America as the leader – a unique nation with a special role in the world. This has been called the American Century, because in it we were the dominant force for good in the world. We saved Europe, cured polio, we went to the moon, and lit the world with our culture. Now we are on the verge of a new century, and what country’s name will it bear? I say it will be another American century. Our work is not done – our force is not spent. There are those who say there isn’t much of a difference this year. But America, don’t let ’em fool ya. Two parties this year ask for your support. Both will speak of growth and peace. But only one has proved it can deliver. Two parties this year ask for your trust, but only one has earned it. Eight years ago I stood here with Ronald Reagan and we promised, together, to break with the past and return America to her greatness. Eight years later look at what the American people have produced: the highest level of economic growth in our entire history – and the lowest level of world tensions in more than fifty years.

[…] But let’s be frank. Things aren’t perfect in this country. There are people who haven’t tasted the fruits of the expansion. I’ve talked to farmers about the bills they can’t pay. I’ve been to the factories that feel the strain of change. I’ve seen the urban children who play amidst the shattered glass and shattered lives. And there are the homeless. And you know, it doesn’t do any good to debate endlessly which policy mistake of the ’70’s is responsible. They’re there. We have to help them. But what we must remember if we are to be responsible – and compassionate – is that economic growth is the key to our endeavors. I want growth that stays, that broadens, and that touches, finally, all Americans, form the hollows of Kentucky to the sunlit streets of Denver, from the suburbs of Chicago to the broad avenues of New York, from the oil fields of Oklahoma to the farms of the great plains. Can we do it? Of course we can. We know how. We’ve done it. If we continue to grow at our current rate, we will be able to produce 30 million jobs in the next eight years. We will do it – by maintaining our commitment to free and fair trade, by keeping government spending down, and by keeping taxes down. Our economic life is not the only test of our success, overwhelms all the others, and that is the issue of peace. One issue Look at the world on this bright August night. The spirit of Democracy is sweeping the Pacific rim. China feels the winds of change. New democracies assert themselves in South America. One by one the unfree places fall, not to the force of arms but to the force of an idea: freedom works. We have a new relationship with the Soviet Union. The INF treaty – the beginning of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan – the beginning of the end of the Soviet proxy war in Angola, and with it the independence of Namibia. Iran and Iraq move toward peace. It is a watershed. It is no accident. It happened when we acted on the ancient knowledge that strength and clarity lead to peace – weakness and ambivalence lead to war. Weakness and ambivalence lead to war. Weakness tempts aggressors. Strength stops them. I will not allow this country to be made weak again. The tremors in the Soviet world continue. The hard earth there has not yet settled. Perhaps what is happening will change our world forever. Perhaps what is happening will change our world forever. Perhaps not. A prudent skepticism is in order. And so is hope. Either way, we’re in an unprecedented position to change the nature of our relationship. Not by preemptive concession – but by keeping our strength. Not by yielding up defense systems with nothing won in return – but by hard cool engagement in the tug and pull of diplomacy. My life has been lived in the shadow of war – I almost lost my life in one. I hate war. I love peace. We have peace. And I am not going to let anyone take it away from us. Our economy is strong but not invulnerable, and the peace is broad but can be broken. And now we must decide. We will surely have change this year, but will it be change that moves us forward? Or change that risks retreat?

Transmission-3a. American Ocean, Russian Heartland: summer, 1962 and the New Silk Roads, children of the atom.

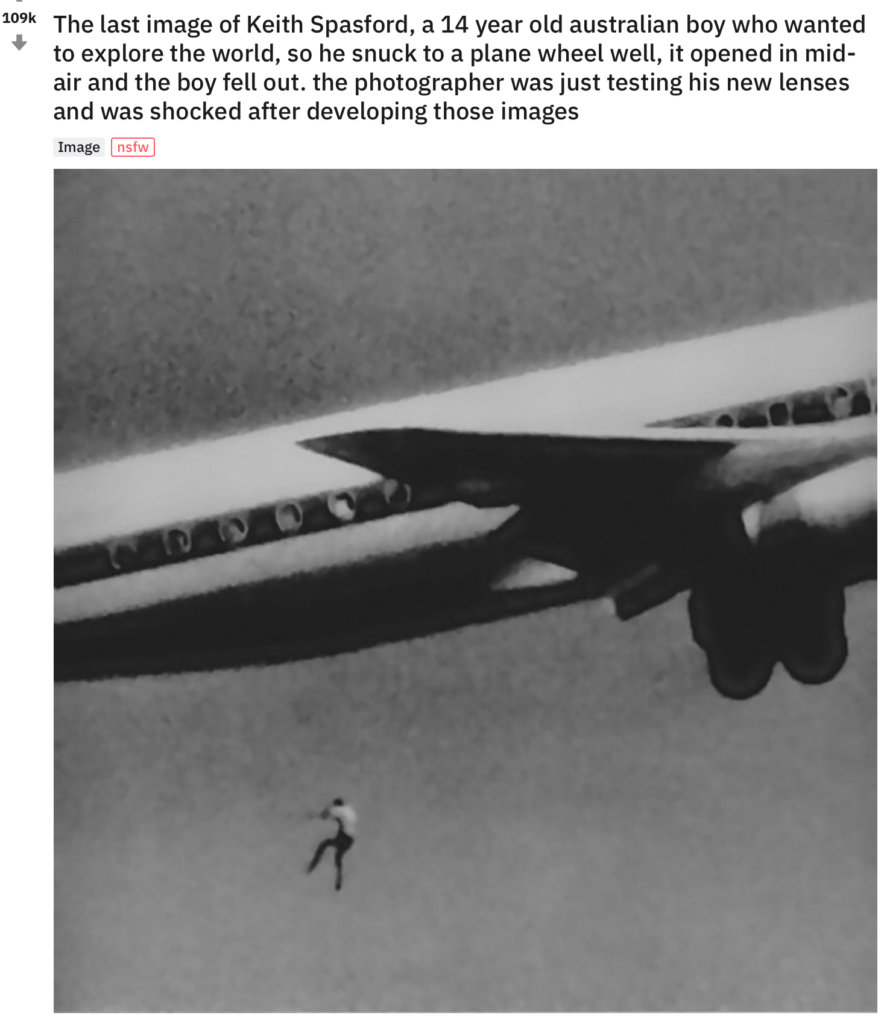

He’s riding a U2 stealth plane at 70,000ft over far eastern Soviet reds in a telluric sunrise / Pacific blue washing into the secret arc / Over Semipalatinsk test site in cartridges loaded / dreaming of the atom / fissile heat / throwing up soviet dirt in the Kazakh desert / He sights the colours change deep down below / To landlock yellows, reds and greens / Marian back home, cooking in colour television, / He senses his part in some way abstract / To the atomic summer of 1962 / Slamming into the Siberian coastline / the power of the American ocean gifting light / To the dark regions of this land unfree / Under the stealth hum of the engines / The drowned out clicks of black film cartidges loading.

1960 U-2 incident

On 1 May 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Air Defence Forces while performing photographic aerial reconnaissance deep into Soviet territory. The single-seat aircraft, flown by pilot Francis Gary Powers, was hit by an S-75 Dvina (SA-2 Guideline) surface-to-air missile and crashed near Sverdlovsk (today’s Yekaterinburg). Powers parachuted safely and was captured. Initially, the US authorities acknowledged the incident as the loss of a civilian weather research aircraft operated by NASA, but were forced to admit the mission’s true purpose when a few days later the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and parts of the U-2’s surveillance equipment, including photographs of Soviet military bases taken during the mission. The incident occurred during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower and the premiership of Nikita Khrushchev, around two weeks before the scheduled opening of an east–west summit in Paris. It caused great embarrassment to the United States and prompted a marked deterioration in its relations with the Soviet Union, already strained by the ongoing Cold War On 28 April 1960, a U.S. Lockheed U-2C spy plane, Article 358, was ferried from Incirlik Air Base in Turkey to the US base at Peshawar airport by pilot Glen Dunaway. Fuel for the aircraft had been ferried to Peshawar the previous day in a US Air Force C-124 transport. A US Air Force C-130 followed, carrying the ground crew, mission pilot Francis Powers, and the back up pilot, Bob Ericson. On the morning of 29 April, the crew in Badaber was informed that the mission had been delayed one day. As a result, Bob Ericson flew Article 358 back to Incirlik and John Shinn ferried another U-2C, Article 360,[7] from Incirlik to Peshawar. On 30 April, the mission was delayed one day further because of bad weather over the Soviet Union.[6] The weather improved and on 1 May, 15 days before the scheduled opening of the east–west summit conference in Paris, Captain Powers, flying Article 360, 56–6693 left the base in Peshawar on a mission with the operations code word GRAND SLAM[8] to overfly the Soviet Union, photographing targets including the ICBM sites at the Baikonur Cosmodrome and Plesetsk Cosmodrome, then land at Bodø in Norway. At the time, the USSR had six ICBM launch pads, two at Baikonur and four at Plesetsk.[9] Mayak, then named Chelyabinsk-65, an important industrial center of plutonium processing, was another of the targets that Powers was to photograph.[10] A close study of Powers’s account of the flight shows that one of the last targets he overflew, before being shot down, was the Chelyabinsk-65 plutonium production facility.[11] The U-2 flight was expected, and all units of the Soviet Air Defence Forces in the Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Siberia, Ural, and later in the USSR European Region and Extreme North, were placed on red alert. Soon after the plane was detected, Lieutenant General of the Air Force Yevgeniy Savitskiy ordered the air-unit commanders “to attack the violator by all alert flights located in the area of foreign plane’s course, and to ram if necessary”.[12] Because of the U-2’s extreme operating altitude, Soviet attempts to intercept the plane using fighter aircraft failed. The U-2’s course was out of range of several of the nearest SAM sites, and one SAM site even failed to engage the aircraft since it was not on duty that day. The U-2 was eventually brought down near Kosulino, Ural Region, by the first of three SA-2 Guideline (S-75 Dvina) surface-to-air missiles[13] fired by a battery commanded by Mikhail Voronov.[6] The SA-2 site had been previously identified by the CIA, using photos taken during Vice President Richard Nixon’s visit to Sverdlovsk the previous summer.[14][15] Powers bailed out but neglected to disconnect his oxygen hose first and struggled with it until it broke, enabling him to separate from the aircraft. After parachuting safely down onto Russian soil, Powers was quickly captured.[12] Powers carried with him a modified silver dollar which contained a lethal, shellfish-derived saxitoxin-tipped needle, but he did not use it.[16] Upon his capture, Gary Powers told his Soviet captors what his mission had been and why he had been in Soviet airspace. He did this in accordance with orders that he had received before he went on his mission.[41] Powers pleaded guilty and was convicted of espionage on 19 August and sentenced to three years imprisonment and seven years of hard labor. He served one year and nine months of the sentence before being exchanged for Rudolf Abel on 10 February 1962.[3] The exchange occurred on the Glienicke Bridge connecting Potsdam, East Germany, to West Berlin.[51]

April 30 2016. A Russian nuclear submarine, Severodvinsk, has carried out firing drills in the Barents Sea, successfully striking a coastal target in the Arctic with the latest Kalibr cruise missile from a submerged position. The crew of the latest multipurpose nuclear submarine of the Northern Fleet, Project 885 Severodvinsk, successfully launched the missile from the Barents Sea, the Russian military said in a statement. The missile hit its target in the Arkhangelsk region “with high accuracy”, the statement added. The strike was conducted as part of wider navy combat drills in the area. The ministry also noted that Severodvinsk, which sailed to sea earlier this week, has carried out a number of other drills within the winter framework training exercises of Russia’s Northern Fleet. Russian Kalibr missiles were also tested on the Caspian Flotilla during week-long drills that involved some 20 vessels and concluded on Friday. “A strike group of the flotilla has conducted firing drills using naval practice targets and hit them successfully,” the press service said. Ships with the Russian Navy’s Caspian Flotilla fired off 3M-14 submarine-launched cruise missiles (SLCM) for the first time on Islamic State targets in Syria on October 7 and November 20. Ever since the debut, the Kalibr became one of the main perceived threats to US security. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) said in December that it“is profoundly changing [Russia’s] ability to deter, threaten or destroy adversary targets.” With a range of roughly of 2,000 km, the supersonic 3M-54 Kalibr missile is small enough to be carried by submarines and small warships. Furthermore the missile is capable of carrying both a conventional or nuclear warhead and is able to penetrate the enemy’s missile defense systems thus changing the calculus of the reach and effectiveness of smaller navy ships.

Transmission-3b. The Man in the High Castle (Philip K. Dick, 1962)

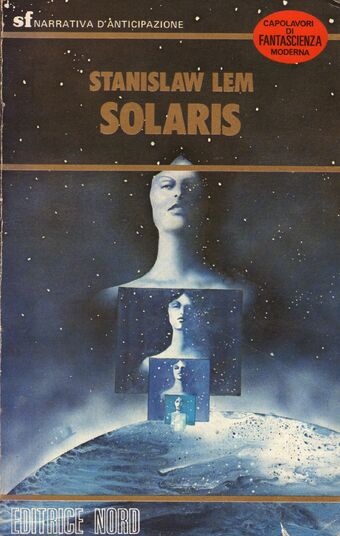

Transmission-3c. Solaris (Stanislaw Lem, 1961)

The planet orbits two suns: a red sun and a blue sun. For 45 years after its discovery, no spacecraft had visited Solaris. From where I was, I could see only a part of the corridor encircling the laboratory. I was at the summit of the Station, beneath the actual shell of the superstructure; the walls were concave and sloping, with oblong windows a few yards apart. The blue day was ending, and, as the shutters grated upwards, a blinding light shone through the thick glass. Every metal fitting, every latch and joint, blazed, and the great glass panel of the laboratory door glittered with pale coruscations. I got up. The disc of the sun, reminiscent of a hydrogen explosion, was sinking into the ocean

Transmission-3d. The Three Body Problem (Liu Cixin, 2008)

And now, the Sun really was melting, its blood seeping into the deadly plane. This was the last sunset.

Transmission-4a. Alexander Dugin Shanghai Lectures (2018) Eurasianism 欧亚大陆

Eurasianism 欧亚大陆 Principles, Theories, Geopolitics 原则, 理论,地缘政治

Eurasia = geographical concept (Europe – small, Asia – big)

Eurasia = Land Power, Heartland of Mackinder (opposed to Sea Power and atlanticism)

Eurasia = Turan, Step’, nomadic part to the north from China, India, Persia, Greece

Eurasia = Russia as country

Eurasia = Russia as Empire, USSR, Post-Soviet space

Eurasia = Russia as civilization (slavo-turk, European/Asian)

Eurasia = Idea of unified diversity (Empire of Middle)

Eurasia = one pole of multipolar world

Extract from Last War of the World Island: The Geopolitics of Contemporary Russia (Dugin, 2015 pages 16-18)

The Russian Federation is in the Heartland. The historical structure of Russian society displays vividly expressed tellurocratic traits. Without hesitation, we should associate the Russian Federation, too, with a government of the land-based type, and contemporary Russian society with a mainly holistic society. The consequences of this geopolitical identification are global in scale. On its basis, we can make a series of deductions, which must lie at the basis of a consistent and fully-fledged Russian geopolitics of the future.

1. Russia’s geopolitical identity, being land-based and tellurocratic, demands strengthening, deepening, acknowledgement, and development. The substantial side of the policy of affirming political sovereignty, declared in the early 2000s by the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, consists in precisely this. Russia’s political sovereignty is imbued with a much deeper significance: it is the realization of the strategic project for the upkeep of the political-administrative unity of the Heartland and the (re)creation of the conditions necessary for Russia to act as the tellurocratic pole on a global scale. In strengthening Russia’s sovereignty, we strengthen one of the columns of the world’s geopolitical architecture; we carry out an operation, much greater in scale than a project of domestic policy concerning only our immediate neighbors, in the best case. Geopolitically, the fact that Russia is the Heartland makes its sovereignty a planetary problem. All the powers and states in the world that possess tellurocratic properties depend on whether Russia will cope with this historic challenge and be able to preserve and strengthen its sovereignty.

2. Beyond any ideological preferences, Russia is doomed to conflict with the civilization of the Sea, with thalassocracy, embodied today in the USA and the unipolar America-centric world order. Geopolitical dualism has nothing in common with the ideological or economic peculiarities of this or that country. A global geopolitical conflict unfolded between the Russian Empire and the British monarchy, then between the socialist camp and the capitalist camp. Today, during the age of the democratic republican arrangement, the same conflict is unfolding between democratic Russia and the bloc of the democratic countries of NATO treading upon it. Geopolitical regularities lie deeper than political-ideological contradictions or similarities. The discovery of this principal conflict does not automatically mean war or a direct strategic conflict. Conflict can be understood in different ways. From the position of realism in international relations, we are talking about a conflict of interests which leads to war only when one of the sides is sufficiently convinced of the weakness of the other, or when an elite is put at the head of either state that puts national interests above rational calculation. The conflict can also develop peacefully, through a system of a general strategic, economic, technological, and diplomatic balance. Occasionally it can even soften into rivalry and competition, although a forceful resolution can never be consciously ruled out. In such a situation the question of geopolitical security is foremost, and without it no other factors — modernisation, an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or the standard of living, and so forth — have independent significance. What is the point of our creating a developed economy if we will lose our geopolitical independence? This is not “bellicose,” but a healthy rational analysis in a realist spirit; this is geopolitical realism.

3. Geopolitically, Russia is something more than the Russian Federation in its current administrative borders. The Eurasian civilization, established around the Heartland with its core in the Russian narod, is much broader than contemporary Russia. To some degree, practically all the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) belong to it. Onto this sociological peculiarity, a strategic factor is superimposed: to guarantee its territorial security, Russia must take military control over the center of the zones attached to it, in the south and the west, and in the sphere of the northern Arctic Ocean. Moreover, if we consider Russia — a planetary tellurocratic pole, then it becomes apparent that its direct interests extend throughout the Earth and touch all the continents, seas, and oceans. Hence, it becomes necessary to elaborate a global geopolitical strategy for Russia, describing in detail the specific interests relating to each country and each region.

Transmission-4b. Chinese Nuclear Testing 1966.

Two Bombs, One Satellite (Chinese: 两弹一星; pinyin: Liǎngdàn Yīxīng) was an early nuclear and space project of the People’s Republic of China. Two Bombs refers to the atomic bomb (and later the hydrogen bomb) and the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), while One Satellite refers to the artificial satellite. China tested its first atomic bomb and hydrogen bomb in 1964 and 1967 respectively, and successfully launched its first satellite (DFH-1) in 1970.[1][2] 23 scientists involved in the project were awarded the Two Bombs and One Satellite Merit Award (Chinese: 两弹一星功勋奖章) in 1999.[3][4] In 2015, the Two Bombs, One Satellite Memorial Museum was opened on the Huairou campus of the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.[5]

28 December 1966 China conducts its fifth nuclear test. This boosted-fission atmospheric test is done with a tower-mounted device to confirm the design principles of a two-stage nuclear device. The explosive yield is between 300 kilotons and 500 kilotons of TNT. — John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 201, 244; Xiaoping Yang, Robert North and Carl Romney, “CMR Nuclear Explosion Database (Revision 3): CMR Technical Report CMR-00/16,” August 2000, www.rdss.info; US Army Space and Missile Defense Command Monitoring Research Program “Nuclear Explosion Database,” www.rdss.info.

27 October 1966 China conducts its fourth nuclear test. This atmospheric test uses the Dongfeng-2, a medium-range ballistic missile, which is launched from Shuangchengzi to Lop Nur. The explosive yield is between 12 kilotons and 30 kilotons of TNT. — John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 202-203, 209, 212, 244; Xiaoping Yang, Robert North and Carl Romney, “CMR Nuclear Explosion Database (Revision 3): CMR Technical Report CMR-00/16,” August 2000, www.rdss.info; US Army Space and Missile Defense Command Monitoring Research Program “Nuclear Explosion Database,” www.rdss.info.

9 May 1966 China conducts its third nuclear test. This is an atmospheric test of a boosted fission device (U-235 and Lithium-6) that is air-dropped by an H-6 bomber and has an explosive yield of between 200 kilotons and 300 kilotons of TNT. — John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 201, 244; Xiaoping Yang, Robert North and Carl Romney, “CMR Nuclear Explosion Database (Revision 3): CMR Technical Report CMR-00/16,” August 2000, www.rdss.info; US Army Space and Missile Defense Command Monitoring Research Program “Nuclear Explosion Database,” www.rdss.info.

14 May 1965 China conducts its second nuclear test. This test is an atmospheric test of a fission (U-235) device, air-dropped by an H-6 bomber, and has an explosive yield of between 20 kilotons and 40 kilotons of TNT. — John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), p.244; Xiaoping Yang, Robert North and Carl Romney, “CMR Nuclear Explosion Database (Revision 3): CMR Technical Report CMR-00/16,” August 2000, www.rdss.info; US Army Space and Missile Defense Command Monitoring Research Program “Nuclear Explosion Database,” www.rdss.info.

Source: China Nuclear Chronology (https://media.nti.org/pdfs/china_nuclear_3.pdf)

Transmission-5. River Elegy 河殇 1988. Oceanic Blue Yellow River Silt.

River Elegy (Chinese: 河殇; pinyin: Héshāng) was a six-part documentary shown on China Central Television in 1988 which portrayed the decline of traditional Chinese culture. The film asserted that the Ming Dynasty’s ban on maritime activities alluded to the building of the Great Wall by China’s first emperor Ying Zheng. China’s land-based civilization was defeated by maritime civilizations backed by modern sciences, and was further challenged with the problem of life and death ever since the latter half of the 19th century, landmarked by the Opium War. Using the analogy of the Yellow River, China was portrayed as once at the forefront of civilization, but subsequently dried up due to isolation and conservatism. Rather, the revival of China must come from the flowing blue seas which represent the explorative, open cultures of the West and Japan. River Elegy caused immense controversy in mainland China due to its negative portrayal of Chinese culture. Rob Gifford, a National Public Radio journalist, said that the film used images and interviews to state that the concept of “the Chinese being a wonderful ancient people with a wonderful ancient culture was a big sham, and that the entire population needed to change.” Gifford said that the film’s most significant point was its attack on the Yellow River, a river which was a significant element of China’s historical development and which symbolizes ancient Chinese culture.

Using the ancient Chinese saying that “a dipperful of Yellow River water is seven-tenths mud,” the authors of the film use the river’s silt and sediment as a metaphor for Confucian traditions and the significance of the traditions which the authors believe caused China to stagnate. The authors hoped that Chinese traditional culture would end and be replaced by Western culture. The film symbolizes Chinese thinking with the “yellowness” of the Yellow River and Western thinking with the “blueness” of the ocean. The film also criticized the Great Wall, saying that it “can only represent an isolationist, conservative, and incompetent defense,” the imperial dragon on the Great Wall, calling it “cruel and violent,” and other Chinese symbols. The ending of River Elegy symbolized the authors’ dreams with the idea of the waters of the Yellow River emptying out of the river and mixing with the ocean. Gifford said that River Elegy reveals the thoughts of young intellectuals post-Mao Zedong and pre-Tiananmen Square and the freedoms that appeared around 1988. Gifford said that while the film did not openly criticize the Communist Party of China; instead it contained “not-so-subtle” attacks on Chinese imperial traditions that therefore would also criticize the contemporary political system. Conservatives in Mainland China attacked the film. After the events of Tiananmen Square some of the staff members of River Elegy were arrested and others fled Mainland China. Two of the main writers who escaped to the United States became evangelical Christians. This is a condensed version that contains the six episodes.

Maritime Silk Roads

21世纪海上丝绸之路

blue - oceanic - deep - limbic - unconscious

21st Century Space Race

中华人民共和国航天red - fast - conscious - escape velocity

中华人民共和国航天

Continental Silk Road Economic Belt

丝绸之路经济带

grey - everyday - dreamsend - treadmill

27.02.2020. Have been trying to develop this week a project called Chromabellum 1988 2049, I put together a really rough first video iteration – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VXMPBbJDrA- but trying to parse out and draw on the work of Derek Jarman into a chromatic lineage of Cold War relations between the west (blue) and east (red) that latently still machine the present am working on another video for now drafted as The Three Dimensions of the New Silk Soul… and working with the below triptych… a blue oceanic limbic liner moving slowly through a blue storm (there is in a sense something deeply meditative, unconscious, slow in the colour blue) … a red long march 5 rocket launching… escape velocity (in red, there’s something fast, conscious)… and a grey rail freight train moving across an empty landscape (a grey as a sort of everyday, a weight between the two dimensions), in a way I’m trying to open up a psychological model, the way Freud had his depth model, or Deleuze/Guattari their three ecologies, that the psyche is a movement vector of colouration which I think ties in with the story we are developing. They are also the three spaces of the Silk Roads, the maritime ocean roads… cosmic satellite space … the continental land belts. Below is from Derek Jarman’s Chroma, published in 1994 shortly after his death: https://blip.land/chromabellum-the-three-dimensions-of-the-new-silk-soul/

Ice has a memory. It remembers in detail and it remembers for a million years or more. Ice remembers forest fires and rising seas. Ice remembers the chemical composition of the air around the start of the last Ice Age, 110,000 years ago. It remembers how many days of sunshine fell upon it in a summer 50,000 years ago. It remembers the temperature in the clouds at a moment of snowfall early in the Holocene. It remembers the explosions of Tambora in 1815, Laki in 1783, Mount St Helens in 1482 and Kumae in 1454. It remembers the smelting boom of the Romans, and it remembers the lethal quantities of lead that were present in petrol in the decades after the Second World War. It remembers and it tells – tells us that we live on a fickle planet, capable of swift shifts and rapid reversals. Ice has a memory and the colour of this memory is blue. Ice has a memory and the colour of this memory is blue. High on the ice cap, snow falls and settles in soft layers known as firn. As the firn forms, air is trapped between snowflakes, and so too are dust and other particles. More snow falls, settling upon the existing layers of firn, starting to seal the air within them. More snow falls, and still more. The weight of snow begins to build up above the original layer, compressing it, changing the structure of the snow. The intricate geometries of the flakes begin to collapse. Under pressure, snow starts to sinter into ice. As ice crystals form, the trapped air gets squeezed together into tiny bubbles. This burial is a form of preservation. Each of those air bubbles is a museum, a silver reliquary in which is kept a record of the atmosphere at the time the snow first fell. Initially, the bubbles form as spheres. As the ice moves deeper down, and the pressure builds on it, those bubbles are squeezed into long rods or flattened discs or cursive loops.

The colour of deep ice is blue, a blue unlike any other in the world – the blue of time. The blue of time is glimpsed in the depths of crevasses. The blue of time is glimpsed at the calving faces of glaciers, where bergs of 100,000-year-old ice surge to the surface of fjords from far below the water level. The blue of time is so beautiful that it pulls body and mind towards it. Ice is a recording medium and a storage medium. It collects and keeps data for millennia. Unlike our hard disks and terrabyte blocks, which are quickly updated or become outdated, ice has been consistent in its technology over millions of years. Once you know how to read its archive, it is legible almost as far back – as far down – as the ice goes. Trapped air bubbles preserve details of atmospheric composition. The isotopic content of water molecules in the snow records temperature. Impurities in the snow – sulphuric acid, hydrogen peroxide – indicate past volcanic eruptions, pollution levels, biomass burning, or the extent of sea ice and its proximity. Hydrogen peroxide levels show how much sunlight fell upon the snow. To imagine ice as a ‘medium’ in this sense might also be to imagine it as a ‘medium’ in the supernatural sense: a presence permitting communication with the dead and the buried, across gulfs of deep time, through which one might hear distant messages from the Pleistocene. Ice has an exceptional memory – but it also suffers from memory loss. The weight on 2,000-year-old ice can reach half-a-ton per square inch. The air in this ice has been so compressed that cores brought up by deep drilling will fracture and snap as the air expands. This is why glaciers sound like shooting ranges. This is why if you were to drop a piece of very old blue ice in a glass of water or whisky, it might shatter the glass. Deeper still – in ice aged between 8,000 and 12,000 years – the pressure becomes so great that air bubbles can no longer survive as vacancies within the structure of the ice. They vanish as visible forms, instead combining with the ice to form an ice-air mixture called clathrate. Clathrate is harder to read as a medium, and the messages it holds are fainter, more encrypted. In mile-deep ice, individual layers can only just be made out as ‘greyish ghostly bands . . . visible in the focused beam of a fibre-optic lamp’. And because ice flows – because it continues to flow even when under immense pressures – it distorts its record, its layers folding and sliding, such that sequence can be almost impossible to discern.” At the deepest points of the Greenland and Antarctic ice cap, where the ice is miles deep and hundreds of thousands of years old, the weight is so great that it depresses the rock beneath it into the Earth’s crust. At that depth, the compressed ice acts like a blanket, trapping the geothermal heat emanating from the bedrock. That deepest ice absorbs some of that heat, and melts slowly into water. This is why there are freshwater lakes sunk miles below the Antarctic ice cap – 500 or more of these subglacial reservoirs, showing up as spectral dashed outlines on maps of the region, unexposed for millions of years, as alien as the ice-covered oceans thought to exist on Saturn’s moon, Enceladus. As a human mind might, late in life, struggle to remember its earliest moments – buried as they are beneath an accumulation of subsequent memories – so the oldest memory of ice is harder to retrieve, and more vulnerable to loss. (Robert Macfarlane, 2019)

‘One feature, the most distinctive of all, pits contemporary civilisation against those that have preceded it: speed. The metamorphosis occurred in the space of a single generation’, Marc Bloch, 1930s. This situation involves a second feature in turn: the accident. The gradual spread of catastrophic events not only affects the reality of the moment but causes anxiety and anguish for generations come. From incidents to accidents, from catastrophes to cataclysms, everyday life has become a kaleidoscope where we endlessly bang into or run up against what crops up, ex abrupto, out of the blue, so to speak. … Consciousness only survives now as an awareness of accidents

Transmission-6b. The Kalevalan Arc (Kulusuk, Novaya Zemlya, Marshall Islands)

The Protagonist moves through a solarine arc, chasing the cartridge, and the secret of the New Silk Soul

The Blue of Time (Kulusuk, Greenland) | Late summer off the coast of Kulusuk Island, south-east Greenland, and a single iceberg sweats in the channel. The berg is vast, perhaps 100 feet from sea to summit, shaped like a mainsail with a rounded tip. It glistens white as wet wax. Its submerged bulk shows as a bottle-green aura. Dark blue of the channel, sharp blue of the cloudless sky. Daytime moon above a shield-shaped mountain. On the far side of the channel, a glacier runs down to the water, six miles or so distant, the cliff of the calving face faintly visible. All through that hot summer of 2016, before I went to Greenland, ice around the world was yielding up long-held secrets. The cryosphere was melting, and as it melted things that would have better stayed buried were coming to the surface. On the Yamal peninsula, between the Kara Sea and the Gulf of Ob, 4,500 square miles of permafrost thawed. Cemeteries and animal burial grounds turned to slush. Reindeer corpses that had died of anthrax seventy years earlier were exposed to the air. Twenty-three people were infected, their skin blackened with lesions. One, a child, died. Russian veterinarians travelled the region dressed in white anti-contamination suits, vaccinating reindeer and their herders. Russian troops burned infected corpses in high-temperature pyres. Russian agriculturalists said that nothing would ever grow in the region again. Russian epidemiologists predicted other releases from Arctic burial sites and shallow graves: smallpox from victims who had perished in the late 1800s, giant viruses that had been long-dormant in the frozen bodies of mammoths. On the Siachen glacier in the Karakoram, where Indian and Pakistani troops have been fighting a forgotten war since 1984, the retreating ice was revealing spent shells, ice axes, bullets, abandoned uniforms, vehicle tyres, radio sets – and slaughtered human bodies.

In north-west Greenland, a buried Cold War US military base and the toxic waste it contained began to rise. Camp Century was excavated by the US army engineering corps in 1959. They tunnelled into the ice cap and created a hidden town: a two-mile network of passageways housing laboratories, a shop, a hospital, a cinema, a chapel, and accommodation for 200 soldiers, all powered by the world’s first mobile nuclear generator. The base was abandoned in 1967. The departing soldiers took the reaction chamber of the nuclear generator with them. But they left the rest of the base’s infrastructure intact under the ice, including the biological, chemical and radioactive waste it contained, assuming – as the Pentagon closure reports declared – that it would be ‘preserved for eternity’ by the perpetual snowfalls of northern Greenland. It is all interred there still: some 200,000 litres of diesel fuel and unknown amounts of radioactive coolant and other pollutants, including PCBs. But as global temperatures have risen, so snowmelt is forecast to exceed snow accumulation in the region of Camp Century. In a dynamic I have seen so often in the underland that it has become a master trope, troublesome history thought long since entombed is emerging again. Uneasy stories circulated about disappearances in the ice. A Russian businessman had flown in on the east coast, wearing a camel-skin coat and carrying a briefcase, and never flown out again. A Japanese hiker had vanished in the west of the country, been missing for weeks. Local people spoke half-jokingly of the kisuwak, the wild creature that roamed the ice and snatched unwary travellers – an animate version of the glacial crevasse or the silky-thin sea ice. In that region, at this time of history, it felt as if there were many places where one might fall right through the world’s surface.“Kulusuk is one of a handful of small settlements on the east coast of Greenland – fingernail-holds on the edges of this great island. Fewer than 3,000 people live on around 1,600 miles of coastline. Like many of the smaller Greenlandic settlements, Kulusuk is a society ruptured by transition – a previously part-nomadic subsistence-hunting culture, into which modernity has intruded in the forms of stasis and alcohol. Ice has a social life. Its changeability shapes the culture, language and stories of those who live near it. In Kulusuk, the consequences of recent changes are widely apparent. The inhabitants of this village are part of the precariat of a volatile, fast-warping planet. The melting of the ice, together with forced settlement and other factors, has had severe effects upon the mental and physical health of native Greenlanders, causing rates of depression, alcoholism, obesity and suicide to rise, especially in small communities. ‘The loss of that landscape of ice,’ writes Andrew Solomon, studying depression rates in Greenland, ‘is not merely an environmental catastrophe, but also a cultural one.’ The Inuktitut of Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic have begun to use a word that refers at once to the changes in the weather, the changes in the ice, and the consequent changes in the people themselves. The word is uggianaqtuq – meaning ‘to behave strangely, unpredictably’. The last few years have seen the granting of more than fifty mining licences in Greenland, allowing exploratory mining for gold, rubies, diamonds, nickel and copper, among other minerals. And on the southern tip of Greenland, close to a small town with high unemployment called Narsaq, lies one of the world’s largest uranium deposits. Niels Bohr, the Nobel Prize-winning atomic physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, visited Narsaq in 1957, shortly after the discovery of the deposit. A joint Chinese-Australian mining project now proposes to establish an open-pit mine behind Narsaq, in order to acquire not only uranium but also the rare earth minerals used in wind turbines, mobile phones, hybrid cars and lasers. That evening in Kulusuk a lurid sunset brews above the village, lilac and orange backlighting a sawtooth ridge of peaks, with incandescent reefs of ribbed clouds. It is alpenglow of a kind – but of an incredible wattage. ‘It’s the ice cap that makes sunsets like this,’ Matt explains. ‘It’s probably the biggest mirror in the world: hundreds of thousands of square miles of ice reflecting up the sun as it dips towards the horizon.” The day before I go to Olkiluoto Island and down to the hiding place, I wait in the little nearby town of Rauma, reading the great folk epic of Finland, the Kalevala.

The Kalevala is a long poem of many voices and many stories which – like the Iliad and the Odyssey – grows out of diverse and deep-rooted traditions, from Baltic song to Russian storytelling. It existed chiefly as a mutable oral text for more than a thousand years, until in the nineteenth century the Kalevala was collected, edited and published by the Finnish scholar Elias Lönnrot, giving us the mostly fixed version we now have. Lönnrot’s Kalevala is made up of many intertwining narratives that combine the mythical and the lyrical with the mundane and the logistical, and that together dramatize a northern people’s engagement with a hard, beautiful landscape of forests, islands and lakes. In its layering of different ages of origin, the Finnish scholar Matti Kuusi compares the poem’s own history of making with ‘the numerous strata of a burial mound in which many generations . . . and their artefacts have been buried’. The Kalevala is a haunting epic that has preoccupied me for some years, obsessed as it is with the power of word, incantation and story to change the world into which they are uttered. Its heroes are language masters and wonder-workers – and the greatest of them is called Väinämöinen, whose name translates memorably as ‘Hero of the Slow-Moving River’. Partway through the poem, Väinämöinen is given the task of descending to the underland. Hidden in the Finnish forests, he is told, is the entrance to a tunnel that leads to a cavern far underground. In that cavern are stored materials of huge energy: spells and enchantments which, when spoken, will release great power. To approach this subterranean space safely Väinämöinen must protect himself with shoes of copper and a shirt of iron, lest he be damaged by what it contains. The Kalevala is fascinated by the underland; by the safe storage of dangerous materials and the safe retrieval of precious materials. At the poem’s heart is a magical object or substance known as ‘Sampo’ or the ‘Sammas’; constructed by the blacksmith Ilmarinen, another of the Kalevala’s supernatural heroes, and stored inside the ‘copper slope’ of a ‘rocky hill’, protected by a gate with ten locks. This enchanted artefact, most often figured as a mill or quern, brings power, wealth and fortune to whoever controls it. It is – in modern terms – a weapons system, a rich raw resource, a nation’s organized industry, or a nuclear power station. The Sampo grinds out flour, it grinds out money – and it grinds out time. One of its given tasks is to grind out the age of the world, causing epochs to yield to one another in an immense cycle of precessions. The world has changed too much . . . we are in the Anthropocene. (Underland, Robert Macfarlane, 2019)

Project 4.1 The Secrets of the Marshall Islands 马绍尔群岛的秘密 description: Human rights the American Way 美国式的人权 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LXvoRv-v9fg) as fore of nuclear legacies in Radical Decoupling (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3mk0gpyRIQ)

The Hiding Place (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4JURzI5dTU) | The Seed Vault (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXBnkRE9gM4)

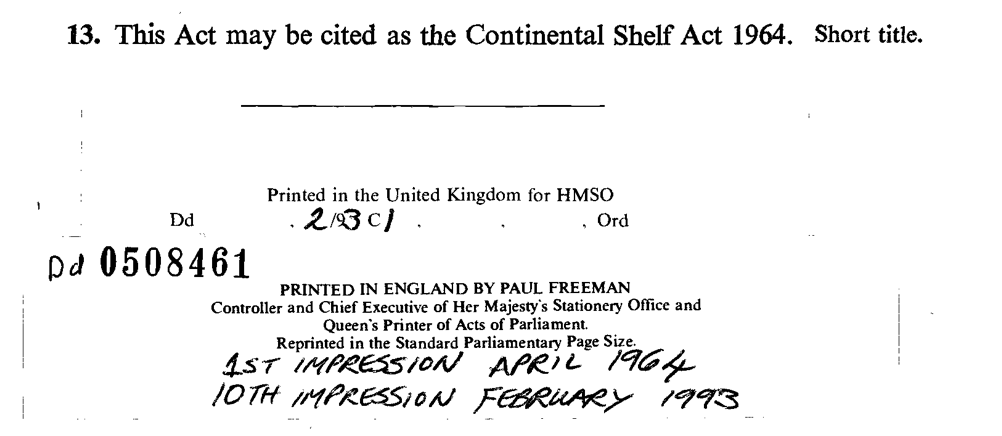

Transmission 6c. Retinal Lake 视网膜 湖 Rainlight Northsea Ekofisk

Rainlight northsea, dad was born in Bristol, Dziadek left the northsea, norway operations behind, in shifting red light, when came its oil boom. Awhile, gulfstreamed in rebel county, Bantry Bay, the Suez closure boomed the Whiddy Depot, then came the explosion, the Betelgeuse that blew the windows out in town the oil rig, 01:00am Monday 8 January 1979, a rumbling or cracking noise followed by a huge explosion within the hull – siniys and goluboys – radiating outward, heat and light and dissipation-gauze, then came Last Breath, 2012, the man lost beneath the North Sea in fading light, severed from the umbilical in rough drift, and history all came bound up in the rainlight shearing off the North Sea, vapours fractionating into distant singular paths and homes and heats, marriages, divorces, deaths, births – then the two Delillo quotes I read last night came flooding back (01.05.20):

He remained at the sink. He ran the water over the skillet, then scoured some more, then ran the water, then scoured, then ran the water. He heard her come up the steps and open the door. She walked into the hallway and ran he ran the water, keeping his back to the room. She said, “I took the taxi from the bus station instead of calling. I had just enough money left for the taxi and the tip and I wanted to arrive totally broke.” The wind blows the door and look what walks in.” “Actually I have two dollars”. He didn’t turn around. He would have to adjust to this. He’d naturally fitted himself to the role, for some years now, of friend abandoned or lover discarded. We all know how the thing we secretly fear is not a secret at all but the open and eternal thing that predicts its own recurrence. He turned off the water and put the skillet in the drain basket and waited. (Don Delillo, Mao II, page 219) A silver flare sails briefly over the streets, bits of incandescence trailing away. Radio voices calling all around her. Beirut, Beirut. They crowd in toward her, pressing with a mournful force. People calling from basement shelters, faces in shadow, clothing going dark with heavy sweat, sleeping children curled around their war toys. […] all the refugees, pray for their dead and wait for the shelling to subside. The war is so fucking simple. It is the lunar part of us that dreams of wasted terrain. She hears their voices calling across the levelled city. (Don Delillo, Mao II, page 239)

The unconscious stream of history – solar winds, telluric depth, and chance – quantum in a way that all possible states are carried on the wind, as long as no one is watching anything goes – Delillo said Libra, on Oswald, was a sense-making of history centred on the role of the irrational and its instrument, the man who, as Delillo told Ann Arensberg, ‘stepped outside history and let the forces of destiny move him where they would – non-historical forces like dreams, coincidences, intuitions, the alignment of the heavenly bodies, all these things. the workings of dreams, coincidence, astrology – all that lies outside systems of historical logic. Only the ‘language of the night sky’ can express the truth behind Oswald’s act, but it is an astrological ‘truth at the edge of human affairs’.

The thin porous material was used to construct real fields on a soap bubble world, they called it the Von Uexkull System, installed by the UN-SCO dyad across the Sinoparallel and Atlantic States, the World-Island was a densely populated soap universe, it was all part of the great reversion from the Non-Geometrists of the late 20th and Early 21st Century and the great wave of Immunology Sciences that emerged in the schism of COVID-19…. blowing the straw from both ends, the great power popping and expanding worlds…

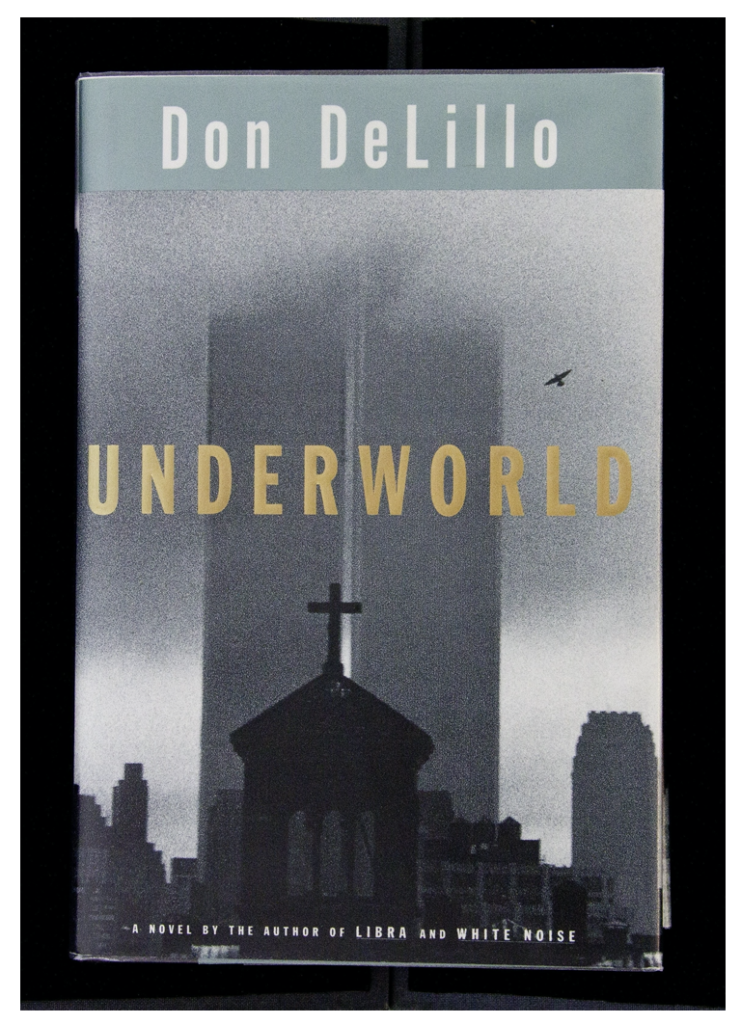

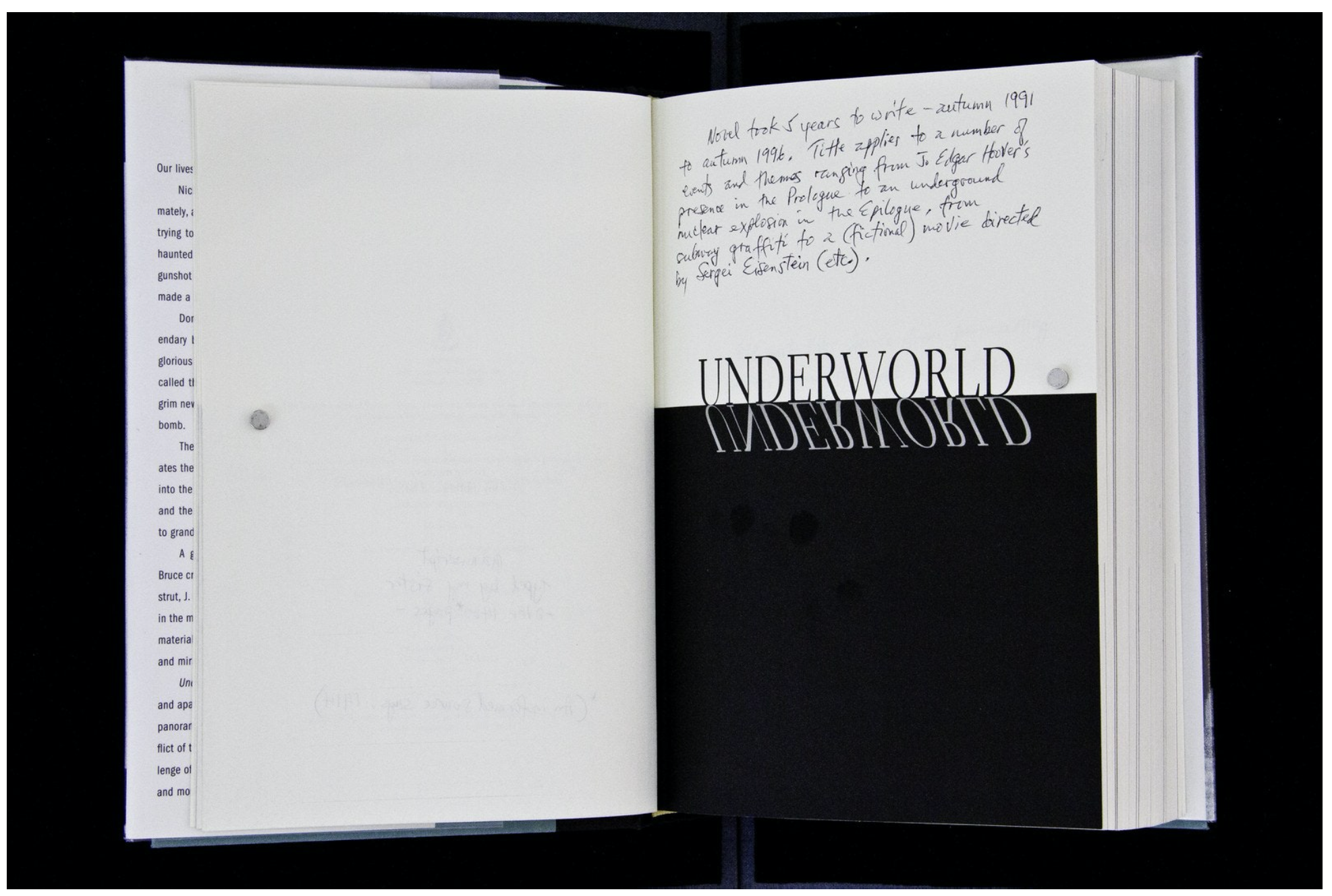

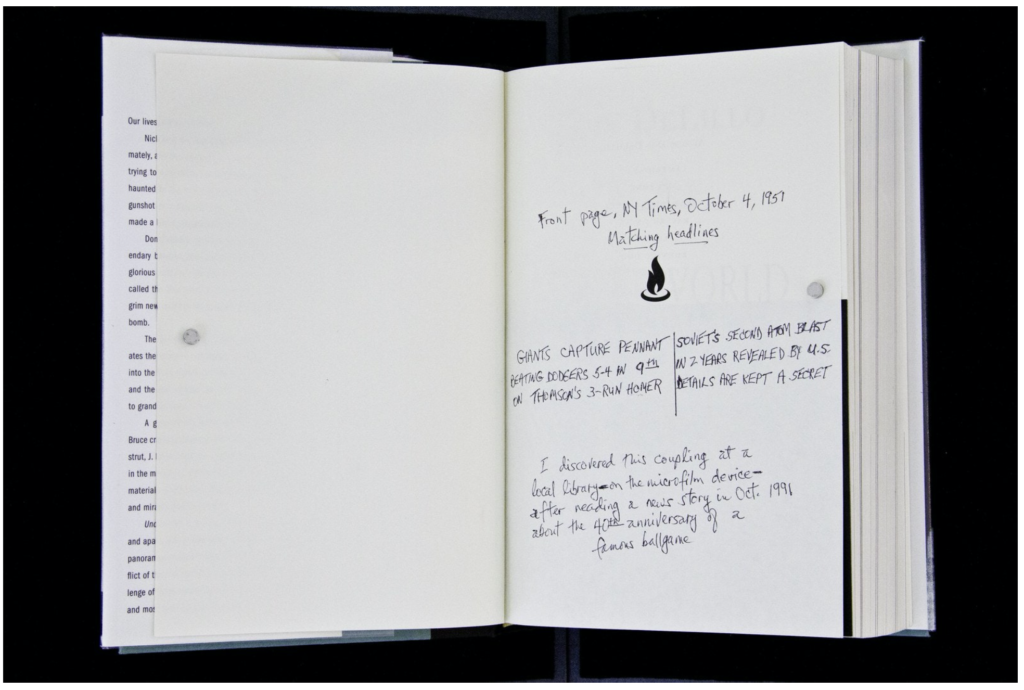

UNDERLAND, racing under the North Sea for dark matter

Transmission 7. Gasbuggy, New Mexico | Operation Plowshare | Dec 10 1967

THE ATOM UNDERGROUND profiles Project Gasbuggy and Project Plowshare, which were ill-fated attempts to demonstrate the use of nuclear detonations for peaceful purposes, in this case extracting more oil and natural gas from underground through nuclear fracking. Plowshare was the overall United States term for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. It was the US portion of what are called Peaceful Nuclear Explosions (PNE). Successful demonstrations of non-combat uses for nuclear explosives include rock blasting, stimulation of tight gas, chemical element manufacture (test shot Anacostia resulted in Curium-250m being discovered), unlocking some of the mysteries of the so-called “r-Process” of stellar nucleosynthesis and probing the composition of the Earth’s deep crust, creating reflection seismology Vibroseis data which has helped geologists and follow on mining company prospecting. Negative impacts from Project Plowshare’s 27 nuclear projects generated significant public opposition, which eventually led to the program’s termination in 1977. These consequences included Tritiated water (projected to increase by CER Geonuclear Corporation to a level of 2% of the then-maximum level for drinking water) and the deposition of fallout from radioactive material being injected into the atmosphere before underground testing was mandated by treaty. Project Gasbuggy was an underground nuclear detonation carried out by the United States Atomic Energy Commission on December 10, 1967 in rural northern New Mexico. It was part of Operation Plowshare, a program designed to find peaceful uses for nuclear explosions. Gasbuggy was carried out by the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory and the El Paso Natural Gas Company, with funding from the Atomic Energy Commission. Its purpose was to determine if nuclear explosions could be useful in fracturing rock formations for natural gas extraction. The site, lying in the Carson National Forest, is approximately 34 km (21 mi) southwest of Dulce, New Mexico and 87 km (54 mi) east of Farmington, and was chosen because natural gas deposits were known to be held in sandstone beneath Leandro Canyon.[3] A 29 kt (120 TJ) device was placed at a depth of 1,288 m (4,227 ft) underground, then the well was backfilled before the device was detonated; a crowd had gathered to watch the detonation from atop a nearby butte. The detonation took place after a couple of delays, the last one caused by a breakdown of the explosive refrigeration system. The detonation produced a rubble chimney that was 24 m (80 ft) wide and 102 m (335 ft) high above the blast center. After an initial surface cleanup effort the site sat idle for over a decade. A later surface cleanup effort primarily tackled leftover toxic materials. In 1978, a marker monument was installed at the Surface Ground Zero (SGZ) point that provided basic explanation of the historic test. Below the main plaque lies another which indicates that no drilling or digging is allowed without government permission. The site is publicly accessible via the Carson National Forest, F.S. 357 dirt road/Indian J10 that leads into the Carson National Forest. Following the Project Gasbuggy test, two subsequent nuclear explosion fracturing experiments were conducted in western Colorado in an effort to refine the technique. They were Project Rulison in 1969 and Project Rio Blanco in 1973. In both cases the gas radioactivity was still seen as too high and in the last case the triple-blast rubble chimney structures disappointed the design engineers. Soon after that test the ~ 15-year Project Plowshare program funding dried up. These early fracturing tests were later superseded by hydraulic fracturing (fracking) technologies.

Transmission 8. 1969 Department of Defense Pacific Command Vietnam War 25004

Beyond the West Coast of the United States are 85 million square miles of ocean, stretching from the Aleutian Islands in the north to the South Pole; past the Hawaiian Islands and onto Guam and the Philippines and continuing to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean and beyond. In total, about 40 percent of the globe are covered by those waters — and are the responsibility of the United States Pacific Command. That dramatic narrative introduces the viewer to this color film and the unified combatant command of the US armed forces responsible for the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. (It is also the oldest and largest of the unified combatant commands.) Produced by the Department of Defense circa 1969, the film shows a montage of aircraft, soldiers, and sailors, as the narrator quotes President Dwight D. Eisenhower as saying that separate air, land, and sea warfare are no longer viable, and that all services must operate as a single unit under the command of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC). At mark 03:08, an officer (played by veteran actor William Boyett) explains the purpose and mission of Pacific Command, as well as its chain of command. Following a reminder of the lives lost in World War II’s Pacific Theater at mark 05:10, the narrator explains that areas in the Pacific continue to be at risk, as a map of Southeast Asia is shown on the screen. Following a review of military commands in the Pacific, the film continues to explore the importance of Pacific Command, from the strategic position of B-52 bombers on Guam to the deployment of nuclear submarines beneath the water. Although the sea has been kept free, the narrator continues at mark 08:38, that is not the case for all lands, as the film shows scenes of US military personnel — “welcome guests” — mingling with residents, teaching them skills, or providing medical services. The viewer is also taken to various bases, including Clark Air Force Base and the US Naval Base at Subic Bay in the Philippines, with those stationed there poised to act if and when needed. At mark 10:50, the film takes its viewers to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North Korea and South Korea, as we learn how the armistice line is permanently lined by troops from the US 8th Army and the Republic of Korea — “a capable deterrent against overt Communist aggression.” Troops stationed in Korea are also shown socializing with residents and teaching boys and girls volleyball, as well as assisting with farming and creating roads and bridges. As the film takes us to the coast of Japan at mark 14:39, we see scenes at Tachikawa Airfield in Tokyo and army depots tasked with providing supplies to Pacific commands. At times, troops are also forced into combat, as the film shows several minutes of footage from the jungles of Vietnam beginning at mark 17:17, and an explanation that the US Army and Marine Corps are trying to “persuade” North Vietnamese forces to withdraw from the south, with assistance from the Air Force and Navy. The Navy and Coast Guard also aid South Vietnamese forces with stopping the re-supply of North Vietnamese forces, we learn starting at mark 20:35. With continued assistance from South Vietnamese forces, the Pacific Command will continue its efforts in Southeast Asia and across all 85 million square miles it is charged to protect, the narrator reminds the viewer, as the film comes to an end.

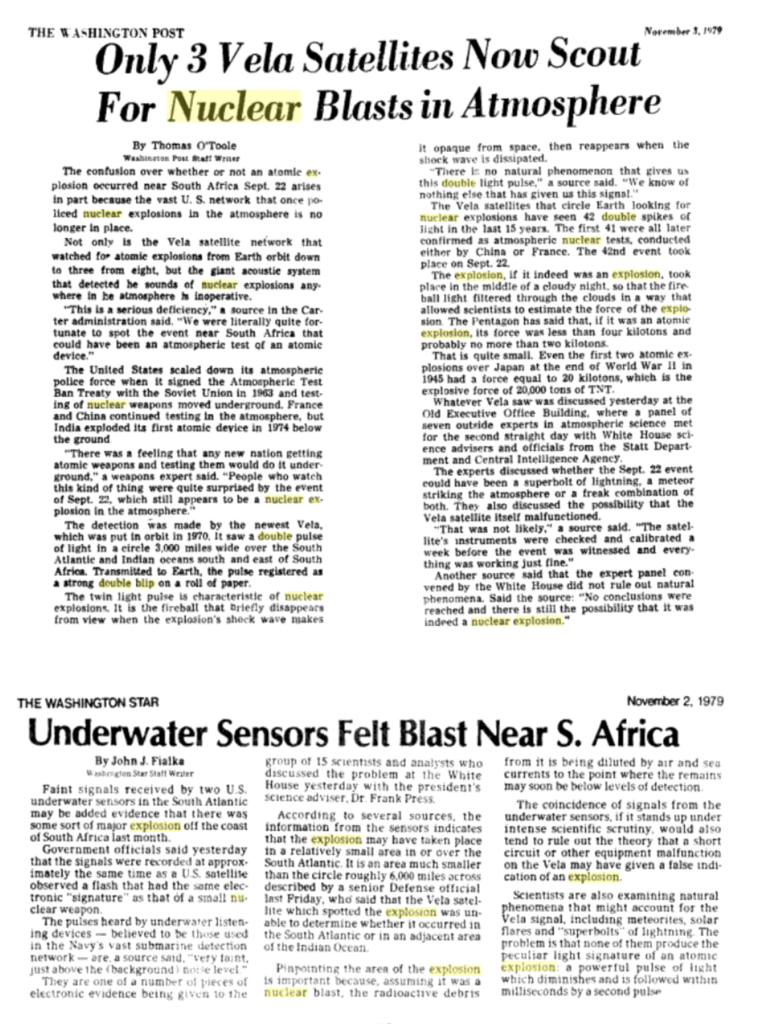

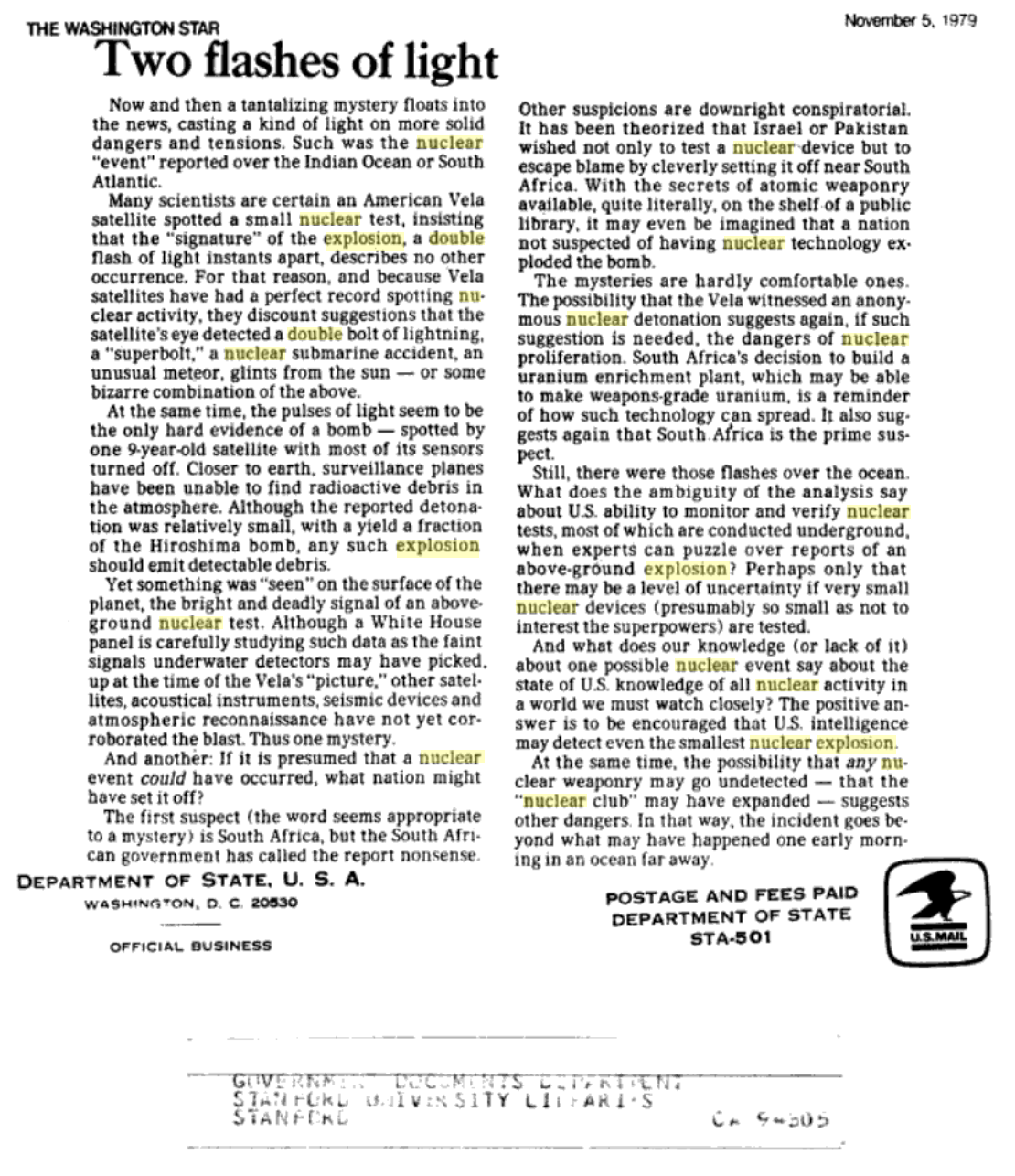

Transmission 9. The Vela Incident 22091971 00:53 UTC | Prince Edwards Island Indian Ocean

Made by the U.S. Air Force’s Eastern Test Range, this rarely seen film shows the launch of the special Vela satellite designed to detect radiation from nuclear tests. The film shows the Titan IIIC launch vehicle used in the program with a specific focus on the C-18 / Vela – VB mission. This was the last of the Vela satellites, launched on April 8, 1970. The Titan IIIC shown was the 100th launched at the Eastern Test Range. The Titan IIIC consisted of a two-stage Titan core and upper stage called the Titan Transtage, both burning hypergolic liquid fuel, and two large UA1205 solid rocket boosters. Vela was the name of a group of satellites developed as the Vela Hotel element of Project Vela by the United States to monitor compliance with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty by the Soviet Union. Vela started out as a small budget research program in 1959. It ended 26 years later as a successful, cost-effective military space system, which also provided scientific data on natural sources of space radiation. In the 1970s, the nuclear detection mission was taken over by the Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites. In the late 1980s, it was augmented by the Navstar Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites. The program is now called the Integrated Operational Nuclear Detection System (IONDS). The total number of satellites built was 12, six of the Vela Hotel design and six of the Advanced Vela design. The Vela Hotel series was to detect nuclear initiations in space, while the Advanced Vela series was to detect not only nuclear explosions in space but also in the atmosphere. All spacecraft were manufactured by TRW and launched in pairs, either on an Atlas-Agena or Titan III-C boosters. They were placed in orbits of 118,000 km (73,000 miles),[1] well above the Van Allen radiation belts. Their apogee was about one-third of the distance to the Moon. The first Vela Hotel pair was launched on October 17, 1963,[2] one week after the Partial Test Ban Treaty went into effect, and the last in 1965. They had a design life of six months, but were actually shut down after five years. Advanced Vela pairs were launched in 1967, 1969 and 1970. They had a nominal design life of 18 months, later changed to 7 years. However, the last satellite to be shut down was Vehicle 9 in 1984, which had been launched in 1969 and had lasted nearly 15 years. The Titan IIIC was an expendable launch system used by the United States Air Force from 1965 until 1982. It was the first Titan booster to feature large solid rocket motors and was planned to be used as a launcher for the Dyna-Soar and Manned Orbiting Laboratory, though both programs were cancelled before any astronauts flew. The majority of the launcher’s payloads were DoD satellites, namely for military communications and early warning, though one flight (ATS-6) was performed by NASA. The Titan IIIC was launched exclusively from Cape Canaveral while its sibling, the Titan IIID, was launched only from Vandenberg AFB.

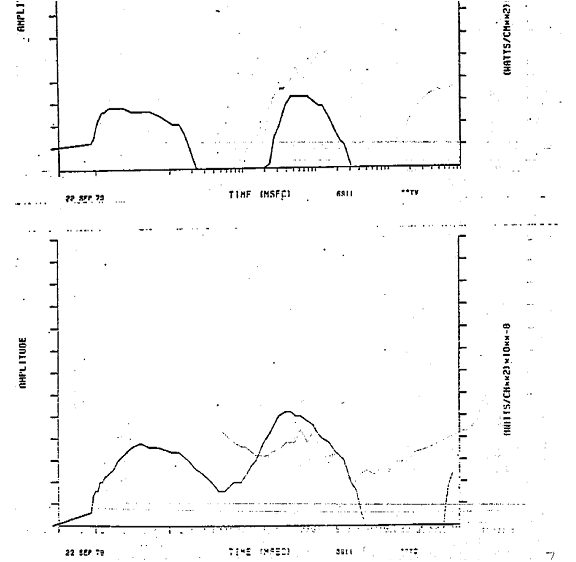

The Vela incident, also known as the South Atlantic Flash, was an unidentified double flash of light detected by an American Vela Hotel satellite on 22 September 1979 near the Prince Edward Islands in the Indian Ocean. The cause of the flash remains officially unknown, and some information about the event remains classified.[1] While it has been suggested that the signal could have been caused by a meteoroid hitting the satellite, the previous 41 double flashes detected by the Vela satellites were caused by nuclear weapons tests.[2][3][4] Today, most independent researchers believe that the 1979 flash was caused by a nuclear explosion[1][5][6][7] — perhaps an undeclared nuclear test carried out by South Africa and Israel.[8]The “double flash” was detected on 22 September 1979, at 00:53 UTC, by the American Vela satellite OPS 6911 (also known as Vela 10 and Vela 5B[9]), which carried various sensors designed to detect nuclear explosions that contravened the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. In addition to being able to detect gamma rays, X-rays, and neutrons, the satellite also contained two silicon solid-state bhangmeter sensors that could detect the dual light flashes associated with an atmospheric nuclear explosion: the initial brief, intense flash, followed by a second, longer flash.[4 The satellite reported a double flash, which could be characteristic of an atmospheric nuclear explosion of two to three kilotons, in the Indian Ocean between the Crozet Islands (a sparsely inhabited French possession) and the Prince Edward Islands (which belong to South Africa) at 47°S 40°E. Other systems data, such as Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) and Missile Impact Location System (MILS) that were established by the United States and NATO to detect Soviet submarines and the locations where used missile test warheads splashed down, respectively, were searched in an effort to gain more knowledge on the possibility of a nuclear detonation in the region. These data were found not to have enough substantial evidence of a detonation of a nuclear weapon.[11] United States Air Force surveillance aircraft flew 25 sorties over that area of the Indian Ocean from 22 September to 29 October 1979 to carry out atmospheric sampling.[12] Studies of wind patterns confirmed that fall-out from an explosion in the southern Indian Ocean could have been carried from there to southwestern Australia.[13] It was reported that low levels of iodine-131 (a short-half-life product of nuclear fission) were detected in sheep in the southeastern Australian States of Victoria and Tasmania soon after the event. Sheep in New Zealand showed no such trace.[13][14] The Arecibo ionospheric observatory and radio telescope in Puerto Rico detected an anomalous ionospheric wave during the morning of 22 September 1979, which moved from the southeast to the northwest, an event that had not been observed previously.[15]

The explosion was picked up by a pair of sensors on only one of the several Vela satellites; other similar satellites were looking at different parts of the Earth, or weather conditions precluded them seeing the same event.[22] The Vela satellites had previously detected 41 atmospheric tests—by countries such as France and the People’s Republic of China—each of which was subsequently confirmed by other means, including testing for radioactive fallout. The absence of any such corroboration of a nuclear origin for the Vela incident also suggested that the “double flash” signal was a spurious “zoo” signal of unknown origin, possibly caused by the impact of a micrometeoroid. Such “zoo” signals which mimicked nuclear explosions had been received several times earlier.[23] Their report noted that the flash data contained “many of the features of signals from previously observed nuclear explosions”,[24] but that “careful examination reveals a significant deviation in the light signature of the 22 September event that throws doubt on the interpretation as a nuclear event”. The best analysis that they could offer of the data suggested that, if the sensors were properly calibrated, any source of the “light flashes” were spurious “zoo events”. Thus their final determination was that while they could not rule out that this signal was of nuclear origin, “based on our experience in related scientific assessments, it is our collective judgment that the September 22 signal was probably not from a nuclear explosion”.[25] Victor Gilinsky (former member of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission) argued that the science panel’s findings were politically motivated.[15] Some data seemed to confirm that a nuclear explosion was the source for the “double flash” signal. An “anomalous” traveling ionospheric disturbance was measured at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico at the same time,[15] but many thousands of miles away in a different hemisphere of the Earth. A test in Western Australia conducted a few months later found some increased nuclear radiation levels.[26][page needed] A detailed study done by New Zealand’s National Radiation Laboratory found no evidence of excess radioactivity, and neither did a U.S. Government-funded nuclear laboratory.[27] Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists who worked on the Vela Hotel program have professed their conviction that the Vela Hotel satellite’s detectors worked properly.[15][28] Leonard Weiss, at the time Staff Director of the Senate Subcommittee on Energy and Nuclear Proliferation, has also raised concerns about the findings of the Ad-Hoc Panel, arguing that it was set up by the Carter administration to counter embarrassing and growing opinion that it was an Israeli nuclear test.[29] Specific intelligence about the Israeli nuclear program was not shared with the panel whose report therefore produced the plausible deniability that the administration sought.[29]