low earth

He worked in satellites, spotting demagnetisation facilities, hunting submarines from the air https://uk.comsol.com/blogs/reducing-magnetic-signature-submarine/ https://physicsworld.com/a/hunting-submarines-from-the-air/ / https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/submarine-detection-and-monitoring-open-source-tools-and-technologies/

Tracing the Polaris arc. Naval college, spent learning synthetic aperture radar, hydro-acoustic monitoring, a dissertation on EMP Strike on Kansas City. When Starfish Prime lit up the Pacific, a New Zealand patrol found the ocean transparent, “The electromagnetically charged aurora glow from the Starfish Prime shot lasted for hours. An interesting side effect was that the Royal New Zealand Air Force was aided in anti-submarine maneuvers by the light from the explosion. Land, airborne, and sea sensors reported strong electromagnetic signals at many hundreds of kilometers from the blast. Microbarograph signals from the detonation were observed at Johnston and Christmas Islands. Magnetic field disturbances were felt throughout the world to include both the North and South poles, according to the technical findings (Loadabrand and Dolphin 1962, 31).”

Human Moments in World War III, from The Angel Esmerelda (Don Delillo, 1983)

A note about Vollmer. He no longer describes the earth as a library globe or a map that has come alive, as a cosmic eye staring into deep space. This last was his most ambitious fling at imagery. The war has changed the way he sees the earth. The earth is land and water, the dwelling place of mortal men, in elevated dictionary terms. He doesn’t see it anymore (storm-spiraled, sea-bright, breathing heat and haze and color) as an occasion for picturesque language, for easeful play or speculation. At two hundred and twenty kilometers we see ship wakes and the larger airports. Icebergs, lightning bolts, sand dunes. I point out lava flows and cold-core eddies. That silver ribbon off the Irish coast, I tell him, is an oil slick. This is my third orbital mission, Vollmer’s first. He is an engineering genius, a communications and weapons genius, and maybe other kinds of genius as well. As mission specialist I’m content to be in charge. (The word specialist, in the standard usage of Colorado Command, refers here to someone who does not specialize.) Our spacecraft is designed primarily to gather intelligence. The refinement of the quantum-burn technique enables us to make frequent adjustments of orbit without firing rockets every time. We swing out into high wide trajectories, the whole earth as our psychic light, to inspect unmanned and possibly hostile satellites. We orbit tightly, snugly, take intimate looks at surface activities in untraveled places. The banning of nuclear weapons has made the world safe for war. I try not to think big thoughts or submit to rambling abstractions. But the urge sometimes comes over me. Earth orbit puts men into philosophical temper. How can we help it? We see the planet complete, we have a privileged vista. In our attempts to be equal to the experience, we tend to meditate importantly on subjects like the human condition. It makes a man feel universal, floating over the continents, seeing the rim of the world, a line as clear as a compass arc, knowing it is just a turning of the bend to Atlantic twilight, to sediment plumes and kelp beds, an island chain glowing in the dusky sea. I tell myself it is only scenery. I want to think of our life here as ordinary, as a housekeeping arrangement, an unlikely but workable setup caused by a housing shortage or spring floods in the valley.

Vollmer does the systems checklist and goes to his hammock to rest. He is twenty-three years old, a boy with a longish head and close-cropped hair. He talks about northern Minnesota as he removes the objects in his personal-preference kit, placing them on an adjacent Velcro surface for tender inspection. I have a 1901 silver dollar in my personal-preference kit. Little else of note. Vollmer has graduation pictures, bottle caps, small stones from his backyard. I don’t know whether he chose these items himself or whether they were pressed on him by parents who feared that his life in space would be lacking in human moments. Our hammocks are human moments, I suppose, although I don’t know whether Colorado Command planned it that way. We eat hot dogs and almond crunch bars and apply lip balm as part of the presleep checklist. We wear slippers at the firing panel. Vollmer’s football jersey is a human moment. Outsize, purple and white, of polyester mesh, bearing the number 79, a big man’s number, a prime of no particular distinction, it makes him look stoop-shouldered, abnormally long-framed.

“I still get depressed on Sundays,” he says. “Do we have Sundays here?” “No, but they have them there and I still feel them. I always know when it’s Sunday.”“Why do you get depressed?” “The slowness of Sundays. Something about the glare, the smell of warm grass, the church service, the relatives visiting in nice clothes. The whole day kind of lasts forever.” “I didn’t like Sundays either.” “They were slow but not lazy-slow. They were long and hot, or long and cold. In summer my grandmother made lemonade. There was a routine. The whole day was kind of set up beforehand and the routine almost never changed. Orbital routine is different. It’s satisfying. It gives our time a shape and substance. Those Sundays were shapeless despite the fact you knew what was coming, who was coming, what we’d all say. You knew the first words out of the mouth of each person before anyone spoke. I was the only kid in the group. People were happy to see me. I used to want to hide.” “What’s wrong with lemonade?” I ask.”

A battle-management satellite, unmanned, reports high-energy laser activity in orbital sector Dolores. We take out our laser kits and study them for half an hour. The beaming procedure is complex, and because the panel operates on joint control only, we must rehearse the sets of established measures with the utmost care. A note about the earth. The earth is the preserve of day and night. It contains a sane and balanced variation, a natural waking and sleeping, or so it seems to someone deprived of this tidal effect. This is why Vollmer’s remark about Sundays in Minnesota struck me as interesting. He still feels, or claims he feels, or thinks he feels, that inherently earthbound rhythm. To men at this remove, it is as though things exist in their particular physical form in order to reveal the hidden simplicity of some powerful mathematical truth. The earth reveals to us the simple awesome beauty of day and night. It is there to contain and incorporate these conceptual events. Vollmer in his shorts and suction clogs resembles a high school swimmer, all but hairless, an unfinished man not aware he is open to cruel scrutiny, not aware he is without devices, standing with arms folded in a place of echoing voices and chlorine fumes. There is something stupid in the sound of his voice. It is too direct, a deep voice from high in the mouth, slightly insistent, a little loud. Vollmer has never said a stupid thing in my presence. It is just his voice that is stupid, a grave and naked bass, a voice without inflection or breath. We are not cramped here. The flight deck and crew quarters are thoughtfully designed. Food is fair to good. There are books, videocassettes, news and music. We do the manual checklists, the oral checklists, the simulated firings with no sign of boredom or carelessness. If anything, we are getting better at our tasks all the time. The only danger is conversation.

I try to keep our conversations on an everyday plane. I make it a point to talk about small things, routine things. This makes sense to me. It seems a sound tactic, under the circumstances, to restrict our talk to familiar topics, minor matters. I want to build a structure of the commonplace. But Vollmer has a tendency to bring up enormous subjects. He wants to talk about war and the weapons of war. He wants to discuss global strategies, global aggressions. I tell him now that he has stopped describing the earth as a cosmic eye he wants to see it as a game board or computer model. He looks at me plain-faced and tries to get me into a theoretical argument: selective space-based attacks versus long, drawn-out, well-modulated land-sea-air engagements. He quotes experts, mentions sources. What am I supposed to say? He will suggest that people are disappointed in the war. The war is dragging into its third week. There is a sense in which it is worn out, played out. He gathers this from the news broadcasts we periodically receive. Something in the announcer’s voice hints at a letdown, a fatigue, a faint bitterness about—something. Vollmer is probably right about this. I’ve heard it myself in the tone of the broadcaster’s voice, in the voice of Colorado Command, despite the fact that our news is censored, that “despite the fact that our news is censored, that they are not telling us things they feel we shouldn’t know, in our special situation, our exposed and sensitive position. In his direct and stupid-sounding and uncannily perceptive way, young Vollmer says that people are not enjoying this war to the same extent that people have always enjoyed and nourished themselves on war, as a heightening, a periodic intensity. What I object to in Vollmer is that he often shares my deep-reaching and most reluctantly held convictions. Coming from that mild face, in that earnest resonant run-on voice, these ideas unnerve and worry me as they never do when they remain unspoken. I want words to be secretive, to cling to a darkness in the deepest interior. Vollmer’s candor exposes something painful. It is not too early in the war to discern nostalgic references to earlier wars. All wars refer back. Ships, planes, entire operations are named after ancient battles, simpler weapons, what we perceive as conflicts of nobler intent. This recon-interceptor is called Tomahawk II. When I sit at the firing panel I look at a photograph of Vollmer’s granddad when he was a young man in sagging khakis and a shallow helmet, standing in a bare field, a rifle strapped to his shoulder. This is a human moment, and it reminds me that war, among other things, is a form of longing. We dock with the command station, take on food, exchange cassettes. The war is going well, they tell us, although it isn’t likely they know much more than we do. Then we separate.

The maneuver is flawless and I am feeling happy and satisfied, having resumed human contact with the nearest form of the outside world, having traded quips and manly insults, traded voices, traded news and rumors—buzzes, rumbles, scuttlebutt. We stow our supplies of broccoli and apple cider and fruit cocktail and butterscotch pudding. I feel a homey emotion, putting away the colorfully packaged goods, a sensation of prosperous well-being, the consumer’s solid comfort. Vollmer’s T-shirt bears the word inscription. People had hoped to be caught up in something bigger than themselves,” he says. “They thought it would be a shared crisis. They would feel a sense of shared purpose, shared destiny. Like a snowstorm that blankets a large city—but lasting months, lasting years, carrying everyone along, creating fellow feeling where there was only suspicion and fear. Strangers talking to each other, meals by candlelight when the power fails. The war would ennoble everything we say and do. What was impersonal would become personal. What was solitary would be shared. But what happens when the sense of shared crisis begins to dwindle much sooner than anyone expected? We begin to think the feeling lasts longer in snowstorms. A note about selective noise. Forty-eight hours ago I was monitoring data on the mission console when a voice broke in on my report to Colorado Command. The voice was unenhanced, heavy with static. I checked my headset, checked the switches and lights. Seconds later the command signal resumed and I heard our flight-dynamics officer ask me to switch to the redundant sense frequencer. I did this but it only caused the weak voice to return, a voice that carried with it a strange and unspecifiable poignancy. I seemed somehow to recognize it. I don’t mean I knew who was speaking. It was the tone I recognized, the touching quality of some half-remembered and tender event, even through the static, the sonic mist. In any case, Colorado Command resumed transmission in a matter of seconds.

“We have a deviate, Tomahawk.” “We copy. There’s a voice.” “We have gross oscillation here.” “There’s some interference. I have gone redundant but I’m not sure it’s helping.” “We are clearing an outframe to locate source.” “Thank you, Colorado.” “It is probably just selective noise. You are negative red on the step-function quad.” “It was a voice,” I told them. “We have just received an affirm on selective noise.” “I could hear words, in English.” “We copy selective noise.” “Someone was talking, Colorado.” “What do you think selective noise is?” “I don’t know what it is.” “You are getting a spill from one of the unmanneds.” “If it’s an unmanned, how could it be sending a voice?” “It is not a voice as such, Tomahawk. It is selective noise. We have some real firm telemetry on that.” “It sounded like a voice.” “It is supposed to sound like a voice. But it is not a voice as such. It is enhanced.” “It sounded unenhanced. It sounded human in all sorts of ways.” “It is signals and they are spilling from geosynchronous orbit. This is your deviate. You are getting voice codes from twenty-two thousand miles. It is basically a weather report. We will correct, Tomahawk. In the meantime, advise you stay redundant.”

About ten hours later Vollmer heard the voice. Then he heard two or three other voices. They were people speaking, people in conversation. He gestured to me as he listened, pointed to the headset, then raised his shoulders, held his hands apart to indicate surprise and bafflement. In the swarming noise (as he said later) it wasn’t easy to get the drift of what people were saying. The static was frequent, the references were somewhat elusive, but Vollmer mentioned how intensely affecting these voices were, even when the signals were at their weakest. One thing he did know: it wasn’t selective noise. A quality of purest, sweetest sadness issued from remote space. He wasn’t sure, but he thought there was also a background noise integral to the conversation. Laughter. The sound of people laughing. In other transmissions we’ve been able to recognize theme music, an announcer’s introduction, wisecracks and bursts of applause, commercials for products whose long-lost brand names evoke the golden antiquity of great cities buried in sand and river silt. Somehow we are picking up signals from radio programs of forty, fifty, sixty years ago.

Our current task is to collect imagery data on troop deployment. Vollmer surrounds his Hasselblad, engrossed in some microadjustment. There is a seaward bulge of stratocumulus. Sun glint and littoral drift. I see blooms of plankton in a blue of such Persian richness it seems an animal rapture, a color change to express some form of intuitive delight. As the surface features unfurl I list them aloud by name. It is the only game I play in space, reciting the earth names, the nomenclature of contour and structure. Glacial scour, moraine debris. Shatter-coning at the edge of a multi-ring impact site. A resurgent caldera, a mass of castellated rimrock. Over the sand seas now. Parabolic dunes, star dunes, straight dunes with radial crests. The emptier the land, the more luminous and precise the names for its features. Vollmer says the thing science does best is name the features of the world. He has degrees in science and technology. He was a scholarship winner, an honors student, a research assistant. He ran science projects, read technical papers in the deeppitched earnest voice that rolls off the roof of his mouth. As mission specialist (generalist), I sometimes resent his nonscientific perceptions, the glimmerings of maturity and balanced judgment. I am beginning to feel slightly preempted. I want him to stick to systems, onboard guidance, data parameters. His human insights make me nervous.

“I’m happy,” he says. These words are delivered with matter-of-fact finality, and the simple statement affects me powerfully. It frightens me, in fact. What does he mean he’s happy? Isn’t happiness totally outside our frame of reference? How can he think it is possible to be happy here? I want to say to him, “This is just a housekeeping arrangement, a series of more or less routine tasks. Attend to your tasks, do your testing, run through your checklists.” I want to say, “Forget the measure of our vision, the sweep of things, the war itself, the terrible death. Forget the overarching night, the stars as static points, as mathematical fields. Forget the cosmic solitude, the upwelling awe and dread. I want to say, “Happiness is not a fact of this experience, at least not to the extent that one is bold enough to speak of it.

Laser technology contains a core of foreboding and myth. It is a clean sort of lethal package we are dealing with, a well-behaved beam of photons, an engineered coherence, but we approach the weapon with our minds full of ancient warnings and fears. (There ought to be a term for this ironic condition: primitive fear of the weapons we are advanced enough to design and produce.) Maybe this is why the project managers were ordered to work out a firing procedure that depends on the coordinated actions of two men—two temperaments, two souls—operating the controls together. Fear of the power of light, the pure stuff of the universe. A single dark mind in a moment of inspiration might think it liberating to fling a concentrated beam at some lumbering humpbacked Boeing making its commercial rounds at thirty thousand feet. Vollmer and I approach the firing panel. The panel is designed in such a way that the joint operators must sit back to back. The reason for this, although Colorado Command never specifically said so, is to keep us from seeing each other’s face. Colorado wants to be sure that weapons personnel in particular are not influenced by each other’s tics and perturbations. We are back to back, therefore, harnessed in our seats, ready to begin, Vollmer in his purple-and-white jersey, his fleeced pad-abouts.

This is only a test. I start the playback. At the sound of a prerecorded voice command, we each insert a modal key in its proper slot. Together we count down from five and then turn the keys one-quarter left. This puts the system in what is called an open-minded mode. We count down from three. The enhanced voice says, You are open-minded now. Vollmer speaks into his voiceprint analyzer. “This is code B for bluegrass. Request voice-identity clearance.”

We count down from five and then speak into our voiceprint analyzers. We say whatever comes into our heads. The point is simply to produce a voiceprint that matches the print in the memory bank. This ensures that the men at the panel are the same men authorized to be there when the system is in an open-minded mode. This is what comes into my head: “I am standing at the corner of Fourth and Main, where thousands are dead of unknown causes, their scorched bodies piled in the street.” We count down from three. The enhanced voice says, You are cleared to proceed to lock-in position. We turn our modal keys half right. I activate the logic chip and study the numbers on my screen. Vollmer disengages voiceprint and puts us in voice circuit rapport with the onboard computer’s sensing mesh. We count down from five. The enhanced voice says, You are locked in now.

As we move from one step to the next a growing satisfaction passes through me—the pleasure of elite and secret skills, a life in which every breath is governed by specific rules, by patterns, codes, controls. I try to keep the results of the operation out of my mind, the whole point of it, the outcome of these sequences of precise and esoteric steps. But often I fail. I let the image in, I think the thought, I even say the word at times. This is confusing, of course. I feel tricked. My pleasure feels betrayed, as if it had a life of its own, a childlike or intelligent-animal existence independent of the man at the firing panel. We count down from five. Vollmer releases the lever that unwinds the systems-purging disk. My pulse marker shows green at three-second intervals. We count down from three. We turn the modal keys three-quarters right. I activate the beam sequencer. We turn the keys one-quarter right. We count down from three. Bluegrass music plays over the squawk box. The enhanced voice says, You are moded to fire now.

We study our world-map kits. “Don’t you sometimes feel a power in you?” Vollmer says. “An extreme state of good health, sort of. An arrogant healthiness. That’s it. You are feeling so good you begin thinking you’re a little superior to other people. A kind of life-strength. An optimism about yourself that you generate almost at the expense of others. Don’t you sometimes feel this?” “(Yes, as a matter of fact.) “There’s probably a German word for it. But the point I want to make is that this powerful feeling is so—I don’t know—delicate. That’s it. One day you feel it, the next day you are suddenly puny and doomed. A single little thing goes wrong, you feel doomed, you feel utterly weak and defeated and unable to act powerfully or even sensibly. Everyone else is lucky, you are unlucky, hapless, sad, ineffectual and doomed.” (Yes, yes.) By chance, we are over the Missouri River now, looking toward the Red Lakes of Minnesota. I watch Vollmer go through his map kit, trying to match the two worlds. This is a deep and mysterious happiness, to confirm the accuracy of a map. He seems immensely satisfied. He keeps saying, “That’s it, that’s it.” Vollmer talks about childhood. In orbit he has begun to think about his early years for the first time. He is surprised at the power of these memories. As he speaks he keeps his head turned to the window. Minnesota is a human moment. Upper Red Lake, Lower Red Lake. He clearly feels he can see himself there. “Kids don’t take walks,” he says. “They don’t sunbathe or sit on the porch.” He seems to be saying that children’s lives are too well supplied to accommodate the spells of reinforced being that the rest of us depend on. A deft enough thought but not to be pursued. It is time to prepare for a quantum burn. We listen to the old radio shows. Light flares and spreads across the blue-banded edge, sunrise, sunset, the urban grids in shadow. A man and a woman trade well-timed remarks, light, pointed, bantering. There is a sweetness in the tenor voice of the young man singing, a simple vigor that time and distance and random noise have enveloped in eloquence and yearning. Every sound, every lilt of strings has this veneer of age. Vollmer says he remembers these programs, although of course he has never heard them before. What odd happenstance, what flourish or grace of the laws of physics enables us to pick up these signals? Traveled voices, chambered and dense. At times they have the detached and surreal quality of aural hallucination, voices in attic rooms, the complaints of dead relatives. But the sound effects are full of urgency and verve. Cars turn dangerous corners, crisp gunfire fills the night. It was, it is, wartime. Wartime for Duz and Grape-Nuts Flakes.

Comedians make fun of the way the enemy talks. We hear hysterical mock German, moonshine Japanese. The cities are in light, the listening millions, fed, met comfortably in drowsy rooms, at war, as the night comes softly down. Vollmer says he recalls specific moments, the comic inflections, the announcer’s fat-man laughter. He recalls individual voices rising from the laughter of the studio audience, the cackle of a St. Louis businessman, the brassy wail of a high-shouldered blonde just arrived in California, where women wear their hair this year in aromatic bales. Vollmer drifts across the wardroom upside down, eating an almond crunch. He sometimes floats free of his hammock, sleeping in a fetal crouch, bumping into walls, adhering to a corner of the ceiling grid. “Give me a minute to think of the name,” he says in his sleep. He says he dreams of vertical spaces from which he looks, as a boy, at—something. My dreams are the heavy kind, the kind that are hard to wake from, to rise out of. They are strong enough to pull me back down, dense enough to leave me with a heavy head, a drugged and bloated feeling. There are episodes of faceless gratification, vaguely disturbing.”

“It’s almost unbelievable when you think of it, how they live there in all that ice and sand and mountainous wilderness. Look at it,” he says. “Huge barren deserts, huge oceans. How do they endure all those terrible things? The floods alone. The earthquakes alone make it crazy to live there. Look at those fault systems. They’re so big, there’s so many of them. The volcanic eruptions alone. What could be more frightening than a volcanic eruption? How do they endure avalanches, year after year, with numbing regularity? It’s hard to believe people live there. The floods alone. You can see whole huge discolored areas, all flooded out, washed out. How do they survive, where do they go? Look at the cloud buildups. “Look at that swirling storm center. What about the people who live in the path of a storm like that? It must be packing incredible winds. The lightning alone. People exposed on beaches, near trees and telephone poles. Look at the cities with their spangled lights spreading in all directions. Try to imagine the crime and violence. Look at the smoke pall hanging low. What does that mean in terms of respiratory disorders? It’s crazy. Who would live there? The deserts, how they encroach. Every year they claim more and more arable land. How enormous those snowfields are. Look at the massive storm fronts over the ocean. There are ships down there, small craft, some of them. Try to imagine the waves, the rocking. The hurricanes alone. The tidal waves. Look at those coastal communities exposed to tidal waves. What could be more frightening than a tidal wave? But they live there, they stay there. Where could they go?” I want to talk to him about calorie intake, the effectiveness of the earplugs and nasal decongestants. The earplugs are human moments. The apple cider and the broccoli are human moments. Vollmer himself is a human moment, never more so than when he forgets there is a war. The close-cropped hair and longish head. The mild blue eyes that bulge slightly. The protuberant eyes of long-bodied people with stooped shoulders. The long hands and wrists. The mild face. The easy face of a handyman in a panel truck that has an extension ladder fixed to the roof and a scuffed license plate, green and white, with the state motto beneath the digits. That kind of face. He offers to give me a haircut. What an interesting thing a haircut is, when you think of it. Before the war there were time slots reserved for such activities. Houston not only had everything scheduled well in advance but constantly monitored us for whatever meager feedback might result. We were wired, taped, scanned, diagnosed and metered. We were men in space, objects worthy of the most scrupulous care, the deepest sentiments and anxieties.

Now there is a war. Nobody cares about my hair, what I eat, how I feel about the spacecraft’s decor, and it is not Houston but Colorado we are in touch with. We are no longer delicate biological specimens adrift in an alien environment. The enemy can kill us with its photons, its mesons, its charged particles faster than any calcium deficiency or trouble of the inner ear, faster than any dusting of micrometeoroids. The emotions have changed. We’ve stopped being candidates for an embarrassing demise, the kind of mistake or unforeseen event that tends to make a nation grope for the appropriate response. As men in war, we can be certain, dying, that we will arouse uncomplicated sorrows, the open and dependable feelings that grateful nations count on to embellish the simplest ceremony. A note about the universe. Vollmer is on the verge of deciding that our planet is alone in harboring intelligent life. We are an accident and we happened only once. (What a remark to make, in egg-shaped orbit, to someone who doesn’t want to discuss the larger questions.) He feels this way because of the war. The war, he says, will bring about an end to the idea that the universe swarms, as they say, with life. Other astronauts have looked past the star points and imagined infinite possibility, grape-clustered worlds teeming with higher forms. But this was before the war. Our view is changing even now, his and mine, he says, as we drift across the firmament.” Is Vollmer saying that cosmic optimism is a luxury reserved for periods between world wars? Do we project our current failure and despair out toward the star clouds, the endless night? After all, he says, where are they? If they exist, why has there been no sign, not one, not any, not a single indication that serious people might cling to, not a whisper, a radio pulse, a shadow? The war tells us it is foolish to believe.

Our dialogues with Colorado Command are beginning to sound like computer-generated teatime chat. Vollmer tolerates Colorado’s jargon only to a point. He is critical of their more debased locutions and doesn’t mind letting them know. Why, then, if I agree with his views on this matter, am I becoming irritated by his complaints? Is he too young to champion the language? Does he have the experience, the professional standing to scold our flight-dynamics officer, our conceptual-paradigm officer, our status consultants on waste-management systems and evasion-related zonal options? Or is it something else completely, something unrelated to Colorado Command and our communications with them? Is it the sound of his voice? Is it just his voice that is driving me crazy? Vollmer has entered a strange phase. He spends all his time at the window now, looking down at the earth. He says little or nothing. He simply wants to look, do nothing but look. The oceans, the continents, the archipelagoes. We are configured in what is called a cross-orbit series and there is no repetition from one swing around the earth to the next. He sits there looking. He takes meals at the window, does checklists at the window, barely glancing at the instruction sheets as we pass over tropical storms, over grass fires and major ranges. I keep waiting for him to return to his prewar habit of using quaint phrases to describe the earth: it’s a beach ball, a sun-ripened fruit. But he simply looks out the window, eating almond crunches, the wrappers floating away. The view clearly fills his consciousness. It is powerful enough to silence him, to still the voice that rolls off the roof of his mouth, to leave him turned in the seat, twisted uncomfortably for hours at a time.

The view is endlessly fulfilling. It is like the answer to a lifetime of questions and vague cravings. It satisfies every childlike curiosity, every muted desire, whatever there is in him of the scientist, the poet, the primitive seer, the watcher of fire and shooting stars, whatever obsessions eat at the night side of his mind, whatever sweet and dreamy yearning he has ever felt for nameless places faraway, whatever earth sense he possesses, the neural pulse of some wilder awareness, a sympathy for beasts, whatever belief in an immanent vital force, the Lord of Creation, whatever secret harboring of the idea of human oneness, whatever wishfulness and simplehearted hope, whatever of too much and not enough, all at once and little by little, whatever burning urge to escape responsibility and routine, escape his own overspecialization, the circumscribed and inward-spiraling self, whatever remnants of his boyish longing to fly, his dreams of strange spaces and eerie heights, his fantasies of happy death, whatever indolent and sybaritic leanings—lotus-eater, smoker of grasses and herbs, blue-eyed gazer into space—all these are satisfied, all collected and massed in that living body, the sight he sees from the window. “It is just so interesting,” he says at last. “The colors and all.” “The colors and all. “Human Moments in World War III” by Don Delillo, first published in Esquire, July 1983

The Interview.

13.01.20 | 12:18.

How are you. Well. You. Well. Shall we begin?

I remember being born. The under-carriage blitzering towards canarylight, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhOEKW8BG1Y 3:26).

Construction tremoring into a glass quay, light slowing. I can see reflectances of apartment blocks in the silicate – mirrorfreight. pastlight. We are approaching.

I see mother on the platform, yesterday. Or – shoreline, burning up now, – when leaving the train, please remember to take all of your belongings with you. 0.25x 3.24 – 3.33. 0.25x 3.24 – 3.33. there, look there, do you see them?

A little girl of seventeen in a mental hospital told me she was terrified because the Atom Bomb was inside her. That is a delusion. The statesmen of the world who boast and threaten that they have Doomsday weapons are far more dangerous and far more estranged from ‘reality’ than many of the people on whom the label ‘psychotic’ is affixed.

I like to imagine what it is like to live in this retinal lake of concrete.

There is something beautiful and sparse about the satelitte.

I have missiles in my mind.

The sun is crying.

The dance of inertia

the hothouse

the hothouse?

I’m cold.

Shall we take a break?

[Feel I.F. and I are getting somewhere. Canarylight episde has returned. Everything to date links but not sure where this. Close log]

The Wood.

Pressure converts to heat on my skin, I can feel the pixels crushing on my side.

He is in a dark room aside a projector that beams a satelitte waterworld into the far wall. He collects rain on the window sill.

The waterworld flickers into a timelapse, like a crushing retina. 2006. Deepset greens H6 the darks of treeline, farm holdings, river at low, anastomosing into a blue, faint siltline, forests north bleeding into strange red cutter line.

26.07.2011. light. solarine, imaged at 2300kmhr. The silt spit clear on blue waves like indents of a finger, roads, houses, developing films, bright whites at mouth of river, new bridge terraforming out inland, 29.10.2013. anotherbridge, mouthcrosser, siltline hiding by dark, forests northstill, less the large brights of reflectance concrete, larger than any house 2015. Greens to wheat yellow, reflecances coastal pierce, 22.08.2016. Curious dark rectangle, base of river mouth to sea, light blue dot atop mouth bridge, leisure pool, long roadup coast, ceasing before the red cutter. 6.5.2017. like filaments on a tendril, plots of home. 09.11.2019. darks of a late sunset pass. Colours of rooftop filaments, strangest yet, a large grey colossus, leviathan rectangular at the base as if concrete slabbed by an infernal giant.

He makes the notes fast, jotting the coordinates of this place 42°24’28.64″N | 41°33’7.60″E when he notices the man is no longer trancic by the window sill, feeling the rain with an outstretched hand but wired to a neural imaging kit. He looks serene blotted against the treeline of secondary rain. Then he stares directly at the soul of the waterworld wall and in a whisper, barely audible to his listenings, I am become death, destroyer of worlds. The screen blacks out, jerks. What is this place?

I see grey heat. It is warming up, I see Black Sea screaming into coastline, I see reds. I am become missile into the silent pixelline. Then a crushing sound of audial flicker. The waterworld opens on a transport ship, driving through a hulking storm, white spray breaking the dilapidating sound of hull creaking, Russian voices on the bridge. I see grey heat. He is doubled over staring at the waterworld. It cuts. There are three military blurs, russian, a man in a suit against a light blue. Ganmukhuri blue. A line against a line of men shouting, uniformed backing up. I feel a red line opening. He traces his hand outward toward the projector, cutting a slice in the damp air between the neuro-imaging kit and projector. The wall cuts to the sound of techno, and a woman in a pink miniskirt, fishnet vest and nipple tassles dancing in a sea of individuals against calm watery background. Ganmukhuri blue. An orange buoy bobs twenty metres out.

Can you see it. The secret world beneath the waves. He remembers the timelapse now, so many waves washing over the next in a silence of years, the ant-sphere rustling on the filaments of tendrils, and bridges against the tenements of time. The man is hot to reach out to when he screams, almost screams a single word, like wiring.

He is whirring across Black Sea pressure lines… to Novorossisyk…a timelapse… I’m jotting he’s plunging… blue roofs, blue, blue… then videos…russians/chinese…a VR lorry…glitching…

The rain is wearing off when he disconnects the neuro-imaging kit, and asks he visit him again. He agrees, leaving on the track through the darkening deciduouses back past the old train-lines to the city.

1956 Tbilisi, Poznan, Budapest

Pynchon's Berlin, soul dyadic split of von braun west, korolev east

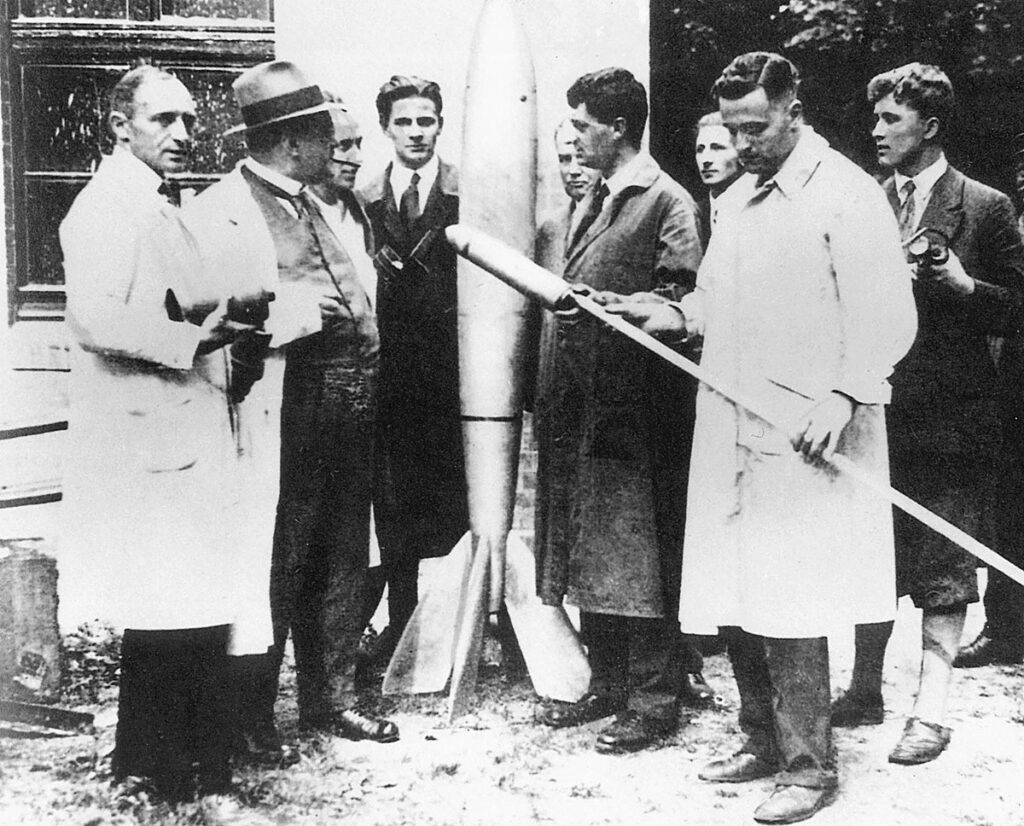

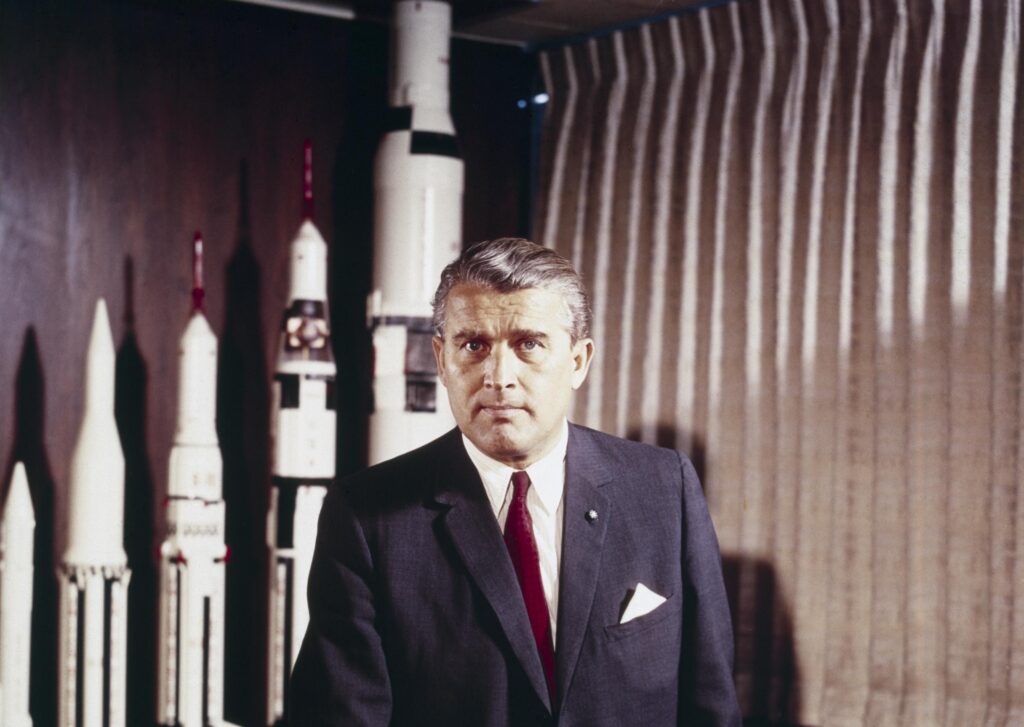

“Not for the first time, Wernher von Braun must have wondered if coming to America had been a mistake. After all, he had chosen the United States, among all the countries who had vied for his services, because he had thought that only America had the resources and foresight to pursue rocket technology. Even before the war had ended, von Braun had gathered his key engineers to discuss which Allied nation offered the best hope for continuing their careers. “It was not a big decision,” recalled the physicist Ernst Stuhlinger, one of those present during the defection discussions. “It was very straightforward and immediate. We knew we would not have an enviable fate if the Russians would have captured us.” The French had been discounted as strutting losers. The British had fought bravely, but the United Kingdom was small and no longer the power it had once been. West Germany would have strict limits placed on its military programs. That left only the United States. But the America that greeted von Braun when he first stepped off a military cargo plane in Wilmington, Delaware, in September 1945 was not the place he had expected. At the time, his mere presence on U.S. soil was deemed sufficiently sensitive that it was kept secret for over a year. He cleared no customs and passed through no formal passport controls. The paper trail documenting his entry was sealed in an army vault, along with his incriminating war files; his Nazi Party ties, his depositions denying his involvement in slave labor, and his three SS promotions remained classified until 1984, seven years after his death. ”

When Germany’s leading scientists began arriving under military escort at Fort Bliss in the fall of 1945, it is not difficult to imagine the culture shock they must have experienced. Brown dusty plains stretched to the east as far as the eye could see. The desert was unbroken save for the occasional tumbleweed, buzzard, and cactus, and it baked at over a hundred degrees for most of the year. To the west rose the jagged red peaks of the Sangre de Cristo, or Christ’s Blood, Mountains. To the south ran the Rio Grande and the squalid pueblos of Mexico. At night, an impregnable blackness descended over the land, Stuhlinger recalled. And during the day, the hot Texas sky broiled a deep blue completely alien to any European. “To my continental eyes,” von Braun later confessed, “the sight was overwhelming and grandiose, but at the same time I felt in my heart that I would find it very difficult ever to develop a genuine emotional attachment to such a merciless landscape.” Fort Bliss was a far cry from the resplendent accommodations von Braun had grown accustomed to in his German headquarters on the island of Peenemünde, where the sand was confined to pleasant beaches, his sailboat and personal Messerschmitt plane were always at the ready, and the maître d’ at the research center’s four-star Schwabes Hotel stocked the wine cellar with the finest vintages seized from France. ”At Fort Bliss, the Officers’ Club was off-limits to the Germans. They had to build their own clubhouse in a storage shed, stocking it with homemade furniture and a bar they cobbled together from spare planks. Sometimes von Braun’s brother Magnus, who had been a supervisor at Mittelwerk, played the accordion. At other times, after a few rounds of tequila, when the monotony, seclusion, and language lessons got to them, they crept through a hole in the fence to look at the stars in the desert sky. “Prisoners of peace” was how they referred to themselves. But at least they were out of reach of the prosecutors and the war crimes tribunals in Europe that were meting out justice for the slaughter of slave laborers at Mittelwerk, among a host of other Nazi atrocities.

A year, and then two, passed aimlessly. Resources at Fort Bliss were as rare as rain. Only $47 million had been allocated in 1947 for total U.S. missile development, and that left precious little for the Germans. Fort Bliss’s miserly quartermaster turned down a request by von Braun’s brother for linoleum to cover the cracks between boards in the wood floor of the hut where delicate gyroscopes were assembled. He also denied a requisition for a high-speed drill. “Frankly, we were disappointed,” von Braun recalled years later. “At Peenemünde we had been coddled. Here you were counting pennies . . . and everyone wanted military expenditures curtailed. Von Braun bubbled with ideas for new rockets. But his every proposal was shot down. Nor was anyone particularly interested in his ideas for space travel either. He sent a manuscript on exploring Mars to eighteen publishers in New York, and eighteen rejection letters wended their way back to the Fort Bliss postmaster. Adding insult to injury, von Braun now had to report to a twenty-six-year-old major whose sole technical background was an undergraduate engineering degree. When von Braun was twenty-six, thousands of engineers had answered to him. […] The U.S. government had gone through a great deal of trouble to ensure that no other power acquired the services of Nazi Germany’s rocket elite. Retaining “control of German individuals who might contribute to the revival of German war potential in foreign countries,” as a State Department memo inelegantly put it, had been the primary justification for the 1947 decision to make von Braun’s temporary stay in America more permanent. Even if the United States didn’t need him right now, Washington wanted to make certain no one else got his expertise. Due to their “threat to world security,” the Germans couldn’t be repatriated. To a frustrated von Braun, it seemed that the United States had dumped him and his team in deepest Texas and forgotten all about them. “We were distrusted aliens living in what for us was a desolate region of a foreign land,” he recalled. “Nobody seemed much interested in work that smelled of weapons.

Von Braun might have languished indefinitely under the hot Texas sun if not for the actions of two men: Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and North Korea’s Communist leader, Kim II Sung. McCarthy’s Red-baiting reign of terror—when everyone from J. Robert Oppenheimer to what seemed like half of Hollywood was accused of Communist sympathies—inadvertently helped to rehabilitate von Braun. The only skeletons in his closet were Nazi skeletons, and the Reich was yesterday’s enemy. Berlin was no longer the seat of evil. The divided city had been transformed into a symbol of freedom by the massive airlift orchestrated by Symington and LeMay in 1948, when three hundred thousand sorties were flown, delivering food and medicine during Stalin’s yearlong siege of West Berlin. The cold war by then had begun in earnest, and a new adversary had replaced fascism as an ideological threat to the American way of life. The threat was magnified a thousandfold the following year, when Moscow detonated its first atomic bomb. The era, grumbled LeMay, “when we might have completely destroyed Russia and not even skinned our elbows doing it” was over. A few months later, the revolutionary cancer spread to China, further whipping up domestic paranoia in the United States. Suddenly, any American who had ever attended a Marxist meeting in the 1930s, or dated someone who had, was potentially a security risk. Immigrant scientists, with their top-secret clearances and Eastern European backgrounds, were especially vulnerable. After Mao’s victory, the blacklist was expanded to include Chinese-born American researchers. Tsien Hsue-shen, one of the founders of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech and a pioneer in the field of American rocketry, was arrested and deported to China. (Documents would later reveal that he had been innocent of the spying charges, prompting one military historian to call the affair the “greatest act of stupidity of the McCarthyist period. . . . China now has nuclear missiles capable of hitting the United States in large part because of Tsien.”)

Von Braun, however, was above reproach. For five years the FBI and army intelligence had monitored his every move, read his correspondence, and listened to his telephone conversations. Nothing more untoward than the suspect sale of some undeclared silver by his brother Magnus had ever been uncovered. By the summer of 1950, the political climate had changed sufficiently enough for von Braun to come out of purgatory. What’s more, his services were finally needed again. On the night of June 25, 1950, Kim II Sung’s North Korean forces crossed the thirty-eighth parallel, threatening to overrun South Korea. This time President Truman decided to draw the line. Three weeks later von Braun received his first meaningful commission, the Redstone. The Redstone performed flawlessly during its 1953 tests, and Walt Disney came calling the following year with an intriguing television offer. “Was the handsome von Braun interested in hosting the “Man in Space” segments of the Tomorrowland programs? … It was thus from the odd pairing of Mickey Mouse and a former SS major with a Teutonic Texas twang that most Americans first heard of the futuristic concept of an earth-orbiting satellite. Disney himself introduced the inaugural Tomorrowland program on March 9, 1955. The show attracted 42 million viewers and made von Braun a star. With his youthful good looks, broad shoulders, and perfect blend of boyish enthusiasm and European erudition, von Braun quickly became America’s space prophet, a televangelist leading audiences on the scientific conquest of distant planets. The country was enthralled by the endless possibilities unleashed by jet travel and the splitting of the atom. Modernism swept architecture, automobile, and furniture design, where styles were sharp, angular, and edgy. Engine Charlie’s General Motors incorporated the fast, futuristic themes in its famous Motorama car shows, which featured Delta-wing designs, high fins, and space-bubble taillights. Cool, crisp colors announced the new era: pale greens, baby blues, pastel yellows, and deep, pile-rug whites. Earth tones were out; glass and stainless steel were in. At the movies, aliens reigned as Invaders from Mars and War of the Worlds dominated the box office. “In fashion, the look was tapered, sleek, and hurried. In music, the new sound was rushed, the rapid-fire rhythm of rock and roll. Speed was the essence of the jet age, and it found expression even in the national diet. In 1955, the entrepreneur Ray Kroc franchised his first two McDonald’s restaurants. He called them fast-food outlets. The Disney series had tapped into this headlong dash toward the future and inflamed the imagination of Americans in much the same way that the writings of Hermann Oberth and the films of Fritz Lang had ignited the amateur rocketry craze in Germany in the late 1920s that eventually produced the V-2. But the space craze that swept the nation in the mid-1950s did not translate into political support for space programs. Lawmakers had more earthbound and immediate concerns. Space was the distant domain of dreamers and science fiction writers.” “Until 1954, cumulative federal spending on satellite research in the United States amounted to $88,000. And even this sum was thought excessive. When von Braun that same year offered to launch a satellite using a modified Redstone missile for less than $100,000, his request for the additional funding was flatly denied. If money was any indication of political interest, satellite and space exploration did not even register on radar screens in the nation’s capital until 1955, when the Soviet Academy of Sciences announced that it would try to send a craft into orbit as part of the planned International Geophysical Year. (The pledge was meaningless, however, until Khrushchev and the Presidium got on board the following year.) The IGY was a science Olympics of sorts that had its origins in the nineteenth-century Arctic exploration races. Held every fifty years to encourage scientific exchange on the physical properties of the polar regions, it had expanded its brief to cover the planet’s skies, oceans, and ice caps. A few weeks prior to the IGY’s 1955 convention in Rome, which set July 1, 1957, as the start of the next Geophysical Year, Radio Moscow announced that the Soviet Union would launch scientific instruments into space to measure such phenomena as solar radiation and cosmic rays. In response, the National Academy of Sciences promptly declared that the United States would also send up a satellite to study the earth’s protective cocoon. “The atmosphere of the earth acts as a huge shield against many types of radiation and objects that are found in outer space,” the academy press release stated, somewhat dryly. “In order to acquire data that are presently unavailable, it is most important that scientists be able to place instruments outside the earth’s atmosphere in such a way that they can make continuing records about the various properties about which information is desired. Behind the seemingly benign facade of the announcements, both the United States and the Soviet Union had ulterior motives for participating in the IGY. Each was looking for a peaceful, civilian excuse to test the military potential of its hardware—how air drag, gravitational fields, and ion content could affect missile trajectories; how the ionosphere affected communications; how orbital decay worked; and so on. There was another, equally important consideration: a research satellite blessed by the international scientific community would set the precedent for an “open skies” policy where sovereign airspace did extend beyond the stratosphere. This, more than anything, argued James Killian at the Office of Defense Mobilization, justified the military’s support for the IGY program. Excerpt From: Matthew Brzezinski. “Red Moon Rising”. Apple Books.

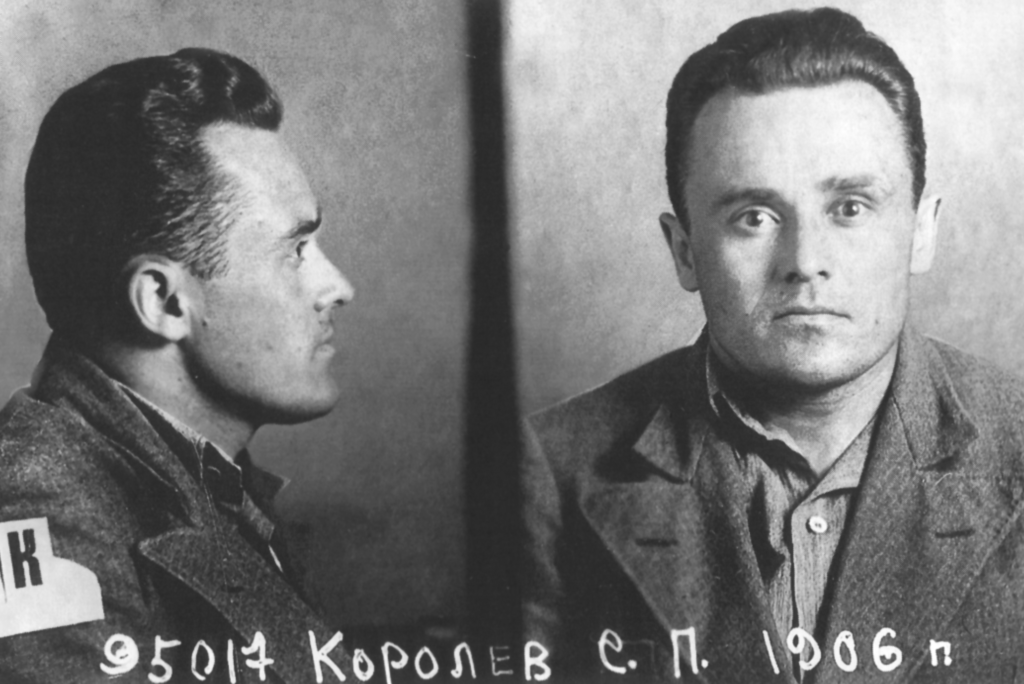

Glushko loved the ballet and classical music, and he enjoyed long, languid meals at Moscow’s few fine restaurants. Korolev had no interests outside of rockets and viewed food as fuel. “He ate very quickly,” a fellow OKB-1 engineer recalled. “After finishing the food on his plate, he would wipe it clean with a piece of bread, which he subsequently put in his mouth. He even scooped up the crumbs and ate them. Then he licked all his fingers. The people around him looked on with amazement until someone volunteered that this was a habit he had developed during his years in prison and in labor camps. No one who had ever gone through the gulag emerged physically or psychologically unscathed. Though the Chief Designer rarely spoke of it, the Great Terror had left indelible marks on both his body and his soul. Even decades later, he could remember the minutest details of his arrest in 1938: the rasp of the needle on the gramophone that kept churning its spent record while the men in black ransacked his apartment; the sound of the trolleybus bells ringing six stories below; the hushed whimper of his three-year-old daughter, Natalia as she clung to her terrified mother. At the Kolyma mines, the most notorious of Stalin’s Siberian death factories, his days had started at 4:00 AM, in sixty-below-zero darkness that lasted most of the year, conditions that killed a third of the inmates each year. The criminals administered justice in Kolyma, beating the political prisoners mercilessly if they dropped a pickax or spilled a wheelbarrow or missed their quota. They stole their food and clothes, and pried out the gold fillings the greedy guards had overlooked. Within a few months of his arrival at Kolyma, Korolev was unrecognizable. He could barely walk or talk; toothless, his jaw was broken, scars ran down his shaven head, and his legs were swollen and grotesquely blue. Scurvy, malnutrition, and frostbite had started their lethal assault and he seemed destined to die. And yet, like millions of other purge victims, he still held out the hope that Stalin himself would realize that a terrible mistake had been made and free him. “Glushko gave testimonies about my alleged membership of anti-Soviet organizations,” Korolev wrote Stalin in mid-1940, naming several others he claimed had borne false witness against him. “This is a despicable lie. . . . Without examining my case properly, the military board sentenced me to ten years. . . . My personal circumstances are so despicable and dreadful that I have been forced to ask for your help.” Korolev’s mother also petitioned Stalin directly. “For the sake of my sole son, a young talented rocket expert and pilot, I beg you to resume the investigations. But their letters, like the countless other pleas of assistance with Siberian postmarks that reached the Kremlin daily, went unanswered. What saved Korolev, ultimately, was Hitler’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union and the sudden drastic need for skilled military engineers. Transferred to one of the special Sharaga minimum-security technical prison institutes that Beria had set up to exploit jailed brainpower, Korolev slowly recovered, until, at war’s end, he was released and sent to Germany to parse the secrets of the V-2. Had Glushko and Korolev forgotten, or forgiven each other? Or had they simply buried their simmering recriminations and resentments beneath a thin veneer of civility? Another factor complicating their reconciliation was the persistent rumor that Korolev had engaged in a long-running affair with Glushko’s sister-in-law. The alleged romance—a source of contention among contemporary Russian historians—had predated the purges and apparently resumed in 1949, as the Chief Designer’s first marriage was falling apart. Whether Glushko knew about it, or how he felt about his brother’s deception and humiliation at the hands of his rival, is not a matter of the historical record. The only thing clear amid the unanswered questions was that Korolev and Glushko needed each other and had to find a way to work together. The first hurdle the pair faced in the wake of the Presidium visit was rocket power. To fling a five-ton thermonuclear warhead 5,000 miles, Korolev had calculated that he needed more than 450 tons of thrust. This represented a tenfold increase over the R-5 intermediate-range ballistic missile, whose RD-103 booster had already strained the limits of single-engine capacity. (Glushko had experimented with a mammoth 120-ton thrust engine, the RD-110, but the project had been abandoned.) To meet Korolev’s vastly increased power requirement, the R-7 would have to be powered by five separate rockets, bundled like a giant Chinese fireworks display.

The R-7’s rescheduled March 1957 test-launch deadline came and went, and Sergei Korolev was still not ready. He was becoming increasingly irritable, more prone to terrorizing his staff with his infamous flare-ups, and he wielded both the stick and the carrot to motivate his engineers. Breakthroughs were rewarded with on-the-spot bonuses, wads of rubles that Korolev kept in an office safe for just such a purpose. The most significant achievements earned holidays to Black Sea resorts or even the most sought-after commodity in the entire Soviet Union: the keys to a new apartment. Like all large factories and institutes, OKB-1 was responsible for housing its employees. For young and especially newlywed scientists living in dormitories without privacy, few incentives matched the prospect of skipping to the front of the long waiting list for a place of their own. “The capitalist approach was paying dividends, as glitches were progressively ironed out. Valentin Glushko had wanted no part in making modifications to the steering thrusters, so they were completed in-house at OKB-1. The addition of the tiny directional thrusters also solved the problem of postimpulse boost; the R-7’s main engines could now be shut down a fraction of a second early to compensate for residual propellant, while the little thrusters could be fired to adjust speed and position at the critical aiming, or “sweet,” point, as guidance specialists called cutoff. A backup radio-controlled radar guidance system was also installed to augment the accuracy of the onboard inertial gyroscopes. Boris “Chertok supervised the duplicate system, which had involved building nine tracking stations deep in the Kazakh desert over the first 500 miles of the R-7’s trajectory route, and another six stations within a 90-mile approach to the target area in the Kamchatka Peninsula, 4,000 miles farther. As the missile would fly over the first nine stations, radar would pick it up, plot whether it was on course, and send back telemetry signals for any needed adjustments to trim, yaw, or pitch in what essentially was a very large and costly version of amateur modelers flying radio-controlled airplanes. But with the R-7, the action would unfold at speeds in excess of 17,000 miles per hour and span many time zones in a matter of minutes. The reentry problem, as Korolev would discover, was far from licked, but by late April the Chief Designer felt sufficiently confident that he moved his entire operation to the secret facility that had been built for the R-7 in Kazakhstan to finally take the ICBM out for its long-delayed test flight.

Originally known as Tyura-Tam and eventually as Baikonur (in yet another instance of Soviet misdirection), the installation was one of the most closely guarded secrets in the Soviet Union. Correspondence to it was simply addressed to Moscow Post Office Box 300, and it figured on no map. The military construction crews that had built it had been rotated in short, highly compartmentalized shifts, and never told what they were doing in the middle of the broiling Kazakh desert, where temperatures soared to 135 degrees in summer and plunged to 35 below in the short, merciless winter. Dust storms clogged machinery with salty sand particles blown across the central Asian steppe from the Aral Sea. For hundreds of miles, there was not a single tree to offer shade or firewood. Soldiers slept in tents crawling with scorpions, and water had to be trucked in. “Besides the benefit of seclusion, the Tyura-Tam site had been selected because of the R-7’s guidance problems. Tracking stations could be built in the depopulated area along the route to Siberia, and rocket engineers didn’t have to worry about spent boosters falling on urban centers. A major rail spur also happened to run nearby, easing the transport of missile parts and building materials. The pace of construction at Tyura-Tam had been so frenetic, so filled with accidents and setbacks, that the young military officer responsible for erecting the Soviet Union’s first nuclear ICBM launch site had gone crazy and been carted away to a psychiatric ward. Only the rudimentary infrastructure had been completed in time for testing: a huge assembly hangar connected by rail to a fire pit the size of a large quarry to absorb the flames at liftoff; several underground propellant storage tanks; a cement bunker blockhouse; and a 15,000-square-foot launch platform “erected out of sixteen massive bridge trusses. Otherwise, and in every direction, there were only shifting dunes and the shimmering heat waves of the sun reflecting off the sand. There had been no time to build housing, cafeterias, recreation halls, laboratories, or even lavatories. Scientists lived four to a compartment in train cars that had been built in East Germany after the war and equipped with special labs for the storage and testing of delicate rocket components. The rocket was cleared for liftoff just after 7:00 PM MOSCOW time on May 15. The massive engines fired, the Tulip launch stand worked perfectly, and the R-7 rose to the whooping cheers of assembled engineers and VIPs. But ninety-eight seconds into the flight something went terribly wrong. The missile crashed, scattering debris over a 250-mile radius.

Back in Moscow, Sergei Khrushchev recalled the phone ringing after dinner at the family’s mansion in Lenin Hills. It was the white line, the German-made phone used for important government business. “That was Korolev,” said Nikita Khrushchev, looking particularly gloomy as he hung up. “They launched the R-7 this evening. Unfortunately it was unsuccessful. Korolev, though, was upbeat. First launches almost always failed. That had been the rule with the R-l, the R-2, and the R-5. And he had reason to feel optimistic: for the first minute and a half, the R-7 had performed flawlessly. The trouble had been with one of the peripheral boosters, block D, which had caught fire shortly before separation. The suspected cause of the explosion was excessive vibrations, what was known as the Pogo effect. Korolev and his team would figure out exactly what had happened and fix the glitch. Next time, he was certain, his missile would make it all the way to the target zone in Kamchatka, almost 5,000 miles away on Siberia’s Pacific coast. For a long, hot month, they tinkered. At last, on June 9, another R-7 was wedged into the Tulip launch stand. Voskresenskiy supervised all the preparations. Korolev trusted him implicitly, and on more than one occasion he had proven his loyalty and courage. Once, when a launch had misfired and the live warhead had been dislodged from its missile, dangling precariously over the pad, everyone had frozen in panic. But Voskresenskiy had calmly told Korolev, “Give me a crane, some cash, five men of my choosing, and three hours.” With wads of vodka-walking-around money bulging out of their pockets, Voskresenskiy’s men safely dismantled the one-ton warhead, after which they got royally drunk. “Like a great many test pilots and other people who push safety envelopes for a living, Voskresenskiy was deeply superstitious. So when the next R-7 failed to start, not once, not twice, but on three consecutive days before sputtering out with a smoky cough on the launchpad on June 11, Voskresenskiy decided it was cursed. “Take it away,” he ordered. “I never want to see it again.” The blighted rocket was hauled away in disgrace.

A dark, defeated mood settled over the exhausted R-7 team. They hadn’t seen their families in several months. They were working round the clock, seven days a week, and people were getting sick from the long hours and unremitting worry. Chertok came down with a strange ailment with similar symptoms to radiation poisoning. Eventually he would have to be medically evacuated to Moscow. Korolev developed strep throat and had to take frequent penicillin shots. His health had never fully recovered from the ravages of the camps, and he frequently took ill. “We are working under a great strain, both physical and emotional,” he wrote his second wife, Nina. “Everyone feels a bit sick. I want to hug you and forget about all this stress.” “Korolev had met Nina Kotenkova at OKB-1, where she served as the institute’s English-language specialist, translating Western scientific periodicals. It was through her that the Chief Designer had kept abreast of Wernher von Braun’s writings and exploits in the American media, and in the flush of lonely nights spent jointly hunched over the pages of Popular Mechanics they had fallen in love. Korolev had still been married to his first wife, Ksenia, when they had met, and their affair had led to a bitter divorce and estrangement from his teenage daughter, Natalia, who for years refused to see him and would never agree to speak to Nina. From his monastic hut at Tyura-Tam, a cabin without running water and only a bare lightbulb to illuminate the lonely gloom, Korolev wrote his daughter weekly, begging for her forgiveness. He tried calling on her twenty-first birthday, but she hung up on him. “It hurts me so much,” he told Nina. Even at the best of times, Tyura-Tam was a dispiriting place. But with two consecutive failures, growing friction between the different design bureaus over responsibility for the myriad malfunctions, and Moscow becoming increasingly irritated, the atmosphere was downright foreboding as Korolev lined up a third R-7 for launch on July 12. This time the countdown went uninterrupted, the engines all fired properly, and the missile lifted off without a hitch at 3:53 PM. Thirty-three seconds later it disintegrated. The strap-on peripheral boosters had separated early.

Watching the four flaming boosters slowly sail down into the desert just four humiliating miles from the launchpad, Korolev dejectedly shook his head. “We are criminals,” he said. “We just burned away [the financial equivalent of] an entire town.” “Fear now descended on the despondent scientists. The Soviet Union was not so far removed from the Stalinist era to presume that punishment might not be meted out for the catastrophic and costly failures. “What can they do to us?” a frightened Chertok asked Konstantin Rudnev, the deputy minister of armaments. “They are not going to jail us, or send us to Kolyma?” Though it didn’t appear that the U.S. missile program was going to overtake the Soviets anytime soon, for some reason Korolev was fixated on the notion that von Braun was going to launch a satellite at any moment. The Americans are on the verge, he kept telling anyone who would listen, and he obsessively scoured Nina’s translations of Western publications for any hint that might betray America’s orbital intentions.

The Chief Designer’s manic paranoia on the subject had begun to irk his exhausted colleagues at Tyura-Tam, where tempers were flaring and the blame game among the designers was reaching new heights. They had now had five failures, and everyone was pointing fingers. “Despite Korolev’s attempt to spread the bureaucratic blame, the message from Moscow was clear: it was his rocket and his responsibility, and the State Commission on the R-7 was getting ready to recommend pulling the plug. Korolev’s career, his dreams, his future—possibly even his freedom—hung by a thread. He was alone, literally sick and tired, stuck in the hellish Kazakh desert, and the vultures were circling. For the supremely self-confident Korolev, it was an unaccustomed and frightening predicament. “When things are going badly, I have fewer ‘friends,’” he wrote Nina with uncharacteristic humility. “My frame of mind is bad. I will not hide it, it is very difficult to get through our failures. . . . There is a state of alarm and worry. It is a hot 55 degrees [131 Fahrenheit] here. Despite Korolev’s attempt to spread the bureaucratic blame, the message from Moscow was clear: it was his rocket and his responsibility, and the State Commission on the R-7 was getting ready to recommend pulling the plug. Korolev’s career, his dreams, his future—possibly even his freedom—hung by a thread. He was alone, literally sick and tired, stuck in the hellish Kazakh desert, and the vultures were circling. For the supremely self-confident Korolev, it was an unaccustomed and frightening predicament. “When things are going badly, I have fewer ‘friends,’” he wrote Nina with uncharacteristic humility. “My frame of mind is bad. I will not hide it, it is very difficult to get through our failures. . . . There is a state of alarm and worry. It is a hot 55 degrees [131 Fahrenheit] here.”

Sergei Korolev hadn’t had reason to laugh for a long time. But he was in unusually high spirits on the August morning he visited Boris Chertok at Moscow’s Burdenko military hospital. “Okay, Boris,” he cheerfully chided Chertok. “You continue playing sick, but don’t stay out for too long.” A half dozen jubilant engineers crowded around Chertok’s bed, teasing and poking their infirm colleague. The suspected radiation poisoning had turned out to be simply an exotic Kazakh bug that manifested similar symptoms. “This is the best medication,” assured Leonid Voskresenskiy, the daredevil chief of testing, pulling a bottle of cognac out of a bag. “So,” he said, once Korolev had finished his pep talk and excused himself on the grounds of an important meeting. “Here’s the pickle we’re in. Everyone congratulates us, but nobody other than us knows what’s really going on. The rocket, as Chertok already knew, had finally worked. Korolev had been given one final chance to prove himself, and at 3:15 PM on August 21, the R-7 had flown all the way to Kamchatka, landing dead on target next to the Pacific Ocean. Korolev had been so relieved, so euphoric, that he had stayed up until 03:00am the next morning, jabbering away excitedly about the barrier they had just broken. There was a slight hitch, however. The heat shield had failed, and the dummy warhead had been incinerated on reentry. Apparently, the nose cone dilemma hadn’t been solved after all. And without thermal protection, the R-7 was not an ICBM, just a very large and expensive rocket. That was why Korolev had just rushed off to meet with a group of aerodynamic specialists: to see if they had any solutions to what Voskresenskiy called “Problem Number One.

“We need to take a break to make radical improvements on the nose cone,” Voskresenskiy told Chertok, leaning closer and lowering his voice to a mock-conspiratorial whisper. “While we’re working on it, we’ll launch satellites. That’ll distract Khrushchev’s attention from the ICBM.” On the morning of August 28, 1957, the same day that Boris Chertok and Leonid Voskresenskiy would sip cognac and swap conspiratorial jokes at the Burdenko military hospital in Moscow, ground crews at a secret airstrip outside Lahore, Pakistan, readied a mysterious plane for takeoff. The black, single-engine craft bore little resemblance to anything that had ever taken to the skies before. As with a glider that had been retrofitted for powered flight, its slender silhouette defied conventional design. The wings were disproportionately elongated and dog-eared at the tips. While the ground crews made their preflight rounds, another group of technicians, distinguished by their white gloves, fidgeted in a bay under the single-seat cockpit. There, next to three small-diameter portholes that contained the most sophisticated photographic lenses ever devised, they loaded a 12,000-foot-long spool of high-resolution Kodak film. The custom-made film and 500-pound Hycon camera were the only outward clues as to the plane’s true purpose. Otherwise, it had no markings, identification numbers, or insignias. No running lights winked under its dark fuselage, which had been painted dull black to better blend in with the night sky. Nowhere in its equally anonymous innards was there a manufacturer’s seal or anything else that would betray that the CL-282 Aquatone had been assembled at the top-secret Lockheed Skunkworks plant in Burbank, California.”

Officially, the CL-282—or the U-2, as it would eventually be called—did not exist. Neither did the pilot, E. K. Jones, who was going through his own preflight routine in a small, barrack-style building near the runway. Like the twenty-man Quickmove mobile maintenance team and the fuel drums they had brought with them, Jones had been flown in the day before from the U-2 main staging base in Adana, Turkey, to minimize American exposure to prying Pakistani eyes. At 4:00 AM a doctor measured his temperature, pulse, and blood pressure and examined his ears, nose, and throat for signs of infection. The medical exam was a formality; like every one of the two dozen U-2 pilots on the CIA’s payroll, Jones was in excellent physical condition. Bissell’s boys operated under the cover of high-altitude weather research. Like the unmarked planes they flew, Jones and his fellow aviators carried no identification papers or dog tags, and no regimental crests or badges adorned their flight suits.” “Shortly before 5:00 AM in Lahore, E. K. Jones was “integrated” into a fully pressurized suit and began breathing pure oxygen for the hour prior to takeoff. He did this to lower the nitrogen level in his blood to avoid getting the bends, in much the same way deep-sea divers decompressed in special chambers before surfacing—only in reverse, as he would be climbing rather than descending. The pressurized suit Jones “wore would keep his body from boiling and exploding at the altitude he would travel, a height where the air is so thin that atmospheric pressure drops to one-twenty-eighth that of sea level.”

Jones would not be traveling into space. But at the height the U-2 reached, he would skirt the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, and his special orange flight suit would keep the gases in his intestines from expanding and bursting like overinflated balloons if the U-2’s cabin pressure suddenly failed or if he had to parachute out of the plane. At the Lovelace Clinic near Albuquerque, where pilot prospects were sent, Bissell had devised a very elaborate psychological profile of the sort of men he sought: patriots, naturally, but people who liked living on the edge, for whom death was not a deterrent.

Bissell’s pilots had to meet one other critical criterion: they had to be exceptionally gifted airmen, because the U-2 was among the most difficult aircraft to fly. Simply positioning the plane for takeoff required great skill. Its turning radius of 300 feet was nearly ten times that of a “regular fighter jet, and visibility from the cockpit was virtually nonexistent. The plane had another troublesome characteristic. At high altitude, where even the U-2’s 200-foot wingspan barely generated lift in the thin air, its 505-miles-per-hour stall speed and 510-miles-per-hour maximum speed converged in what pilots called the “coffin corner,” leaving a scant margin of error. On landing, the massive wings—three times longer than the sixty-foot plane itself—also required deft handling. To get the U-2 down safely, the pilot had to stall the plane precisely two feet off the tarmac, exactly on the center line, and keep the massive wings off the ground by flying the aircraft down the runway in perfect equilibrium. Soon the U-2 was a speck in the Pakistani sky as it continued its ascent beyond the range of telephoto lenses. At 70,000 feet, as the outside temperature dropped to 160 degrees below zero, Jones leveled the U-2. The skies above blackened and filled with stars, and over the horizon Jones could see the blue and white curvature of the earth. Beneath him, the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush unfolded like an accordion; beyond that, Afghanistan, and the endless orange plains of Soviet central Asia. He pointed the plane north and crossed into Soviet airspace.” “The first U-2 mission over the Soviet Union had coincided with a goodwill visit by Nikita Khrushchev to Spaso House, the U.S. ambassador’s official residence in Moscow, on July 4, 1956. While Khrushchev toasted America’s 180th birthday with Ambassador Charles Bohlen, a U-2 snapped aerial photographs of the Kremlin before heading off to photograph the naval and air bases around Leningrad. Allen Dulles had worried about the timing of the mission and “seemed somewhat startled and horrified to learn that the flight plan”—which had included a pass over Poznan, the scene of Polish rioting only a few days earlier—“had covered Moscow and Leningrad,” Bissell recalled. “Do you think that was wise the first time?” Dulles asked. “Allen,” Bissell replied, “the first time is always the safest,” since the Soviets were not expecting the mission. But he was wrong. Bissell had presumed that because the U-2 had evaded most American radars during its test, the Soviets would not be able to pick it up either. What he didn’t realize was that the USSR had recently deployed a new generation of radar capable of tracking planes at much higher altitudes.

Khrushchev had immediately been informed of the flight and viewed the timing of the incursion as a personal affront. Khrushchev had immediately been informed of the flight and viewed the timing of the incursion as a personal affront. The way he saw it, the Americans had humiliatingly thumbed their noses at him, violating Soviet airspace even as he stood on U.S. sovereign diplomatic soil, and challenging him to do something about it. Worst of all, he had been powerless to respond. Soviet air defenses had nothing in their arsenal that could hit the U-2. MiG-19 and MiG-21 fighter jets buzzed like angry hornets under the U-2, catapulting themselves as high as possible, but their conventional engines and stubby wings couldn’t generate the necessary lift to reach it. Antiaircraft batteries sent useless barrages that also fell well short. Only the new P-30 radar had been able to track the intruder with a surprising degree of sophistication, as the diplomatic protest the USSR privately filed on July 10, 1956, indicated. For Khrushchev, this latest incursion had come on the heels of Curtis LeMay’s mock attack on Siberia. Only this time, the Americans had not overflown some remote corner of Russia’s empty Arctic wasteland. They had brazenly put a plane right over Red Square, the symbol of Soviet power, and the most heavily defended piece of airspace in the entire Communist bloc. It was a provocation designed to end any chance of rapprochement. “Certain reactionary circles in the United States,” the Soviets protested, in a thinly veiled swipe at LeMay and the Dulles brothers, were trying to sabotage “the improvement of relations” between the two countries. The Soviets openly blamed “renegade” elements in the U.S. Air Force, though, as John Foster Dulles had predicted, they were careful to keep their complaints quiet.