.

We are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War / Solar dyad

Thinking over to himself: it would be enough to perfect the great thermo-nuclear vectors, and then develop civilian society

PN75/20/02*

(PN post-nuclear calendar, where PN0 = Trinity ’45)

Derek came close to discovering the composition of the New Silk Soul. Prospect Cottage, on the edge of the known world, Dungeness, Kent, dover cliff close, Pynchon’s White Visitation, the streak coming up over Dutchlaunch, remember the passage now, somewhere out over North Sea, a cold smear of sun. He looked a little like John Hurt in 1984. Derek died February 19 1994, I was born February 5 1994, – is it possible as a soul departs…and he’s thinking of Rayleigh soul scattering and hospital new debris

“This well-scrubbed day ought to be no worse than any—Will it? Far to the east, down in the pink sky, something has just sparked, very brightly. A new star, nothing less noticeable. He leans on the parapet to watch. The brilliant point has already become a short vertical white line. It must be somewhere out over the North Sea . . . at least that far … icefields below and a cold smear of sun. . . .What is it? Nothing like this ever happens. But Pirate knows it, after all. He has seen it in a film, just in the last fortnight. . . it’s a vapor trail. Already a finger’s width higher now. But not from an airplane. Airplanes are not launched vertically. This is the new, and still Most Secret, German rocket bomb. “Incoming mail.” Did he whisper that, or only think it? He tightens the ragged belt of his robe. Well, the range of these things is supposed to be over 200 miles. You can’t see a vapor trail 200 miles, now, can you. Oh. Oh, yes: around the curve of the Earth, farther east, the sun over there, just risen over in Holland, is striking the rocket’s exhaust, drops and crystals, making them blaze clear across the sea. . . .The white line, abruptly, has stopped its climb. That would be fuel cutoff, end of burning, what’s their word . . . Brennschluss. We don’t have one. Or else it’s classified. The bottom of the line, the original star, has already begun to vanish in red daybreak. But the rocket will be here before Pirate sees the sun rise.The trail, smudged, slightly torn in two or three directions, hangs in the sky. Already the rocket, gone pure ballistic, has risen higher. But invisible now. Oughtn’t he to be doing something . . . get on to the operations room at Stanmore, they must have it on the Channel radars—no: No time, really. Less than five minutes Hague to here (the time it takes to walk down to the teashop on the corner . . . for light from the sun to reach the planet of love … no time at all). Run out in the street? Warn the others?”

In 1980, there came the Film That Never Was, in Dancing Ledge, he wrote:

NEUTRON – There are six published manuscripts of Neutron, which zig-zag their anti-heroes Aeon and Topaz across the horizon of a bleak and twilit post-nuclear landscape. ‘Artist’ and ‘activist’ in their respective former lives, they are caught up in the apocalypse, where the PA systems of Oblivion crackle with the revelations of John the Divine. Their duel is fought among the rusting technology and darkened catacombs of the Fallen civilization, until they reach the pink marble bunker of Him. The reel of time is looped – angels descend with flame-throwers and crazed religious sects prowl through the undergrowth. The Book of Revelations is worked as science fiction. Lee and I pored over every nuance of this film. We cast it with David Bowie and Steven Bcrkoff, set it in the huge junkcd-out power station at Nine Elms and in the wasteland around the Berlin Wall. Christopher Hobbs produced xeroxes of the pink marble halls of the bunker with their Speer lighting – that echo to ‘the muzak of the spheres’ which played even in the cannibal abattoirs, where the vampire orderlies sipped dark blood from crystal goblets. Neutron is the Sleeping Film – the shadow of the activity surrounding the Caravaggio project – a trailer for the End of the World based on the self-fulfilling prophecy of the Apocalypse. A dream treatment of mass-destruction, of the world’s desire to be put out of its misery, the now-established place the unthinkable has in the popular imagination. Neutron sleeps between its covers like a Cruise or Pershing in its silo, and is overhauled every eighteen months. Jon Savage and I have resurrected its rival protagonists, Aeon, Topaz, and Sophie.

How to make a rapprochment with the financiers?

Will the film be made before the event itself?

Now we’ve opened the film up, and given it an ambiguous ending— allowing Aeon to transcend his death, to set out in exemplary self-chosen poverty like a Bruegel pilgrim or Langland’s Conscience, complete with tall staff and wide-brimmed hat.

14 April 1980, Geneva: Guy Ford and I flew to Geneva to meet David Bowie and talk about Neutron. The project hangs on his decision. We show him The Tempest . . . He is interested, but we have to find the money without using his name. During the following months we met, and crept into Berkoff s Hamlet and Cage Aux Folles. He took me to hear ‘Ashes to Ashes’, and in September we saw him in The Elephant Man in New York, but by then the deadline had passed and I put Neutron quietly back on the shelf. Bowie is the tuning-fork of the media humming to perfection. He is a transparency by Avedon, a xerox by Laurie Chamberlain, a voice embalmed in vinyl. He is the mirror of ambivalence and a monarch of the invisible threads of communication – touch fingers and you hear voices. The people in the streets are drawn to him, a Pied Piper who leads the dance. In repose, he is the still silence at the centre of a dust devil. Writing film scripts without a stable income is a rather uphill task. The Tempest finished a moderate success. I embarked on Neutron, Cavavaggio and Bob Up a Down with a variety of young collaborators who wanted to learn film. Time slipped by. The execs in the TV companies who drew their monthly pay cheques had little idea of the reality of films as art (as opposed to ‘art films’), and the involvement you must bring to a project as you tread an economic tightrope. Phones are liable to get cut off; and the cost of printing and binding scripts is a nightmare. Somehow you muddle by.

See Pynchon and Derek are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War / Solar dyad – they’re levitating, with spittoons of shingle, mist and trellis light come up over northsea – sphere emanatous, bi-solaris, cold war end day die-ads – and it’s a little like Laing’s girl who thought she had an atom bomb in her belly, or Liu’s boy born over nuclear plantal Shanxi:

Mother: Baby, can you hear me? Fetus: Where am I? Mother: Oh, good! You can hear me. I’m your mother. Fetus: Mama! Am I really in your belly? I’m floating in water … […] Fetus: I like this place; I want to stay here forever. […] Fetus: Hmmm. Mama, you’ve never been where I am, have you? Mother: I have! Before I was born, I was inside my mother, too. Except I don’t remember what it was like there, and that’s why you can’t remember, either. Baby, is it dark inside mommy? Can you see anything? Fetus: There’s a faint light coming from outside. It’s a reddish-orange glow, like the color of the sky when the sun is just setting behind the mountain at Xitao Village.

What did Derek write about nuclear plants, Sunday 18 January 1990: Is the nuclear industry the rot at the core of democracy, around which shadowy secrets congregate like moths? I told my neighbours and they laughed. What can any of us do? And what information do we have?

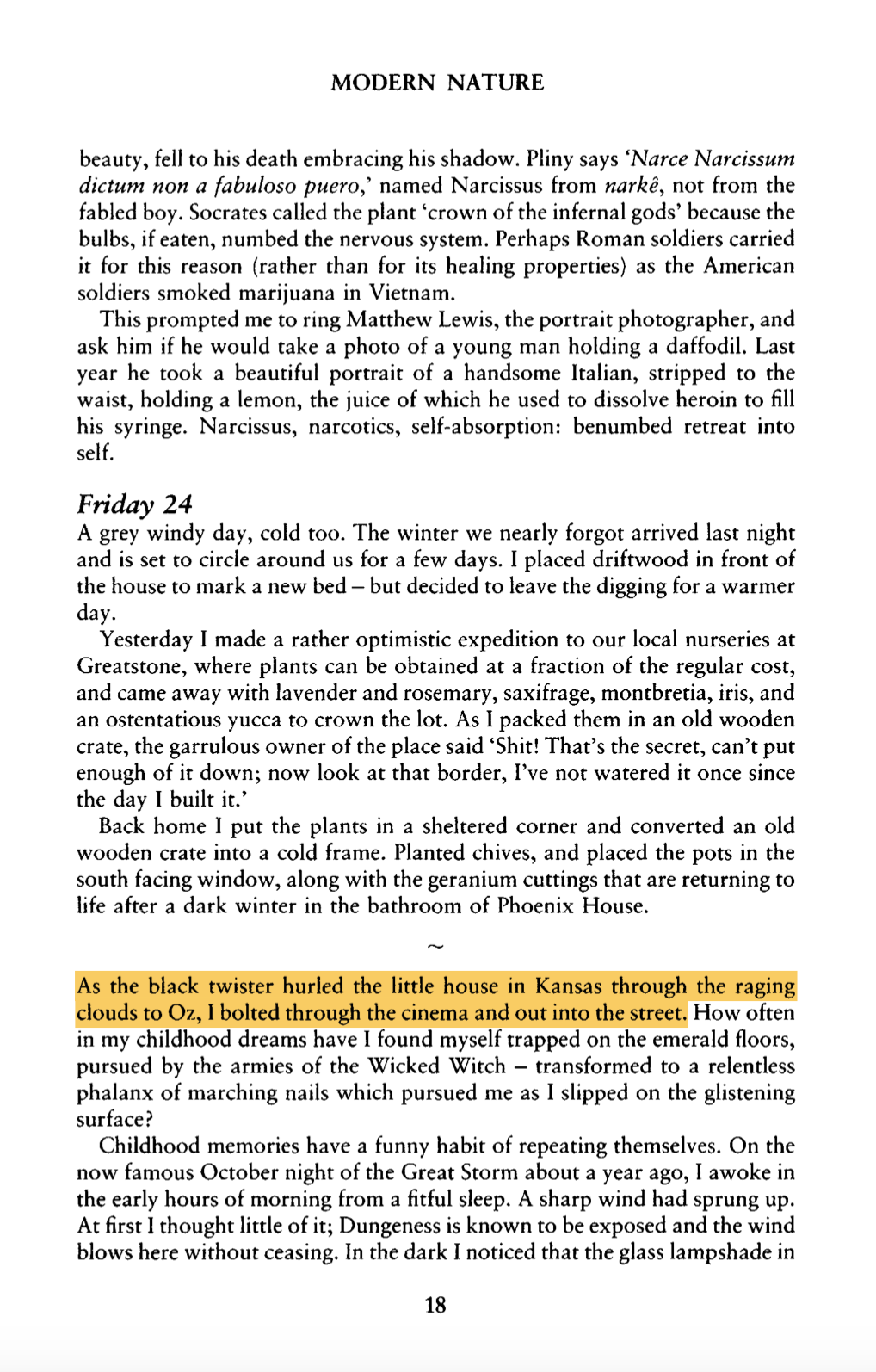

He’s writing on now, in the spectre of dusklight come up over Surreymansion fields – “the Cold War spectre looms in the imaginary of Derek and I think he was coming close to discovering the composition of the New Silk Soul, here is a diary entry from Friday 24 February 1989, 1989 of course was when it all began crumbling, the social catastrophe resonating into an economic, the cataclysm of the mind, co-incidence of light, siniys, goluboys, Putinesques retinizing the whole mausoleum come

collapsed before our eyes, the giant Socialist continent sinking into the sea; and a cosmic one – Chernobyl. Two global eruptions. The first felt closer, more intelligible. People were wrapped up in their day-to-day worlds [umwelts] of what to buy and where to go. What to believe. Which banner to rally round next. Or whether we should now learn to live for ourselves, find our own lives. The idea was unfamiliar for us, we had never lived like that and did not know how to set about it. Each and every one of us was going through this dilemma. But we would have liked to forget Chernobyl, because our minds just wanted to capitulate. It was a cataclysm for our minds. The world of our beliefs and values had been blown apart’ (Alexievich, 2014).

Virilio speaks of it differently, pure war twenty five years later, page 221,

In Pure War you were the first to assert that peace merely extends war by other means. Logistics cannot be stopped. It requires the continual production of increasingly costly and sophisticated armaments at the expense of civil society. History has confirmed your prognostications. Nuclear deterrence achieved its goal without a single bomb being dropped. The war never happened, and yet it was won. The escalation between the two blocks terminated when one ofthe adversaries imploded. The Berlin Wall collapsed, clearing the wayfor the abolition ofall obstacles and the global exchange ofgoods as well as information. Para doxically, the world that resultedfrom that wasn’t more open, but more closed upon itself Instead ofexpanding in space, it contracted in time, and narrowed down. Claustropolis replaced cosmopolis. I’d like to think of these as the pains of childbearing, the contrac tions which prelude delivery; in which case you better have a cab handy to rush the woman to the hospital. Contraction also reminds me ofa telluric contraction, an earthquake. I believe that globaliza tion led to a telluric contraction, to moments that herald the birth of a new world, but a finite world. Paul Valery said: “The time of the finite world is beginning.” We’re living in the time of the finite world, not of a world about to start. We are about to experience together the time of finitude, the magnitude of the finite world’s poverty. This finitude isn’t at its beginning-it all started in the eighteenth century, the finitude of the world, with the industrial revolution and those that followed: transportation, energy trans mission, and others. Nowadays we’re living through the pains and contractions which lead to the delivery of a closed world. This is the closed world that political ecology must confront. The great struggle between tyranny and democracy is going to move from human tyrants-Genghis Khan, or Hitler-to tyranny itself Tyranny came out of progress, which is what has brought about the tyranny of the end. Progress triggered finitude, transportation, the exhaustion of natural resources, speed, real time, etc. Most people think of speed as progress, they believe that speed simply means going faster from one point to another; but they forget that the world is closing in on us and that we’re being asphyxiated by our way of life.

In 1944, AR (Ayn Rand) was hired as a screenwriter by Hal Wallis, the producer of Casablanca. Wallis had just opened his own production studio, and she was the first screenwriter he hired. In late 1945, Wallis suggested that AR write an original screenplay about the development of the atomic bomb:

PN75/21/02

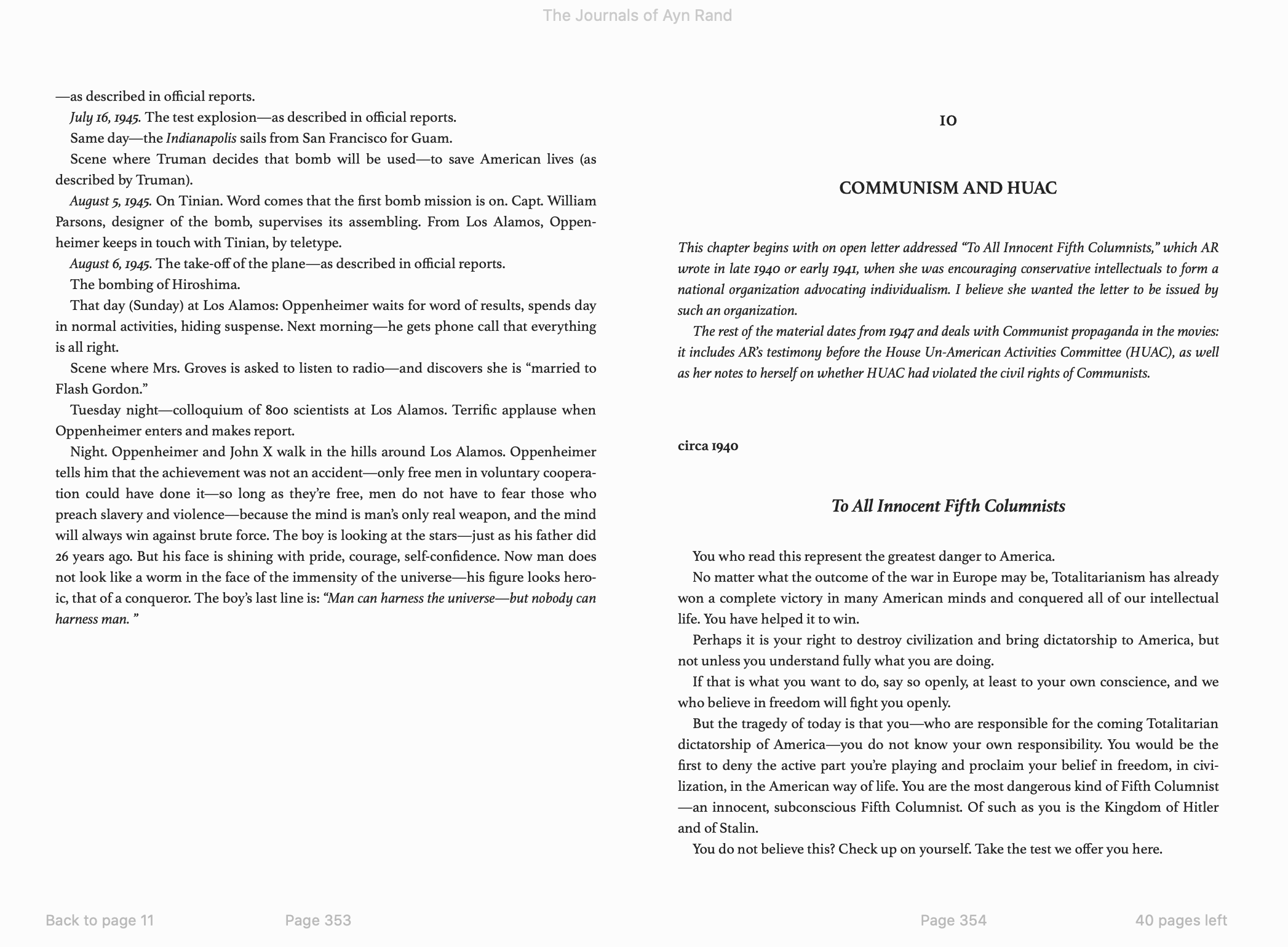

I found one of the six scripts for Neutron, Derek said he visited all the great rusting power stations and factories. ‘Chicago would have been the best location. Now it’s Siberia, one of those decaying complexes, a nuclear base.’ And the film opens with Aeon, Gatsby-esque in a country house not dissimilaring from ones near me here now:

INT. GALLERY. AEON’S COUNTRY HOUSE. DAWN. AEON stands with his back to the camera, silhouetted against the window in the long gallery looking at the garden below. He is lit by the bluish flicker of an empty television screen. He is good looking, in his mid-3Os and immaculately dressed.

4. EXT. GARDEN.AEON’S COUNTRYHOUSE. DAWN Down below two of the REVELLERS have slipped out of their clothes and are making love in the lilypond. In the pale blue light of dawn they seem an Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The beautiful romantic garden with the countryside beyond, a paradise. The sun comes up on a perfect summer morning, sending great streaks of pink and orange across the pale blue sky as the stars fade.

It’s only later scene 11, that something is amiss, some blurry sodium-lit after-light bled from some central event, some happening:

11. EXT. RUINED COURTYARD OF DESERTED FACTORY. EARLY MORNING Aeon’s POV. AEON stares down into a ruined courtyard strewn with industrial debris. It is lit by an eerie sodium light which drains the colour from every surface, thegreyness intensified by the fine ash which has drifted down covering everything in a deathly pall. In the middle of the yard is a bright bonfire around which ragged destitute CHILDREN lie asleep in each other’s arms in a bivouac constructed of old furniture.

22. INT. AEON’S COUNTRYHOUSE. NIGHT

AEON and SOPHIA contemplate suicide. He holds a gun to her forehead and she to his. She then takes it aside and smiles. They embrace.

23. EXT. DERELICT SUPERMARKET. DAY

TOPAZ stands in the shadow of a ruined shop front as a group of OUTRIDERS fan out across the street with flame throwers.

RADIO: [Static] message to all sectors – repeat – allsectors –

I who sit on the throne will come to dwell among you

[Interference}. There will be no more hunger, no more thirst [Static] I will feed you [Static] I will lead you to fountains of living water [Static] I will wipe away all tears [Static] fountains of living water [Static] all tears [Static] I who sit on the throne [Static].

29. INT. VIDEO EDITING SUITE. NIGHT

AEON watches as his face flickers on a dozen screens, and the sound of his drumming fingers becomes the rhythm of a song, which shows the world’s leaders, and marching feet, missiles, tanks, interspersed with dancers who dance at the edge of time to AEON’S immaculate performance.

Then – slight enough, blinking – scene 39

39. EXT. THE BOMB AND THE CITY. DAY

In an intense white light an image of a great metropolis glimmers briefly and turns to ashes.

40. EXT. CITY STREET. DAY/NIGHT

In a storm of ashes PEOPLE run wild, some are looting, the others move from side to side of the street like a tidal wave. AEON: [Voice over] People were running and screaming like some January sale gone mad. Carrying looted clothes, electrical goods and TV sets.

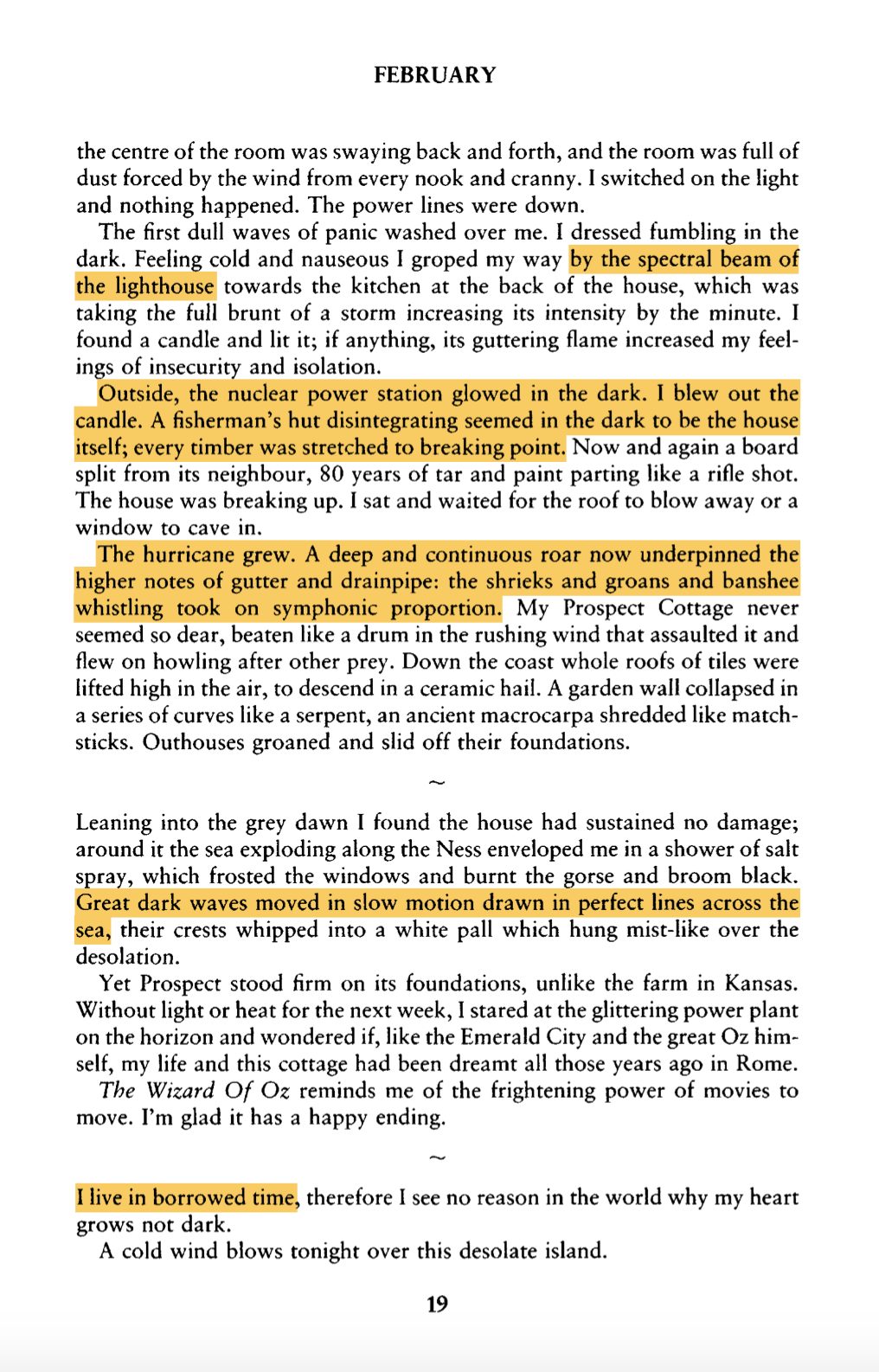

We are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War / Solar dyad. See Derek seemed to be tracing two speeds in the mind, the resonances where time goes askew, future and past, wrote it himself, time is scattered, the past and the future, the future past and present. – siniy and goluboy, the crackle and longer resonance – invective fear saturating on the wind, blink and you’ll miss the wartide, blink and you’ll miss the lesions brokered across the retina – the impossibility of imagining that moment when you can see through your arm, all bone and empty X-ray light, the impossibility of chronology, given over to millisecondal splitting death with your name on it, I’ve seen the barometric pulse that came from Semipalatinsk, not far from the Siberian set of The Film That Never Was, men crouched in observation towers, B52s riding cameras lopped groundward, tensed to the primal scream comelit before it hits you, hurts you, breaks down your marriage 20 years melanomatic later, adrift bars, drowning out – the superposition of resonance sunsets in that moment that wasn’t even, that shaped your skin register, your heartvalves,your greymatter skullballs, then there is the nuclear winter primal ambient cord Basinski-like disintegrationing on 9/11 New York rooftop interminable loss and lust somewhere deep in the neural tap leaking A cold wind blown over tonight on this desolate island.

Over the hills and dales, over mountain and marsh, down the great roads and little lanes, through the villages and small towns, through the great towns and the cities. Everywhere it blows through empty streets and desolate houses, rattling the hedgerows and broken windows, drumming on locked doors. This wind is blowing high in the tower blocks and steeples, down along the river, invading houses and mansions, through the corridors and up the staircases, rustling the faded curtains in bedrooms, over the carpets, up the aisles and down in the crypts, in public places and private, among forgotten secrets, round the armchair, the easy chair, across the kitchen table. So icy is this wind that it rattles the bones in the graves and sends rats shi- vering down the sewers. Fragments of memory eddy past and are lost in the dark. In the gusts yellowing half-forgotten papers whirl old headlines up and over dingy sub- urban houses, past leaders and obituaries, the debris of inaction, into the void. Thought illuminated briefly by lightning. The rainbows are put out, the crocks of gold lie rusting —forgotten as the fallen trees which strew the fieldsand dead meadows. I consider the lives of warriors, how they suddenly left their halls. Bold and noble leaders, I shiver and regret my time. But the wind does not stop for my thoughts. It whips across the flooded gravel pits drumming up waves on their waters that glint hard and metallic in the night, over the shingle, rustling the dead gorse and skeletal bugloss, running in rivulets through the parched grass – while I sit here in the dark holding a candle that throws my divided shadow across the room, and gathers my thoughts to the flame like moths. I have not moved for many hours. Years, a lifetime, eddy past: one, two, three: into the small hours, the clock chimes. The wind is singing now. Eternity, eternity Where will you spend eternity? Heaven or hell, which shall it be, Where will you spend eternity? And then the wind is gone, chasing itself across the shingle to lose itself in the waves which brush past the Ness, throwing up plumes of salt spray which spatter across the windows. Nothing can hide from it. Certainly no man can be wise before he has lived his share of winters in the world.

Pirate and Osbie Feel are leaning on their roof-ledge, a magnificent sunset across and up the winding river, the imperial serpent, crowds of factories, flats, parks, smoky spires and gables, incandescent sky casting downward across the miles of deep streets and roofs cluttering and sinuous river Thames a drastic stain of burnt orange to remind a visitor of his mortal transience here, to seal or empty all the doors and windows in sight to his eyes that look only for a bit of company, a word or two in the street before he goes up to the soap-heavy smell of the rented room and the squares of coral sunset on the floorboards—an antique light, self-absorbed, fuel consumed in the metered winter holocaust, the more distant shapes among the threads or sheets of smoke now perfect ash ruins of themselves, nearer windows, struck a moment by the sun, not reflecting at all but containing the same destroying light, this intense fading in which there is no promise of return, light that rusts the government cars at the curbsides, varnishes the last faces hurrying past the shops in the cold as if a vast siren had finally sounded, light that makes chilled untraveled canals of many streets, and that fills with the starlings of London, converging by millions to hazy stone pedestals, to emptying squares and a great collective sleep. They flow in rings, concentric rings, on the radar screens. The operators call them “angels.”

In some cities the rich live upon the heights, and the poor are found below. In others the rich occupy the shoreline, while the poor must live inland. Now in London, here is a gra-dient of wretchedness? increasing as the river widens to the sea. I am only ask-ing, why? Is it because of the ship-ping? Is it in the pat-terns of land use, especially those relating to the Industrial Age? Is it a case of an-cient tribal tabu, surviving down all the Eng-lish generations? No. The true reason is the Threat From The East, you see. And the South: from the mass of Eu-rope, certainly. The people out here were meant to go down first. We’re expendable: those in the West End, and north of the river are not. Oh, I don’t mean the Threat has this or that specific shape. Political, no. “If the City Paranoiac dreams, it’s not accessible to us. Perhaps the Ci-ty dreamed of another, en-emy city, float-ing across the sea to invade the es-tuary … or of waves of darkness . . . waves of fire. . . . Perhaps of being swallowed again, by the immense, the si-lent Mother Con-tinent? It’s none of my business, city dreams. . . . But what if the Ci-ty were a growing neo-plasm, across the centuries, always changing, to meet exactly the chang-ing shape of its very worst, se-cret fears? The raggedy pawns, the disgraced bish-op and cowardly knight, all we condemned, we irreversibly lost, are left out here, exposed and wait-ing. It was known, don’t deny it—known, Pointsman! that the front in Eu-rope someday must develop like this? move away east, make the rock-ets necessary, and known how, and where, the rockets would fall short. Ask your friend Mexico? look at the densities on his map? east, east, and south of the river too, where all the bugs live, that’s who’s getting it thickest, my friend. p270 Pynchon G-R

We are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War / Solar dyad

PN75/23/02

Why dyads? War is always in Twos. The two cities held in a tensional doom loop – for Berlin, had London, Kashmir, has [ ] | the war is a world of dyads tensely primed to each other’s gesture, a ballroom, a nuclear missile dance, and off-screen, the third partner, waiting in the wings, stirring a three body problem, the love and death triangle of heavy elements.

‘Nothing can alter the fact that the geographical situation of Britain offers to a Continental Power such targets as London and the other great cities. Dispersal of munitions works and airfields cannot alter the facts of geography’. Britain, highly urbanised, highly industrialised and geographically and demographically compact, was much more vulnerable than either the United States or the Soviet Union, with their vast tracts of lands and low population densities. [..] We recognised, or some of us did, before this war that bombing could only be answered by counter bombing. We were right. Berlin and Magdeburg were the answer to London and Coventry. Both derive from Guernica. The answer to an atomic bomb on London is an atomic bomb on another great city. (After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Cold War Britain, 1945 – 68 (Matthew Grant, 2010) See The Effects of the Atomic Bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Report of the British Mission to Japan (https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/4430289)

Amis: The central concept in nuclear-winter theory is synergism. When two bad things happen, a third (and unpredictable) bad thing happens [OPPIE CALLED THE BOMB TRINITY AFTER JOHN DONNE POEM] , exceeding the sum of the individual effects. This is on top of the bad things we know a good deal about, already quite a list. Prompt radiation, superstellar temperatures, electromagnetic pulse, thermal pulse, blast overpressure, fallout, disease, loss of immunity, cold, dark, contamination, inherited deformity, ozone depletion: with what hysterical ferocity, with what farcical disproportion, do nuclear weapons loathe human life. . . . It is possible to imagine nuclear synergisms multiplying into eternity, popping and crackling away, inimical to life even when there is nothing left to be inimical to. The theory of nuclear winter was prompted by studies of dust storms on Mars, and Mars gives us a plausible vision of a postnuclear world. It is vulcanized, oxidized, sterilized. It is the planet of war. Excerpt From: Martin Amis. Einstein’s Monsters, page 17

Likewise the Artificial Intelligent Lifeform and the Human LifeForm began to breathe through each other, ventilate – a bicameral, siamese, hemispheric promise.

Coupling is simplicity itself. It’s at the root of all conflict. You’re right to say that the USSR and the United States are cou pled. When you talk about the Soviet Union, you have to talk about the United States, and vice-versa. Together they form a system. The American military-industrial complex was the model for the Soviet military-industrial complex. The Soviets were fascinated by the Americans. You hear more and more that they’ve now surpassed them: sure, it’s not the quantity that counts, it’s the qual ity. Because strategy is more qualitative than quantitative-in nuclear power, that is, in mass power. The Soviet Union is Ameri ca’s former student, a student which has free reign in matters ofwar economy since in a socialist economy you can invest capital any way you want. This said, the Soviet military-industrial complex, the “stratocracy,” as Castoriadis says, is only an image, a reflection of the American military class. So we can’t understand the evolution of the Soviet Union on the geostrategic and military levels without looking at what’s happening in America. We know that real power in the United States is in the hands of the Pentagon. The American military class passed the buck of the Vietnam failure to the political class, which happened to be Nixon. Watergate was a magic trick which allowed the American military class to come out safe and sound by discrediting politics.

Couplings of light and darkness drive the century underground – the Manichaean, Zoroastrian lens – Cold War Lunatic Inertial Optics – that can only sees axes and dyads of darkness and light

More than half a mile under the earth, in a laboratory set into a band of translucent silver rock salt left behind by the evaporation of an epicontinental northern sea some 250 million years earlier, a young physicist is trying to look into a void. He sits watching a computer screen, close to a large silver cube. The cube’s name is DRIFT and it is a breath-catcher. The young physicist is trying to catch the faint breath of a particle wind sent blowing across space from a constellation called Cygnus, the Swan, many light years distant from Earth. It is a paradox of his work that in order to watch the stars he must descend far from the sun. Sometimes in the darkness you can see more clearly. The young physicist is searching for evidence of the shadowy presence at the heart of the universe: a presence so mysterious that it has thus far engulfed almost all of our attempts either to investigate or to represent it. The name we have given to this presence – which refuses to interact with light, which may not even exist – is ‘dark matter’. ” “Dark matter is fundamental to everything in the universe; it anchors all structures together. Without dark matter, super-clusters, galaxies, planets, humans, fleas and bacilli would not exist. To prove and decipher the existence of dark matter, writes Kent Meyers, would be to approach ‘the revelation of a new order, a new universe, in which even light will be known differently, and darkness as well’.

But like nuclear rods, we may think a trauma is buried, kelavalan, but the mind’s rods are exposure plates not depth-cords.

Deleuze and Guattari propose that, once we reject the notion of a secret as something hidden that might be revealed (or the ‘binary machine’, as we saw above), and try to think of it instead in terms of becomings, we also shift, in more psychoanalytic terms, from ‘hysterical childhood content’ to ‘virile paranoid form’.8 That is to say, analysis can no longer be about exposing a childhood trauma (that is itself related to and structured by the Oedipus complex). It now must reckon with the eternal semiosis, or the unending signifying chain, of the paranoid mind – a mind that, as soon as one claims to have exposed a hidden truth that is the cause for its symptomatic belief in a fantastic conspiracy, absorbs that supposed truth back into the conspiracy. As Deleuze and Guattari put it, the paranoid mind might be seen to operate in one of two ways. ‘On the one hand’, they write, ‘paranoids denounce the international plot of those who steal their secret . . . or they declare that they have the gift of perceiving the secrets of others’. Here the model of the secret as concealment and revelation retains some force. ‘On the other hand’, however, ‘paranoics act by means of, or else suffer from, rays they emit or receive . . . Influence by rays, and doubling by flight or echo, are what now give the secret its infinite form, in which perceptions as well as actions pass into imperceptibility. (Derrida’s Secret, Charles Barbour, 2017)

Excerpts from Martin Amis, Einstein’s Monsters, Bujak and the Strong Force or God’s Dice:

His life went deep into the century. Warrior caste, he fought in Warsaw in 1939. He lost his father and two brothers at Katyn. I first met Bujak one wintry morning in the late spring of 1980—or of PN 35, if you use the postnuclear calendar that he sometimes favored. Michiko’s car had something wrong with it, as usual (a flat, on this occasion), and I was down on the street grappling with the burglar tools and the spare.

Now, in 1985, it is hard for me to believe that a city is anything more or other than the sum of its streets, as I sit here with the Upper West Side blatting at my window and fingering my heart. Sometimes in my dreams of New York danger I stare down over the city—and it looks half made, half wrecked, one half (the base perhaps) of something larger torn in two, frayed, twangy, moist with rain or solder. And you mean to tell me, I say to myself, that this is supposed to be a community? . . . My wife and daughter move around among all this, among the violations, the life-trashers, the innocent murderers. Michiko takes our little girl to the daycare center where she works. Daycare—that’s good. But what about dawn care, dusk care, what about night care? If I just had a force I could enfold them with, oh, if I just had the strong force. . . . Bujak was right. In the city now there are loose components, accelerated particles—something has come loose, something is wriggling, lassooing, spinning toward the edge of its groove.

Bujak’s daughter gave the old man a lot of grief. Her first name was Leokadia. Her second name was trouble. Rural-looking yet glamorous, thirty-three, tall, plump, fierce, and tearful, she was the unstable element in Bujak’s nucleus. She had, I noticed, two voices, one for truth, and one for nonsense, one for lies. Against the brown and shiny surface of her old-style dresses, the convex and the concave were interestingly disposed. Her daughter, little Boguslawa, was the byblow of some chaotic twelve-hour romance.

With Bujak, I was always edging into friendship. I don’t know if I ever really made it. Differences of age aren’t easy. Differences of strength aren’t easy. Friendship isn’t easy. When Bujak’s own holocaust came calling, I was some help to him; I was better than nothing. I went to the court. I went to the cemetery. I took my share of the strong force, what little I could take. . . . Perhaps a dozen times during that summer, before the catastrophe came (it was heading toward him slowly, gathering speed), I sat up late on his back porch when all the women had gone to bed. Bujak stargazed. He talked and drank his tea. “Traveling at the speed of light,” he said one time, “you could cross the whole universe in less than a second. Time and distance would be annihilated, and all futures possible.” No shit? I thought. Or again: “If you could linger on the brink of a singularity, time would be so slow that a night would pass in forty-five seconds, and there would be three American elections in the space of seven days.” Three American elections, I said to myself. Whew, what a boring week. And why is he the dreamer, while I am bound to the low earth? Feeling mean, I often despised the dreaming Bujak, but I entertained late-night warmth for him too, for the accretions of experience (time having worked on his face like a sculptor, awful slow), and I feared him—I feared the energy coiled, seized, and locked in Bujak. Staring up at our little disk of stars (and perhaps there are better residential galaxies than our own: cleaner, safer, more gentrified), I sensed only the false stillness of the black nightmap, its beauty concealing great and routine violence, the fleeing universe, with matter racing apart, exploding to the limits of space and time, all tugs and curves, all hubble and doppler, infinitely and eternally hostile. . . . This evening, as I write, the New York sky is also full of stars—the same stars. There. There is Michiko coming down the street, hand in hand with our little girl. They made it. Home at last. Above them the gods shoot crap with their black dice: threes and fives and ones.The Plough has just rolled a four and a two. But who throws the six, the six, the six?

All peculiarly modern ills, all fresh distortions and distempers, Bujak attributed to one thing: Einsteinian knowledge, knowledge of the strong force. It was his central paradox that the greatest—the purest, the most magical— genius of our time should have introduced the earth to such squalor, profanity, and panic.

Last summer we took her to England. The pound was weak and the dollar was strong—the bold, the swaggering dollar, plunderer of Europe. We took her to London, London West, carnival country with its sons of thunder.” | nuclearity

We stood and watched each other through the heavy rain.

Later, I was some help to him, I think, when it was my turn to tangle with the strong force. For some reason Michiko could bear none of this; the very next day she bowed out on me and went straight back to America. Why? She had and still has ten times my strength. Perhaps that was it. Perhaps she was too strong to bend to the strong force. Anyway, I make no special claims here.

… In the evenings Bujak would come and sit in my kitchen, filling the room. He wanted proximity, he wanted to be elsewhere. He didn’t talk. The small corridor hummed with strange emanations, pulsings, fallout. It was often hard to move, hard to breathe. “What do strong men feel when their strength is leaving them? Do they listen to the past or do they just hear things—voices, music, the cauldron bubble of distant hooves?

At Kennedy what do I find but Michiko staring me in the face and telling me she’s pregnant. There and then I went down on my lousy knees and begged her not to have it. But she had it all right—two months early. Jesus, a new horror story by Edgar Allan Poe: The Premature Baby. Under the jar, under the lamp, jaundice, pneumonia —she even had a heart attack. So did I, when they told me. She made it in the end, though. She’s great now, in 1985. You should see her. It is the love bomb and its fallout that energize you in the end. You couldn’t begin to do it without the love. . . . That’s them on the stairs, I think. Yes, in they come, changing everything. Here is Roza, and here is Michiko, and here am I.

There was lunch on the sun-absorbing pine table: beer, cider, noise, and the sun’s phototherapy. The violence with which the fiftyish redhead scolded Bujak about his appearance made it plain to me that there was a romantic attachment. Even then, with the old guy nearer seventy than sixty, I thought with awe of Bujak in the sack. Bujak in the bag! Incredibly, his happiness was intact—unimpaired, entire. How come? Because, I think, his generosity extended not just to the earth but to the universe—or simply that he loved all matter, its spin and charm, redshifts and blueshifts, its underthings. The happiness was there. It was the strength that had gone from him forever. Over lunch he said that, a week or two ago, he had seen a man hitting a woman on the street. He shouted at them and broke it up.

And now that Bujak has laid down his arms, I don’t know why, but I am minutely stronger. I don’t know why—I can’t tell you why.

He once said to me: “There must be more matter in the universe than we think. Else the distances are horrible. I’m nauseated.” Einsteinian to the end, Bujak was an Oscillationist, claiming that the Big Bang will forever alternate with the Big Crunch, that the universe would expand only until unanimous gravity called it back to start again. At that moment, with the cosmos turning on its hinges, light would begin to travel backward, received by the stars and pouring from our human eyes. If, and I can’t believe it, time would also be reversed, as Bujak maintained (will we move backward too? Will we have any say in things?), then this moment as I shake his hand shall be the start of my story, his story, our story, and we will slip downtime of each other’s lives, to meet four years from now, when, out of the fiercest grief, Bujak’s lost women will reappear, born in blood (and we will have our conversations, too, backing away from the same conclusion), until Boguslawa folds into Leokadia, and Leokadia folds into Monika, and Monika is there to be enfolded by Bujak until it is her turn to recede, kissing her fingertips, backing away over the fields to the distant girl with no time for him (will that be any easier to bear than the other way around?), and then big Bujak shrinks, becoming the weakest thing there is, helpless, indefensible, naked, weeping, blind and tiny, and folding into Roza.

“Every morning, six days a week, I leave the house and drive a mile to the flat where I work. For seven or eight hours I am alone. Each time I hear a sudden whining in the air, or hear one of the more atrocious impacts of city life, or play host to a certain kind of unwelcome thought, I can’t help wondering how it might be. Suppose I survive. Suppose my eyes aren’t pouring down my face, suppose I am untouched by the hurricane of secondary missiles that all mortar, metal, and glass has abruptly become: suppose all this. I shall be obliged (and it’s the last thing I’ll feel like doing) to retrace that long mile home, through the firestorm, the remains of the thousand-mile-an-hour winds, the warped atoms, the groveling dead. Then—God willing, if I still have the strength, and, of course, if they are still alive—I must find my wife and children and I must kill them.”

Excerpts from Peter Sloterdijk, Bubbles and Pure War, Paul Virilio

Spheres are constantly disquieted by their inevitable instability: like happiness and glass, they bear the risks native to everything that shatters easily. They would not be constructs of vital geometry if they could not implode; even less so, however, if they were not also capable of expanding into richer structures under the pressure of group growth. Where implosion occurs, the shared space as such is cancelled out. What Heidegger called being-toward-death means not so much the individual’s long march into a final solitude anticipated with panic-stricken resolve; it is rather the circumstance that all individuals will one day leave the space in which they were allied with others in a current, strong relationship. That is why death ultimately concerns the survivors more than the deceased. Human death thus always has two faces: one that leaves behind a rigid body and one that shows sphere residues – those that are sublated into higher spaces and re-animated and those that, as the waste products of things, fallen out of former spaces of animation, are left lying there. In structural terms, what we call the end of the world is the death of a sphere. This small-scale emergency is the separation of the lovers, the empty apartment, the torn-up photograph; its comprehensive form manifests itself as the death of a culture, the burnt-out city, the extinct language. Human and historical experience at least shows that spheres can continue to exist even beyond mortal separation, and that things lost can remain present in memories – as a memorial, a spectre, a mission or as knowledge. It is only because of this that not every separation of lovers need become the end of the world, and not every change undergone by language a culture’s demise.

The fact that the internally differentiated bubble of those in intimate coexistence can initially seem to be resolutely closed and secure in itself is due to the tendency of the communicating poles to be consumed fully in their care for the other half. […] Unscathed sphere carry their destruction within themselves: this too is taught with merciless stringency by the Jewish paradise account. There is nothing to impair the perfection of the first pneumatic bubble until the disturbance of a sphere leads to the primal catastrophe. The distractable Adam falls prey to a second inspiration through the secondary voices of the serpent and the woman; as a result he discovers what theologians call his freedom. Initially, however, this consists only in a certain willing openness to seduction by outside elements. The phenomenon of freedom subsequently takes on its full, unnerving magnitude by installing radicalised independence of will and the desire for other things than those prescribed. From the very first whim of individual freedom, however, humans lost the ability to stay in their place within the purely sounding biunity of the God-self space, devoid of all secondary voices. The ‘expulsion from paradise’ is a mythical title for the spherological primal catastrophe – in psychological terminology it would be paraphrased as a general weaning trauma. Only an event of this kind – the withdrawal of the first completer – could give rise to what would later be termed the ‘psyche’ : the semblance of a soul that, almost like a private spark or an isolated vital principle, inhabits a single desirous body. The mythical process outlines the inevitable corruption of the original interior-forming biunity through the emergence of a third, a fourth and a fifth. The biune world had known neither number nor resistance, for even the mere awareness that there were other things, countable and third options, would have corrupted the initial homeostasis. (page 50-51)

In the dyad, the united two even have the power to deny their twoness in unison; in their breathed retreat they form an alliance against number and interstices. We are what we are, without separation and joints: this space of happiness, this vibration, this animated echo chamber. We live, as intertwined beings in the land of We. But this measureless, numberless happiness with closed eyes cannot ever last anywhere; in post-paradise times – and does the count not always start ‘after paradise lost’ ? – the sublime biune bubble is damned to burst. The modalities of bursting set the conditions for cultural histories. Transitional objects, new themes, secondary themes, multiplicities and new media step between the two partners; the symbiotic space, once intimate and filled with a single motif, opens up into a multiple neutrality, where freedom is only granted along with foreignness, indifference and plurality. It is torn open by non-symbioticc urgencies; for the new is always born as something that disturbs earlier symbioses. It intervenes in the individual interior as an alarm and a compulsion. Now the adult cosmos becomes clear as the epitome of work, struggle, diversion and coercion. What was God becomes a lonely, transcendent pole. He survives in the only way he can: as a distant, delusional address for scattered quests for salvation. What was Adam’s symbiotically hollow interior now opens itself up to more and less spiritless occupants known as worries, entertainments or discourses; these fill out the space that, in the intimate state of coexistence, would have wanted to remain for free for the one, the initial breath partner. The adult has now understood that he has no right to happiness; at most, a call to remember that other state. Who would be allowed to follow it? The utmost that a consciousness filled with worry and violence can allow itself in the way of symbolic nurturance are back-ward looking, yet also future-summoning phantasms of the reinstated dyad.

The spherological drama of development – the emergence into history – begins at the moment when individuals step out into the multipolar worlds of adults as poles of a biunity field. They inevitably suffer a form of mental resettlement shock when the first bubble bursts, an existential uprooting: they come out of their infantile state [BUT AMIS DESCRIBED THE BOMB AS INFANTILIST, LITTLE BOY DROPPED OVER HIROSHIMA] by ceasing to live completely under he shadow of the united other and thus starting to become inhabitants of an expanded psycho-sociosphere. For them, this is where the birth of the outside takes place: upon emerging into the open, humans discover what they initially think they can never become part of their own inner coanimated realm. There are, as humans learn fascinatedly and painfully, more dead and outer things between heaven and earth than any worldling can dream of appropriating.

Yami Lester was 10 years old when the Totem 1 test was conducted on 15 October 1953 near his home at Wallatinna. The winds carried dust into his eyes and four years later he lost all sight:

It was in the morning, around seven. I was just playing with the other kids. That’s when the bomb went off. I remember the noise. It was a strange noise, not loud, not like anything I’d ever heard before. The earth shook at the same time; we could feel the whole place move. We didn’t see anything, though. Us kids had no idea what it was. I just kept playing. It wasn’t long after that a black smoke came through. A strange black smoke, it was shiny and oily. A few hours later we all got crook, every one of us. We were all vomiting; we had diarrhoea, skin rashes and sore eyes. I had really sore eyes. They were so sore I couldn’t open them for two or three weeks. Some of the older people, they died. They were too weak to survive all of the sickness. The closest clinic was 400 miles away

It took years—and the Royal Commission—before the Australian Government would begin to address the full impact of British nuclear testing on the Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara peoples, whose lands in South Australia were taken for the Maralinga test site.31 Little thought was given to the reality that the deserts and oceans of the southern hemisphere were not open, empty places, but home to Indigenous peoples… the weapons prototypes, dubbed ‘Blue Danube’ and ‘Red Beard’

When one attempts to develop weapons of communication the possibility of a new type of accident arises. In the fifties, when Einstein met the Abbe Pierre20-yes, they met, the Abbe Pierre told me himself-what did Einstein say to him? He told him that there are three kinds of bomb. The first is the atomic bomb, and we know what that is: deterrence begins right there; the second is the infor mation explosion; he didn’t say computer, since the word didn’t yet exist, but I can call it an explosion in computer technology. And the third will be the demographic explosion, which is to say the expo nential population boom. Now, if we take Einstein’s term rather than the Pentagon’s, waging an information war means the setting off of the technology bomb. In other words, information doesn’t merely transmit or conmunicate the news, facts, but rather deals with interactivity and organization. I remind you that the atom bomb is about radioactivity, or more precisely, organizing it so that there’s an explosion, fusion, fission, or pollution. Now, the technology bomb isn’t just used for information technology, it also involves interactivity to a degree one can’t even imagine; feedbacks whose consequences one can’t even fathom since we’ve never seen that before. Like the atom bomb, in fact. It is another kind of accident than nuclear accidents such as the melt-downs at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. It’s an information accident. Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds…Yes, exactly. No longer an accident involving an explosion or radioactivity, but interactivity among people. And that’s unknown territory. It’s some kind of information panic…Yes, tangentially. My next book will deal with anticipation. It will be the first of its kind, even. For once, I ‘m going to try to forecast this integral accident. The word “integral” is very important. Have there already been events thatforeshadow this integral accident? Only one: the stock market crash. It isn’t enough, but it is a fore taste in the sense that it simultaneously happened everywhere. It is no longer localized as a specific accident, it is not located where the “Titanic” sank, or Chernobyl leaked, but it is everywhere. In this regard, it’s much like the bomb that goes off. Boom. But what is it that booms? We don’t even know. It’s a phenomenon . . . A phenomenon of instant saturation, or a kind of vitrification of the world? We have to work hard to know what it is because is has never happened before. The atomic bomb went beyond the competence of the military staffs and that’s why they came up with deterrence. You could reduce or increase the bomb in size, but it went beyond them-deterrence is the fruit ofnuclear power. Once the information bomb is recognized as such, as a power that overwhelms military staffs, it may well be that a number of states, America, but certainly Japan and Europe as well, will impose a form of information deterrence, a societal deterrence. No longer nuclear deterrence, preventing the use ofsuch weapons, but deterring the masses faced with flashpoint situations. I don’t think it will take long before the information bomb is recognized as such. The delirium surrounding the Internet is rather instructive in this respect

Modernity is characterised by the technical production of its immunities and the increasing removal of its safety structures from the traditional theological and cosmological narratives. Industrial scale-civilisation, the welfare state, the world market and the media sphere: all these large-scale projects aim, in a shell-less time, for an imitation of the now impossible, imaginary spheric security. Now networks and insurance policies are meant to replace the celestial domes; telecommunication has to reenact the all-encompassing. The body of humanity seeks to create a new immune constitution in an electronic medial skin, an iron missile dome. Because the old all-encompassing and containing structure, the heavenly continens firmament, is irretrievably lost, that which is no longer encompassed and no longer contained, the former content, must now create its own satisfaction on artificial continents under artificial skies and domes. Birthing the great thermo-political paradox: that to achieve its creation – whole populations, at the centre as well as the margins, must be evacuated from their old casing of temperature regional illusion and exposed to the frosts of freedom. To free up ground for the artificial surrogate sphere, the leftovers of faith in inner worlds and the fiction of security are destroyed in all old countries in the name of a thoroughgoing market enlightenment that promises a better life, yet initially lowers the immune standards of the proletariats and marginal peoples to a devastating degree. Dumfounded masses soon find themselves in the open, without ever receiving a proper explanation of their evacuation’s purpose. Disappointed, cold and abandoned, they wrap themselves in surrogates of older conceptions of the world, as long as these still seem to hold a trace of their warmth of old human illusions of encompassedness.

Who gives us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sidewards, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Aren’t we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Tolstoy asserted the primacy of the moral and religious sense over the claims of reason, and like them he advocates the simple yet profound wisdom of the Russian peasantry against the godless absolutism of the West. And he thought how it squared up with his own personal globe, his mother’s apoliticalness, William Davies on nervous states, the resurgence of religious moral convictions in Russia, Turkey, Iran, India – the lie the secular state, and how the bomb interpellated with the gods.

The Canary

Stock markets… STOCK EXCHANGE screens, and, then, only from a particular angle: that ofthe curved distorting mirror ofthe round ness of the terrestrial globe – in other words, the continuum of an accelerating ‘globalization of affects’ by traders operating in a market that’s now, once and for all, interconnected through PROGRAM TRADING, through the synchro nization of an interactivity that makes a whole new kind of insider trading possible (See Virilio – The Great Accelerator)

Re: the Starlink satellite programme…

This, I think, explains the importance of the term ANAMORPHOSIS in relation to tempo rality and to the sudden temporal compression of financial data before the curvature, the distorting mirror, ofthe continuum ofan economic history that resides today in the astronomical TEMPO of an instantaneity and an interactivity that once and for all spurn the old laws of a competitive market where the felony of insider trading, perpetrated by cheats, was still committed within the common historical TEMPO of the chro nology of days, hours and seconds – not within the NANOCHRONOLOGY of nanoseconds, picoseconds or femtoseconds of an ‘informa tion bomb’ that is currently in the process of exploding before our very eyes.

a ‘crash of confidence’, as devastating as the choc des civilisations, the clash of civilizations, with the ATHEISM of the free thinker suddenly turning into an atheism of free trade, in the age of banks that are too big to fail, but, especially, too swift to be honest!

After the End of History was forecast last century, the End of Time is now being fore cast, certainly in theoretical physics, but also in relation to political economics.

In the end, what is most revealing in this gen eral disarray is perhaps what Benoit Mandelbrot claimed in 2004, when he said that the con ventional mathematical models employed by the stock market ‘are not only wrong; they are dangerously wrong.’ 1

Faced with the repetition of a crash that will soon be systemic, we have no choice but to ask ourselves about the powerlessness ofsavvy econo mists to interpret the alarm bells that have been ringing steadily for a quarter of a century and, in particular, since the 1987 crash.

Trying to describe the catastrophic swings observed over such a long period throughout the Single Market, Mandelbrot introduced multifrac tal time and thus ushered the history of finance into a dynamic world, where stock market trad ing time no longer has anything in common with physical time, since, in this new model, ‘trading time speeds up the clock in periods of high vola tility, and slows it down in periods of stability’, 1 the space of fractal geometry combining here with the ‘multifractal’ chronometry ofthe fourth dimension.

With our professor emeritus, then, it is no longer just ‘critical space’ that is heralded, but the effraction of H istory, the ‘critical spacetime’ of times to come!

With Benoit Mandelbrot, then, property bubbles suddenly turn tnto FINANCIAL MANDELBUBBLES, not just within the expanse of real estate, but also within time, the long durations of the ‘world economy’ so dear to Fernand Braude!.

Strangely, we note yet again that the ‘loop’ and the ‘sphere’ shoot to the fore, as though the circular time of days gone by was reasserting its rights over the linear time of a Progress once continuous . . .

After Karl Popper’s famous ‘feedback loops’, Carlo Rovelli, as we’ve just seen, now introduces his ‘loop quantum gravity’.

Circular time yesterday, linear time ofprogress right now, and tomorrow, or soon after no doubt, thanks to Mandelbrot, globalitarian time . . . Here TIME – from the Latin tempus, which referred to a ‘fraction of duration’ as distinct from aevum, which was used of continuity and of an ‘era’ – really is the ACCIDENT TO END ALL ACCIDENTS. This is because ‘multifrac tal’ effraction of the durations involved in stock exchange operations tallies with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, only to be applied to the modellers, the financial planners in a finance industry that has gone algorithmic, the famous credit crunch of the market here signal-ling the end of an era, the BIG CRUNCH of turbocapitalism

The city was the means of mapping out a political space that existed in a given political duration. Now speed-ubiquity, instan taneousness-dissolves the city, or rather displaces it. And displaces it, I would say, in time. We have entered another kind of capital, which corresponds to another kind of population. We no longer populate stationariness (cities as great parking lots for populations), we populate the time spent changing place, travel-time. What we are noticing on the level of urban planning has already been noticed on the level of specific neighborhoods, of individuals, even of being at the mercy of phone calls. There is a kind of destruction caused by saturating immediacy, which is linked to speed. So it seems to me that the danger of nuclear power should be seen less in the perspective ofthe destruction ofpopulations than ofthe destruction of societal temporality.

In each lived period, there are overlappings of different ages. We know that at this very moment we are living in both the Neolithic Age (in the depths of Amazonia or with the Australian aborigines) and the Nuclear Age. What I’ve just said doesn’t dismiss all that with a wave of the hand. There are very differentiated coexistences in this world between “primitive” ways of life, “classical” ways of life, and finally “futuristic” ways of life. I’m not trying to deny that all this coexists.

Ancient societies were built by distributing territory. Whether on the family scale, the group scale, the tribal scale, or the national scale, memory was the earth; inheritance was the earth. The foundation ofpolitics was the inscription oflaws, not only on tables, but in the formation ofa region, nation or city. And I believe this is what is now challenged, contradicted by technology. None of the so-called great politicians today are able to approach the kind of modernity we’ve tried to talk about here. None. All of them have arguments, a “sales pitch” that dates from the nineteenth century. Their problem is still territorialized inscription, in other words the negation of the technical fact. Now, technology-Gilles Deleuze said it-is deterritorialization.

In each lived period, there are overlappings of different ages. We know that at this very moment we are living in both the Neolithic Age (in the depths of Amazonia or with the Australian aborigines) and the Nuclear Age. What I’ve just said doesn’t dismiss all that with a wave of the hand. There are very differentiated coexistences in this world between “primitive” ways of life, “classical” ways of life, and finally “futuristic” ways of life. I’m not trying to deny that all this coexists.

Ancient societies were built by distributing territory. Whether on the family scale, the group scale, the tribal scale, or the national scale, memory was the earth; inheritance was the earth. The foundation ofpolitics was the inscription oflaws, not only on tables, but in the formation ofa region, nation or city. And I believe this is what is now challenged, contradicted by technology. None of the so-called great politicians today are able to approach the kind of modernity we’ve tried to talk about here. None. All of them have arguments, a “sales pitch” that dates from the nineteenth century. Their problem is still territorialized inscription, in other words the negation of the technical fact. Now, technology-Gilles Deleuze said it-is deterritorialization.

The Church

An alternative that would preserve the acquisitive spirit needed for the flourishing of commercialized societies but would keep that spirit in check was to internalize certain forms of acceptable behavior through religion. This is why Protestantism, in Weber’s reading of it, not only was corre- lated with capitalist success but was indispensable for maintaining the otherwise incomprehensible ef orts of capitalists (their working and ac- quiring wealth without consuming it), the decorum of the upper classes, and the acceptance of unequal outcomes by the masses.5 It eschewed os- tentation and the crude behavior that characterized earlier elites. It was aus- tere: it limited the consumption of the elites and imposed bounds on how much wealth was to be displayed. It internalized the sumptuary laws of the past.6 As John Maynard Keynes observed in The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), nineteenth-century capitalism in Britain ensured suf- ficient popular acceptance of the landlord-capitalist-worker hierarchy that the society did not explode in a revolution of the kind that engulfed, one after another, feudal societies in France, China, Russia, the Habsburg Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.7 As long as capitalists used most of their surplus income to invest rather than to consume, the social contract held.8 The internalization of desirable behavior, that behavior which, in John Rawls’s words, reaffirms in its daily actions the main beliefs of a society, was possible thanks to the constraints of religion and the tacit social con- tract. It is not clear if societies so dedicated to the acquisition of wealth, by practically any means, would not explode into chaos were it not for these constraints.

Our actions are no longer “monitored” by the people among whom we live. Adam Smith’s baker’s immoral business actions would have been ob- served by his neighbors. But the immoral actions of people who work in As the internal mechanisms of constraint have atrophied or died or do not work in a globalized setting, they have been replaced by external con- straints, in the form of rules and laws. I do not mean that laws did not exist before. But while internalized constraints on behavior mattered, both laws and self-imposed limits af ected people’s behavior. The present situa- tion is characterized by the disappearance of the latter. In cases where we cannot expect the rich to behave ethically or with sufficient discretion so as not to inflame the passions in those who have less, reinforcement of laws is obviously a good thing.13 In a 2017 lecture, the political historian Pierre Rosenvallon proposed that countries should introduce a modernized ver- sion of sumptuary laws that would either heavily tax or ban certain types of behavior and consumption. The problem is that instead of two hand- rails to help keep the actions of the rich (or anyone, for that matter) on the right path, we now have only one—laws. Morality, having been gutted out internally, has become fully externalized. It has been outsourced from our- selves to society at large.

The conflict between what is legal and what is ethical is nicely illus- trated in a story told by Cicero, and recently retold by Nassim Taleb in Skin in the Game (2018). It concerns Diogenes of Babylon and his pupil Antipater of Tarsus, who disagreed on the following matter: Should the merchant who is bringing grain to Rhodes at a t ime of scarcity and high prices reveal that another ship from Alexandria, also carrying grain, is just about to arrive in Rhodes? From a purely legal point of view, de- fended by Diogenes, it is fully acceptable not to reveal private information— moreover, information that no one could prove the person possessed. But from an ethical point of view, defended by Antipater, it is not. There is, I think, little doubt that the former position would be taken by everyone in today’s business world. Even if they might verbally claim that they would follow Antipater, they would in fact behave like Diogenes. And behavior is all that counts, not what we say about how we would have behaved. There is no internal moral rule, as we have amply seen, that would check the be- havior of top banks and hedge funds, or of companies like Apple, Amazon, and Starbucks, when it comes to tax evasion or tax avoidance; or that of the rich, who hide their wealth from tax authorities, in part legally and in part illegally, in the Caribbean or the Channel Islands. Their objective is to play the game as close to the rules as possible, and if the rules need to be bent or ignored, to try to avoid being caught. And if caught, to try, by using a phalanx of lawyers, to find the most recondite and specious expla- nations for this behavior. And if that fails, then to settle.

In the 1950s, Churchill said, “In ancient warfare, the episodes were more important than the tendencies; in modern warfare, the tendencies are more important than the episodes.” In other words, we are confronted no longer with episodes-the Vietnam War, the Polish affair, the Egyptian-Israeli conflict, etc.-but with tendencies, a statistical vision of the world in which we are inscribed by technology, by the movement ofscience and technology. And it’s not easy to grasp statistical perspectives. Knowing that the Russians crossed the Oder and throwing it back in their faces is very clear. But a ten dency-how do you recognize a tendency?

Now, for the death of the species, there are no priests. The only mediation is by the military, and it’s obvious that the military man is a false priest because the question of death doesn’t interest him. He’s an executioner, not a priest. A new inquisitor. And as he is the inquisitor of all thought-not only within civilian society, but within science itself-war is now infiltrating the social sciences.

In 1829, Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) published a review of James Mill’s Essays on Government (March 1829 Edinburgh Review) in which he envisioned a London where, “in two or three hundred years, a few lean and half-naked fishermen … may wash their nets amidst the relics of her gigantic docks”; a decade later, even more resonantly, he published a review of Leopold Von Ranke’s The Ecclesiastical and Political History of the Popes During the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (October 1840 Edinburgh Review) which closed with a warning to his fellow Whigs that monuments of the superseded past, like the Roman Catholic Church, had endured for ages and were unlikely to vanish overnight; and that emblems of rational progress in the world, like the various Protestant churches, might prove evanescent. Indeed, he concluded, the Catholic Church “may still exist in undiminished vigour when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul’s”. This complex image of relative decline, combined with the representation of a New Zealander (generally conceived of as Maori) brooding over dead London, is significant in its own right, as New Zealand was often described as the home of a successor to the British Empire. Macaulay’s focus on the tourist of the future, the representative of a new empire and a new order, seem to have hit a nerve in an England whose more classically educated citizens were highly conscious of the fate of Rome; the British Empire, just now entering its planetary stage, was in this perspective a clear successor to that paradigm city and empire, and Macaulay’s New Zealander tag became an exceedingly usable metaphor for the fragility of imperial sway, for the apprehension that the colonized would eventually become the colonizer, and for the insecurity of the commercial enterprises necessary for the British Empire to flourish; almost thirty years of incessant use of the trope preceded Gustave Doré‘s famous frontispiece to London: A Pilgrimage (1872) by Blanchard Jerrold (1826-1884). In Doré’s engraving, the New Zealander gazes across the stagnant Thames – a total lack of shipping signifying the death of commerce – at the Babylonic/Roman ruins of the great city. This rendering fixed Macaulay’s image for good, and clearly inspired William Delisle Hay‘s The Doom of the Great City, Being the Narrative of a Survivor, written A.D. 1942 (1880 chap), whose New Zealander protagonist is direly smug about London’s destruction (this may be the first prose fiction to combine a description of London’s violent destruction, as opposed to the more usual inevitable decline on the model of Rome, with a Last Man walk through the ruins); and early readers of Joseph Conrad‘s The Heart of Darkness (February-April 1899 Blackwood’s Magazine; in Youth: A Narrative; and Two Other Stories, coll 1902; 1925) would almost certainly have noted the implications of its crepuscular Thames setting. The image of the New Zealander contemplating the ruins soon became significant for British sf: the trope of contemplation, where past and future are held in one gaze, is a central component in the Ruins and Futurity topos, and is central to a late-nineteenth-century form, the Scientific Romance; a little later, the powerful Hitler Wins novel, Loss of Eden: A Cautionary Tale (1940; vt If Hitler Comes: A Cautionary Tale 1941) by Douglas Brown and Christopher Serpell, begins with a scene that specifically dramatizes the image. It has also been mutedly significant for sf in general, though American sf writers tend to locate the trope in a Dying Earth venue; it has frequently been referenced by visual artists. A twenty-first-century example is the cover art for China Miéville‘s The Tain (2002 chap) by Les Edwards working as Edward Miller. The similarly iconic imagery, within a year or so of its erection in 1886, of the Statue of Liberty mired in the stagnant Hudson with ruined New York visible in the background – see for example J A Mitchell‘s cover and illustrations for his novel The Last American (1889 chap; exp 1902) – demonstrates the power of the Macaulay/Doré version of the old nightmare of the transience of empire. Archaeological fiction in general – in which ruins of our contemporary world, having survived into the future, are bemusedly examined – often echoes the Macaulay/Doré image; one example out of many is Gene Wolfe‘s Seven American Nights (in Orbit 20, anth 1978, ed Damon Knight; 1989 chap dos), where the visitor to the Ruined Earth of America is not only contemplative, but duly and earnestly sketches what he gazes upon, as did the New Zealander before him. For it is not enough that ruins merely be contemplated: they need to be recorded, so that the lessons of Time can sink in (see again Ruins and Futurity). (Source: http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/new_zealander)

The Structural Paradox of the New Silk Road | The Structural Paradox of the New Silk Soul | love is a nuclear paradox*, like Amis says:

Bujak’s daughter gave the old man a lot of grief. Her first name was Leokadia. Her second name was trouble. Rural-looking yet glamorous, thirty-three, tall, plump, fierce, and tearful, she was the unstable element in Bujak’s nucleus. She had, I noticed, two voices, one for truth, and one for nonsense, one for lies. Against the brown and shiny surface of her old-style dresses, the convex and the concave were interestingly disposed. Her daughter, little Boguslawa, was the byblow of some chaotic twelve-hour romance.

She’s great now, in 1985. You should see her. It is the love bomb and its fallout that energize you in the end. You couldn’t begin to do it without the love

Stood shard-top, staring down, London blatting, and it looks half made, half wrecked, one half (the base perhaps) of something larger torn in two, frayed, tangy, moist with rain or solder. In nuclear strategy, there is the stability–instability paradox, how the probability of the Great War is staved while the minor ones increase. Love is a nuclear paradox* fought losing, touch entropy.

an international relations theory regarding the effect of nuclear weapons and mutually assured destruction. It states that when two countries each have nuclear weapons, the probability of a direct war between them greatly decreases, but the probability of minor or indirect conflicts between them increases. This occurs because rational actors want to avoid nuclear wars, and thus they neither start major conflicts nor allow minor conflicts to escalate into major conflicts—thus making it safe to engage in minor conflicts. For instance, during the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union never engaged each other in warfare, but fought proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, Angola, the Middle East, Nicaragua and Afghanistan and spent substantial amounts of money and manpower on gaining relative influence over the third world. A study published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution in 2009 quantitatively evaluated the nuclear peace hypothesis, and found support for the existence of the stability–instability paradox. The study determined that while nuclear weapons promote strategic stability, and prevent large scale wars, they simultaneously allow for more lower intensity conflicts. When a nuclear monopoly exists between two states, and their opponent does not, there is a greater chance of war. In contrast, when there is mutual nuclear weapon ownership with both states possessing nuclear weapons, the odds of war drop precipitously. This effect can be seen in the India–Pakistan relationship and to some degree in Russia–NATO relations. The stability–instability paradox posits that both parties to a conflict will rationally view strategic conflict and the attendant risk of a strategic nuclear exchange as untenable, and will thus avoid any escalation of sub-strategic conflicts to the strategic level. This effective “cap” on sub-strategic militarized conflict escalation emboldens states to engage in such conflict with the confidence that it would not spiral out of control and threaten their strategic interests. The causal force of this theory of increased sub-strategic conflict is the mutual recognition of the untenability of conflict at the level of strategic interests—a product of MAD [Mutually Assured Destruction]. With strategic interests forming the “red line” neither side would dare to cross, both sides are free to pursue sub-strategic political objectives through militarized conflict without the fear that the terms of such conflict will escalate beyond their control and jeopardize their strategic interests. Effectively, with the risk of uncontrolled escalation removed, the net costs to engage in conflict are reduced. One of the major assumptions in the concept of mutually assured destruction and the stability-instability phenomenon as its consequence is that all actors are rational and that this rationality implies an avoidance of complete destruction. Particularly the second part of the assumption might not necessarily be given in real-world politics. When imagining a theocratic nation whose leaders believe in the existence of an afterlife which they assume to be sufficiently better than our current life, it becomes rational for them to do everything in their power to facilitate a swift transition for as many people as possible into that afterlife. This connection between certain religious beliefs and politics of weapons of mass destruction has been pointed out by some atheists in order to point out perceived dangers of theocratic societies.

Then there is the nuclear secret at the heart of the financial economy – the Kalevala – making Bujak Oscillationists of the best of us, a finiverse forever alternating between its Big Bang and its Big Crunch – expansion and collapse, gravity, the shakespearean arc, tragedia/commedia, onsheet balances and offsheet exposures, yin and yangs, light and dark, waiting for that moment when things start turning on their hinges, light travelling backward, pouring out from human eyes, and it has a cooling effect, sobering, as time leaks but I still don’t understand the New Normal, when what before was not normal, society’s far weirder, beamed, oscillationist, nucleareously poised on fine ledges between heights and depths, that are their own bright inversions.

What is happening with technology, what is happening with the war-machine in the heart of industrial sociery? What is happening with development or nondevelopment, etc.? That should be the real debate. I don’t deny the importance of the return of the sacredbecause, in reality, it was caused by the nuclear age. The nuclear age has put us closer to the apocalypse-this time as the extinction of the species. It’s hardly surprising that religious beliefs are unfurling their nags-whether it be Islam, Israel, Jerusalem, “the Eternal City,” or the Christian banner. I would say it’s perfectly under standable, because facing them is a superb idol they can’t accept. I’m a believer, but I’m also political. I believe we need to work on technology, on the essence of technology, as Heidegger said-and thus on the essence ofwar, that is, the essence ofspeed. I’ll finish with two great phrases by Sun Tsu: “Readiness is the essence of war.” What foresight five centuries before Christ. And the second: “Military strength is regulated on irs relation to semblance” everything that has to do with ideologies, hide-and-seek, telecommunications, the impact of audio-visual weapons. That in a nutshell is my account ofthe present situation. But by answering this way, I give no arms to the militants. Personally, I am not a militant; I couldn’t be one. I can only watch and wait.