1962 Oahu.

She dancing in a sun cult, D.H Lawrence, Isadora Duncan,

“When, in its divine power, [the soul] completely possesses the body, it converts that into a luminous moving cloud and thus can manifest itself in the whole of its divinity.” (Isadora Duncan (1877-1927))

Said otherwise, for Duncan, “divinity” is something that we can come to conceive and know only in and through our own bodily movements if and when and as we move with an awakened “soul.” We know “it” through the kinetic images we make of “it” as that which impels us to move. Elsewhere, Duncan locates this kinetic sensibility in the solar plexus. Yet here again, it is not that “the soul” is some spiritual entity that rests under our ribs. Rather, Duncan claims that at the crossing of our own beating and breathing rhythms, we are particularly vulnerable to sensing and receiving and responding to movement impulses. As a result, we can choose to focus our attention on the solar plexus as a way to awaken a sensory awareness capable of pervading a whole bodily self. To awaken soul—to learn to dance—is to know that how we move matters. How we move matters to who we are, what we value, and what the world is able to become through us. Every moment, in every thing we do, we are making the movements that bring the world, our ideals, our values, and even our gods, into being.

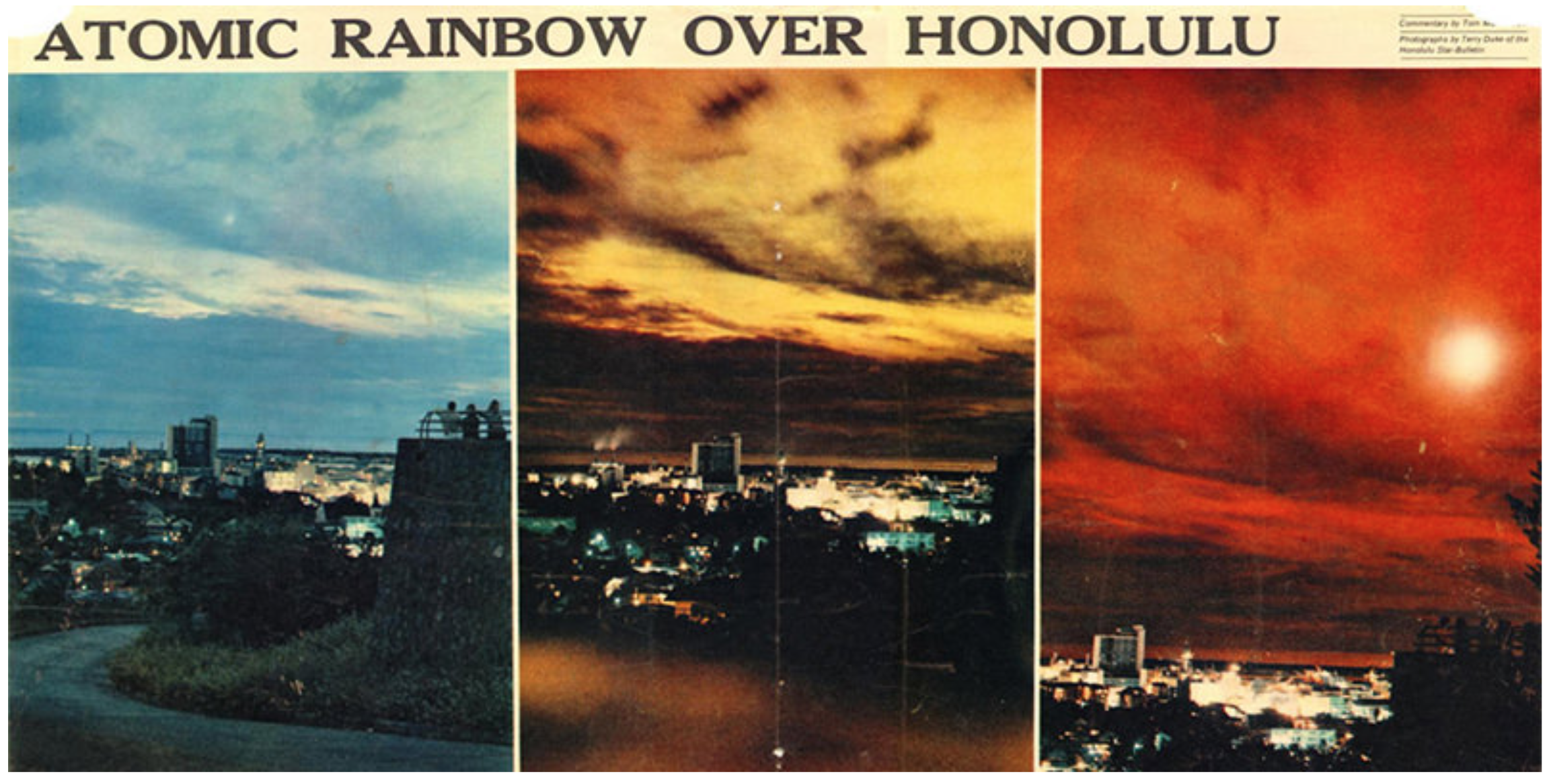

He working on the missile shots in the Pacific. A rainbow party on the rooftop overlooking Starfish Prime…. he had blown in over white Atlantic, Dutch descent, settling in ...

she was born on the stroke of December 1941, days before Pearl Harbour… the no-no boys were being locked up on the West Coast, Okada, flying a B24 from Guam over Tokyo, listening in on Japanese, scrawling on a page…

Korea War… Hiroshima…Ronald Laing…Inouye…Baseball… Turtle the blinded G.I., the 442nd regiment, the longshore strikes, the Union, Martin Luther… she was a Japanese-American born in the era of camps, and no-no. boys… he was an operator on the Operation Dominic Missile tests, with sympathies to the longshore strikes… she reads Beatnik generation, Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg, Albert Saijo a Hawaii local, The Kingston Trio , formed in 1957 in San Francisco, California, Bob Shane (b. Feb 1 1934, Hilo Hawaii); Nick Reynolds (b. July 27 1933 San Diego); Dave Guard (b. Mar 22, 1991 Honolulu, Hawaii); Hawaiian baby wood rose seeds; the Marsh Chapel Experiment; Big Sur, On the Road; she read Steinbeck dustbowl and thought him similar to a new book Things Fall Apart, from that continent west Africa, ‘turning and turning in the widening gyre, the falcon cannot hear the falconer; things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world

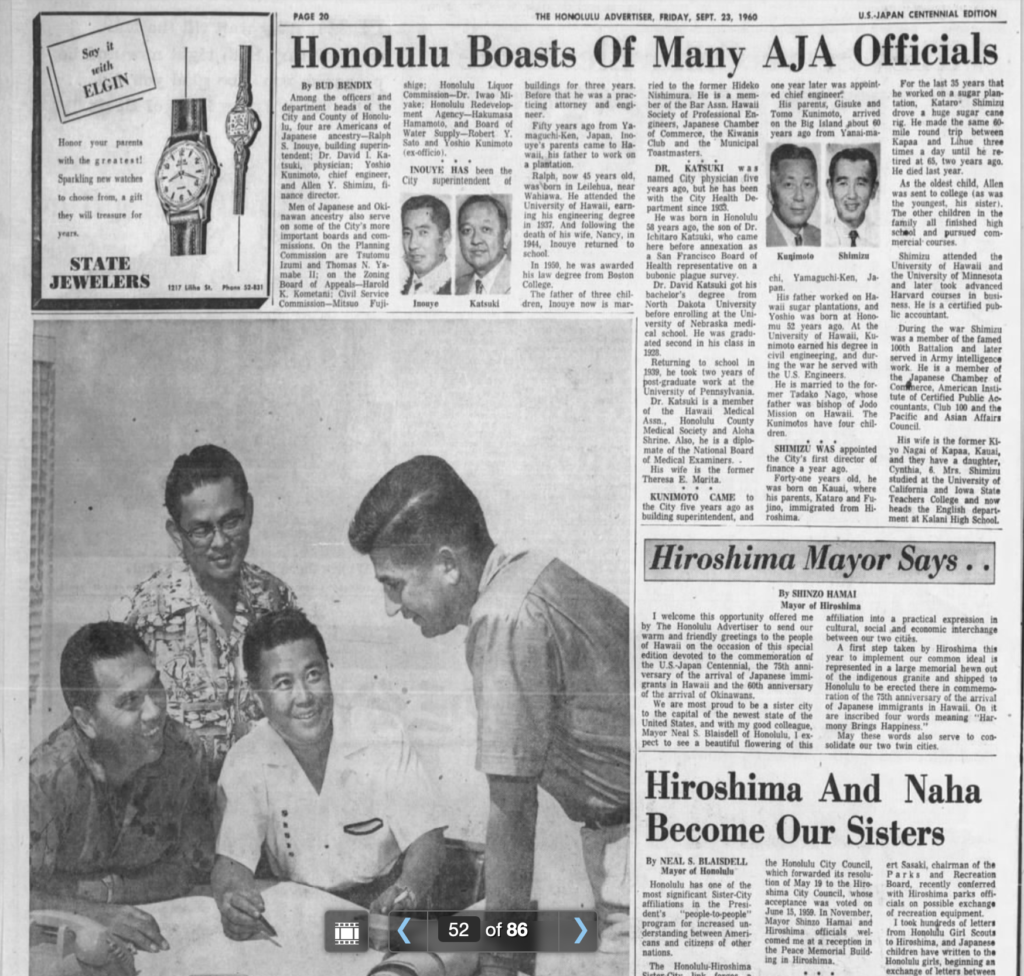

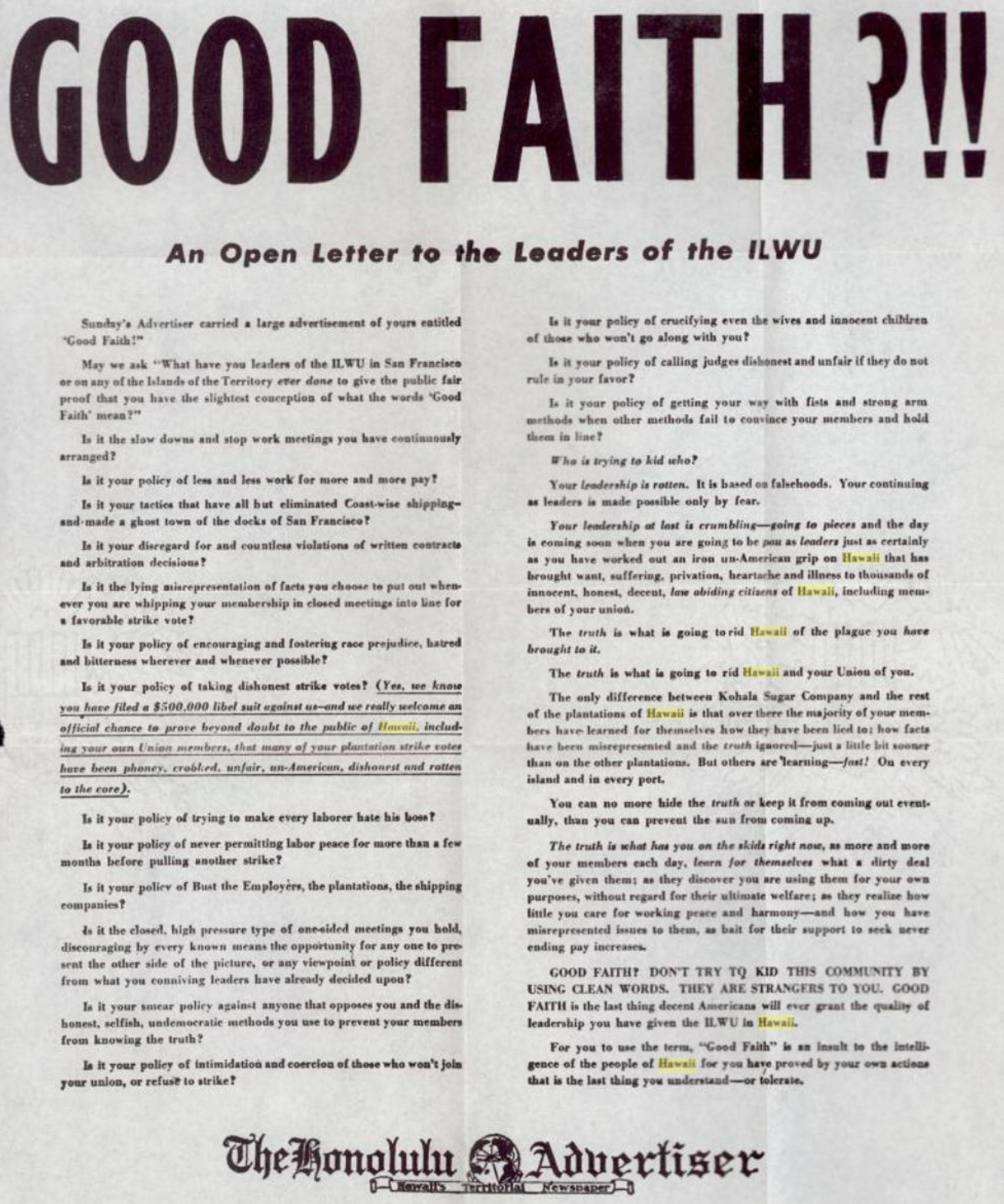

Working a pressman in the Honolulu Advertiser, Ulysseslike, preparing pamphlets…

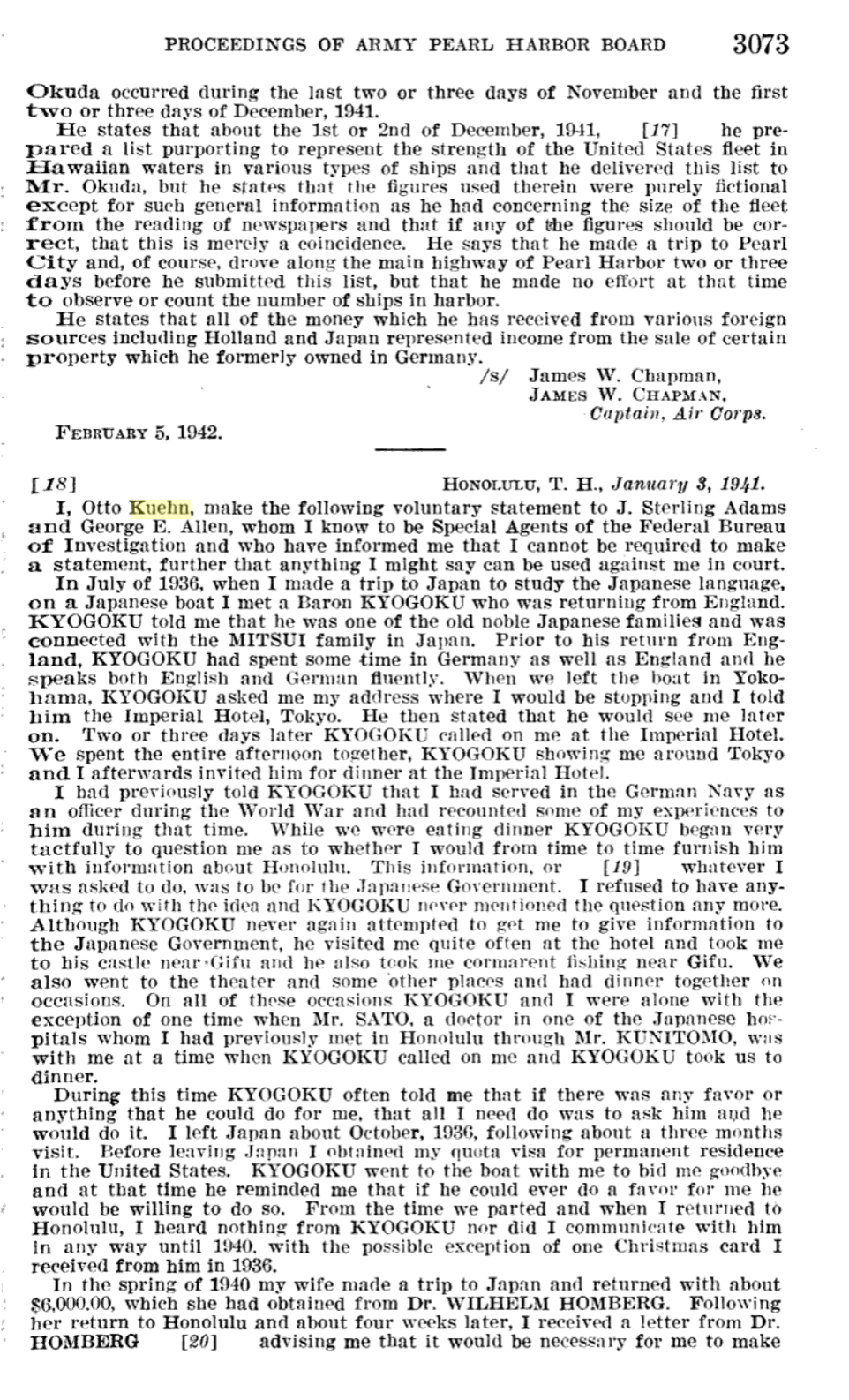

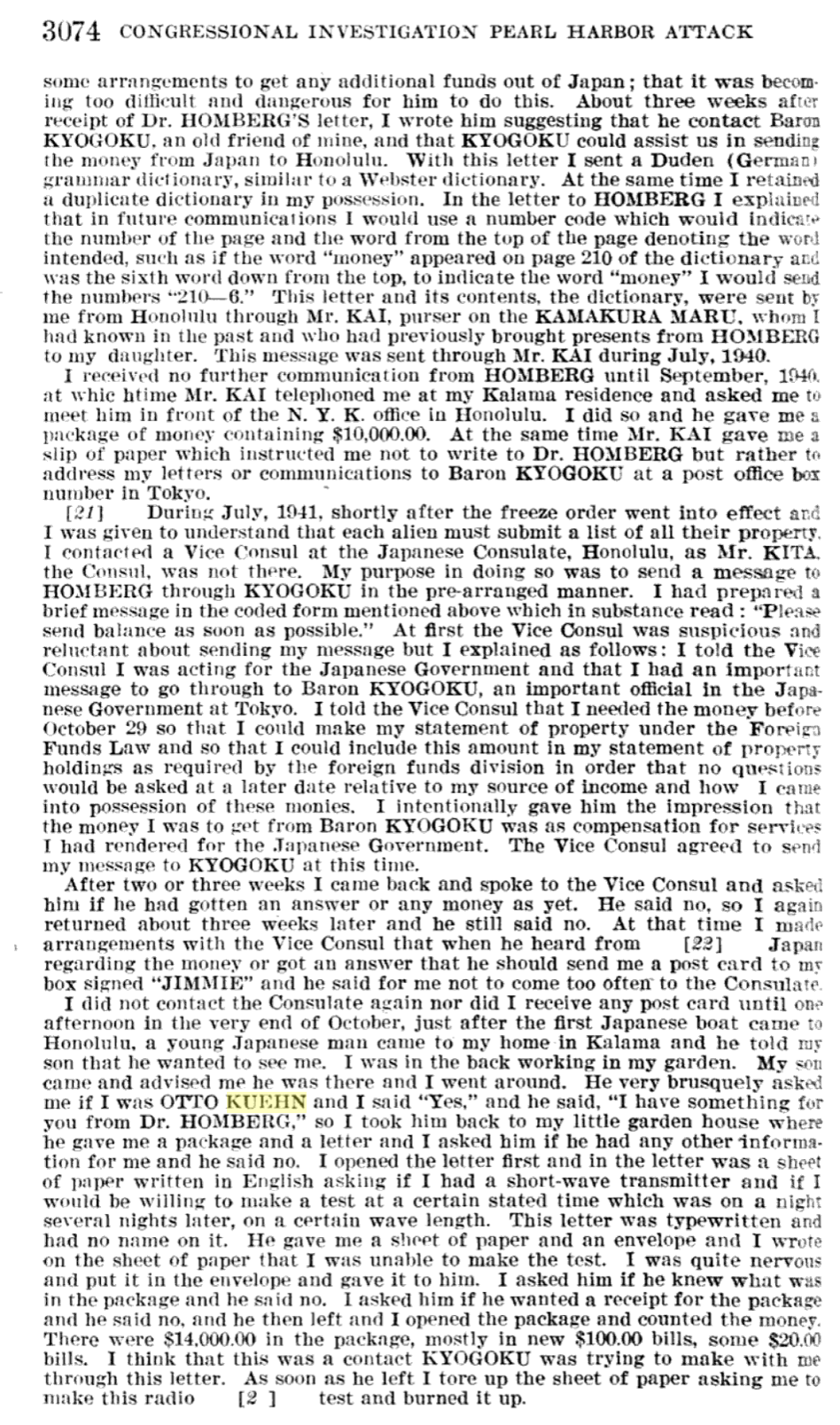

the strange German neighbour who got deported in the war by the name Kuehn…. there were germans here now looking for exotic plants, a Fritz Hoffman.. missile experts… the pill arrived in 1960… she’d heard Martin Luther speak in 59…

It opens in a similar scene to Underworld (DeLillo)… a baseball match… or a longshore strike… or 1959… a crowd…

He speaks in your voice, American, and there’s a shine in the eye that’s halfway hopeful. It’s a school day, sure, but he’s nowhere near the classroom. He wants to be here instead, standing in the shadow of this old rust-hulk of a structure, and it’s hard to blame him – this metropolis of steel and concrete and flaky paint and cropped grass and enormous Chesterfield packs aslant on the scoreboards, a couple of cigarettes jutting from each. Longing on a large scale is what makes history. This is just a kid with a local yearning but he is part of an assembling crowd, anonymous thousands off the buses and trains, people in narrow columns tramping over the swing bridge above the river, and even if they are not a migration or a revolution, some vast shakingg of the soul, they bring with them the body heat of a great city and their own small reveries and desperations, the unseen something that haunts the day – men in fedoras and sailors on shore leave, the stray tumble of their thoughts, going to a game. The sky is low and grey, the roily grey of a sliding surf.

Dec 7 1960…the A bomb photos are released… Dec 16 1960… the Sacramento Solons Baseball team move to Honolulu

_____________________________________

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Saijo

In 1942, when Saijo was 15 years old, he and his family were removed from their California home and imprisoned at Pomona Assembly Center, then transferred to Heart Mountain Relocation Center, as part of the U.S. government’s program of Japanese American internment.[1][3] While at Heart Mountain Saijo attended high school and worked as a janitor.[4] In 1942, Saijo began to write for his high school newspaper, the Heart Mountain Echoes.[5] His first feature article, entitled “Me and December 7”, was published on the first anniversary of the 1941 Attack on Pearl Harbor, and addressed his memories of shock and disorientation surrounding the attack, and his fears that he would be treated differently by non-Japanese friends and teachers as a result.[6] The article also argued against the significance of race and expressed opposition to the Nazi theory of the master race.[7] In his writing of this period, Saijo expressed a commitment to the United States as a melting pot and support for those who volunteered for the U.S. Armed Forces.[8] The historian Michael Masatsugu has argued that while Saijo did challenge the racial essentialistconstruction of Japanese Americans that was used to justify their internment, his arguments regarding the irrelevance of race and his call for Japanese Americans to assimilate were consistent with the approach of the War Relocation Authority (WRA).[8] Masatsugu observes that this was not a coincidence: Saijo and other writers were supervised by WRA officials, and Masatsugu argues that this supervision was a form of surveillance and censorship.[8]

Saijo’s later editorials and features criticized the injustice of internment. These included “Christmas, 1942”, which recounted his experience of his first Christmas at Heart Mountain.[9] He was more explicit in a March 1943 editorial, in which he associated internment with imprisonment and suggested that it was driven by discrimination.[10] Later in 1943 the Echoes, under Saijo’s editorship, called on Japanese Americans to give their backing to Gordon Hirabayashi‘s legal challenge to internment (see Hirabayashi v. United States).[10]

He later remembered internment as an “adventure”, but also as causing the break-up of his immediate family as he and his siblings began to spend more time with their peers.[4] Saijo was part of an early-leave program that commenced before the camps were closed; through a War Relocation Authority program he moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he hoped to attend the University of Michigan but instead took a job in a cafeteria.[11]

He was eventually drafted,[11] and served in the 100th Battalion of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.[12] He trained in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and served in Italy during the post-war occupation.[11] While serving he contracted tuberculosis, which continued to trouble him for the following 20 years.[11]

In around 1954 Saijo began to develop an interest in Zen Buddhism, and in 1957 he left USC and moved to San Francisco, where his interest in Zen and haiku brought him into contact with members of the Beat Generation.[14] He worked at the YMCA in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and attended courses delivered there by David Hunter of the Human Potential Movement, where he met Lew Welch; and through Welch he met Allen Ginsberg, Joanne Kyger, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen and others.[15] Saijo eventually moved in with Welch, Whalen, and others, and in 1959 led meditation at Snyder’s zendo in Marin, California.[15] Masatsugu argues that Saijo’s emergent interest in his Japanese heritage, including haiku and Zen, and his involvement in the Beat Generation, “were enabled in part by the shift in racial discourse and the re-presentation of things Japanese in American society”,[13] as fears of a “Yellow Peril” receded and Japan became a Cold War ally to the U.S.[11] At around this time Saijo also met Jack Kerouac, who was already an established writer.[15]

Kerouac, Saijo and Welch took a road trip together from San Francisco to New York, during which they bonded over haiku and Buddhism, and composed poems as they went.[16] On arriving in New York, they visited the apartment Ginsberg shared with Peter Orlovsky, where they presented Ginsberg with a wooden cross stolen from a roadside memorial in Arizona. The three men then spent the night at Kerouac’s mother’s house in Northport, where Kerouac remained as Saijo and Welch returned west.[17][18] Trip Trap (1972)[19] is a collection of haiku by Saijo, Kerouac and Welch,[20] which describe their road trip, and invoke Gary Snyder, who was then in Japan, as a kind of guiding spirit.[17]The collection was published after Kerouac and Welch’s deaths, and included an introductory essay by Saijo, in which he recalled their trip as involving shared conversations and shared periods of quiet contemplation.[21]

Funded by the G.I. Bill, Saijo attended the University of Southern California (USC) and earned a bachelor’s degree in International Relations with a minor in Chinese.[13] He entered USC’s graduate program and began work on a thesis on the 1954 partition of Vietnam.[13] Throughout his life Saijo remained in contact with those he had met at Heart Mountain, and relied on these connections for employment, housing, and religious instruction.[13]

Saijo and Kerouac became friends, bound by a shared wanderlust and appreciation of Zen Buddhism, cool jazz and alcohol.[3] Saijo later was a minor character in Kerouac’s Big Sur, in which he takes the name “George Baso” and in Kerouac’s depiction of the 1959 drive is described as “the little Japanese Zen master hepcat sitting crosslegged in the back of Dave’s [Lew’s] jeepster”.[20] Rob Wilson has argued that the character of Baso functions as a “link to Zen Buddhism and the Orient for Kerouac, who found the West Coast U.S.A. closer in expansive sentiment and lyrical existence to Asia than to Europe”.[22] A photograph of Saijo, Kerouac and Welch composing a poem together in New York was featured in Fred McDarrah‘s book The Beat Scene.[23] Along with Shig Murao, Saijo is one of only two Asian-American writers usually considered part of the Beat Generation.[24]

Big Sur is a 1962 novel by Jack Kerouac. It recounts the events surrounding Kerouac’s (here known by the name of his fictional alter-ego Jack Duluoz) three brief sojourns to a cabin in Bixby Canyon, Big Sur, owned by Kerouac’s friend and Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. The novel departs from Kerouac’s previous fictionalized autobiographical series in that the character Duluoz is shown as a popular, published author. The Subterraneans also mentions Kerouac’s (Leo Percepied) status as an author, and in fact even mentions how some of the bohemians of New York are beginning to talk in slang derived from his writing. Kerouac’s previous novels are restricted to depicting Kerouac’s days as a bohemian traveller.

“It was while she and Metzger were waiting for ancillary letters to be granted representatives in Arizona, Texas, New York and Florida, where Inverarity had developed real estate, and in Delaware, where he’d been incorporated. The two of them, followed by a convertibleful of the Paranoids Miles, Dean, Serge and Leonard and their chicks, had decided to spend the day out at Fangoso Lagoons, one of Inverarity’s last big projects. The trip out was uneventful except for two or three collisions the Paranoids almost had owing to Serge, the driver, not being able to see through his hair. He was persuaded to hand over the wheel to one of the girls. Somewhere beyond the battening, urged sweep of three-bedroom houses rushing by their thousands across all the dark beige hills, somehow implicit in an arrogance or bite to the smog the more inland somnolence of San Narciso did lack, lurked the sea, the unimaginable Pacific, the one to which all surfers, beach pads, sewage disposal schemes, tourist incursions, sunned homosexuality, chartered fishing are irrelevant, the hole left by the moon’s tearing-free and monument to her exile; you could not hear or even smell this but it was there, something tidal began to reach feelers in past eyes and eardrums, perhaps to arouse fractions of brain current your most gossamer microelectrode is yet too gross for finding. Oedipa had believed, long before leaving Kinneret, in some principle of the sea as redemption for Southern California (not, of course, for her own section of the state, which seemed to need none), some unvoiced idea that no matter what you did to its edges the true Pacific stayed inviolate and integrated or assumed the ugliness at any edge into some more general truth. Perhaps it was only that notion, its arid hope, she sensed as this forenoon they made their seaward thrust, which would stop short of any sea.”

“They came in among earth-moving machines, a total absence of trees, the usual hieratic geometry, and eventually, shimmying for the sand roads, down in a helix to a sculptured body of water named Lake In-verarity. Out in it, on a round island of fill among blue wavelets, squatted the social hall, a chunky, ogived and verdigrised, Art Nouveau reconstruction of some European pleasure-casino. Oedipa fell in love with it. The Paranoid element piled out of their car, carrying musical instruments and looking around as if for outlets under the trucked-in white sand to plug into. Oedipa from the Impala’s trunk took a basket filled with cold eggplant parmigian’ sandwiches from an Italian drive-in, and Metzger came up with an enormous Thermos of tequila sours. They wandered all in a loose pattern down the beach toward a small marina for what boat owners didn’t have lots directly on the water.” (The Crying of Lot 49)

There was the same whimsy to both. Perhaps—she felt briefly penetrated, as if the bright winged thing had actually made it to the sanctuary of her heart—perhaps, springing from the same slick labyrinth, adding those two lines had even, in a way never to be explained, served him as a rehearsal for his night’s walk away into that vast sink of the primal blood the Pacific. She waited for the winged brightness to announce its safe arrival. But there was silence. Driblette, she called. The signal echoing down twisted miles of brain circuitry. Driblette!”

And there was Mondaugen, chasing the sferics, and the man in the high tower over Alma-Ata, chasing shadows.

Bahman, Szymanski , not chasing Sferics, but satellite tampers, shimmers, blindings, co-orbital deceptions,

“ I’m the projector at the planetarium, all the closed little universe visible in the circle of that stage is coming out of my mouth, eyes, sometimes other orifices also. But she couldn’t let it quite go. “What made you feel differently than Wharfinger did about this, this Trystero.” At the word, Driblette’s face abruptly vanished, back into the steam. As if switched off. Oedipa hadn’t wanted to; say the word. He had managed to create around it the same aura of ritual reluctance here, offstage, as he had on.

“If I were to dissolve in here,” speculated the voice out of the drifting steam, “be washed down the drain into the Pacific, what you saw tonight would vanish too. You, that part of you so concerned, God knows how, with that little world, would also vanish. The only residue in fact would be things Wharfinger didn’t lie about. Perhaps Squamuglia and Faggio, if they ever existed. Perhaps the Thurn and Taxis mail system. Stamp collectors tell me it did exist. Perhaps the other, also. The Adversary. But they would be traces, fossils. Dead, mineral, without value or potential.”

“For one thing, she read over the will more closely. If it was really Pierce’s attempt to leave an organized something behind after his own annihilation, then it was part of her duty, wasn’t it, to bestow life on what had persisted, to try to be what Driblette was, the dark machine in the centre of the planetarium, to bring the estate into pulsing stelliferous Meaning, all in a soaring dome around her? If only so much didn’t stand in her way: her deep ignorance of law, of investment, of real estate, ultimately of the dead man himself. The bond the probate court had had her post was perhaps their evaluation in dollars of how much did stand in her way. Under the symbol she’d copied off the latrine wall of The Scope into her memo book, she wrote Shall I project a world? If not project then at least flash some arrow on the dome to skitter among constellations and trace out your Dragon, Whale, Southern Cross. Anything might help.”

IBManoiacs, and the crew paranoiac who Never saw The War ending, 2020, war continuous, at war in war under war conditions, disappearance, machines saturating into gauze-light, sloterdijk in K bubbles of ambosaccadic terror, Dr. Hilarius with the sirens coming

See Oahu - for structure.

See 7 Dec 1941, Automatic Writing, AQ and Robert - for writing line

footnotes

1962

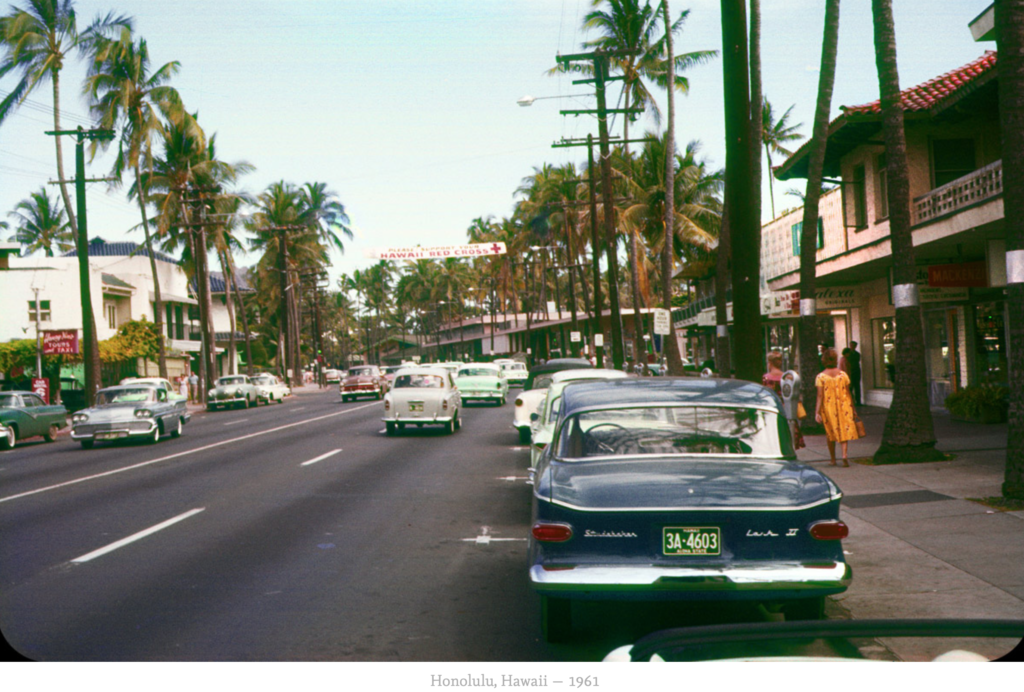

Film Above. This 1960s color travelogue about Hawaii is a long advertisement for sponsor Matson Hotels and Northwest Orient Airlines. Waikiki Beach is panned. The Northwest Airlines Boeing 707 lands. Well-dressed passengers are greeted by Hula dancers. Each passenger receives a lei and a kiss (:57-2:00). Catamarans are beached outside the Moana Hotel. A woman enters her room. The porter is tipped. A waiter brings a pineapple to the room. She walks on the beach in her 1960s two-piece bathing suit (2:01–3:17). A man in a 1960s suit walks the beach to the Surfrider Hotel. He receives two leis and kisses. He enters his room; the porter carries his luggage. The balcony view includes a pretty woman sunbathing (3:18–3:50). The SS Lurline passenger ocean liner approaches; passengers wave. Waiting are Hula dancers and a ukulele player (3:51–4:39). The Royal Hawaiian Hotel is shown from the beach. The new guests wear layers of leis. One wears a 1960s dress and white gloves. The balcony view is the beach (4:40–5:22). A woman in a 1960s two-piece bathing suit learns the Hula. A little boy dances to ukulele players. A pretty woman stands on her surfboard; her handsome male companion falls off. A group of women attend an outdoor flower-arranging class (5:23–7:18). The round swimming pool at the Princess Kaiulani Hotel is shown. Tourists pass a portrait of Princess Kaiulani in the lobby. The mural in the Kahili room is shown. Tourists dine on the terrace. Matson Hotels shown are the Edgewater and The Breakers (7:19–9:10). A lunch buffet of seafood dishes are shown. Tourists relax in lawn chairs. Fashion show dress models wearing white 1960s gloves walk by diners. Cocktails are served in the Captain Cook Bar. Room service brings Planter’s Punches drinks as the couple holds slides up to the lamp to see them (9:11–11:46). A man wears a white dinner jacket and black bowtie; the woman wears an ankle-length 1960s sleeveless dress to the Royal Hawaiian cocktail party. The dining room with white tablecloths is shown. A dancer performs (11:47–14:18). The beach is raked. Chess is played. Natives in loincloths prepare luau food. A man pounds poi (14:19–15:40). Passengers board an Aloha Airlines plane. Food is carried at an evening Hawaiian barbeque at the Kauai Coco Palms Lodge. Waimea Canyon is panned. Horseback riders ride at the Hotel Hana Maui beach. Smoke rises at the Volcano House. Horses are ridden at Parker Ranch. The Waipio Valley is shown (15:41–17:32). Tourists board the Manu Kai catamaran and paddle Polynesian outrigger canoes. Surfboard riders perform. Skin divers harass a turtle (17:33–19:32). Tourists travel by bus in Oahu, with scenic coast views, to Kaneohe Bay. They learn the Hula and pass an orange by neck game, conga, and eat a buffet. Hula and knife dances are performed. Marshmallows are toasted over a fire. A luau at Don the Beachcombers includes dancing performers (19:33–23:54). Passengers throw their leis into the water from the ship. New tourists arrive. Couples dance on the beach under moonlight (24:55–26:25).

Presley arrived in Hawaii on March 18, 1961, to prepare for a charity concert that he was performing on March 25 to raise funds for the Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor.[8] He arrived at the recording studio on March 21 to start the recording of the film’s soundtrack.[8] Three weeks later, location filming had finished, including scenes at Waikiki Beach, Diamond Head, Mount Tantalus, and Hanauma Bay, a volcanic crater that is open to the sea, near the bedroom community of Hawaii Kai, a few miles away from Waikiki.[6][9] Following location filming, the crew returned to the Paramount lot to finish other scenes for the film. Presley would relax during filming by giving karate demonstrations with his friend and employee, Red West, which resulted in Presley’s fingers becoming bruised and swollen. Wallis warned the female stars of the film to avoid parties hosted by Presley because they were turning up for shooting looking tired.[6]

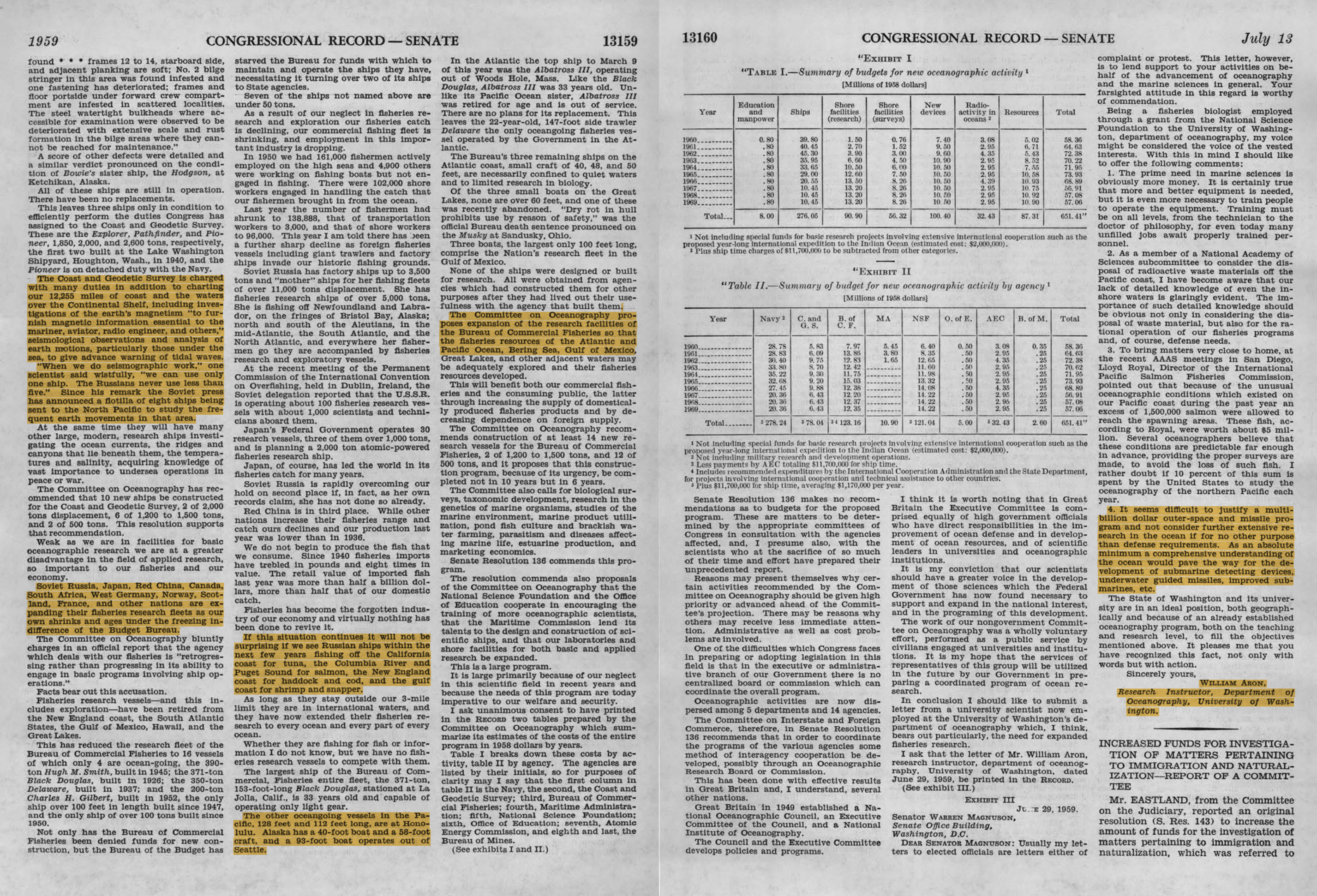

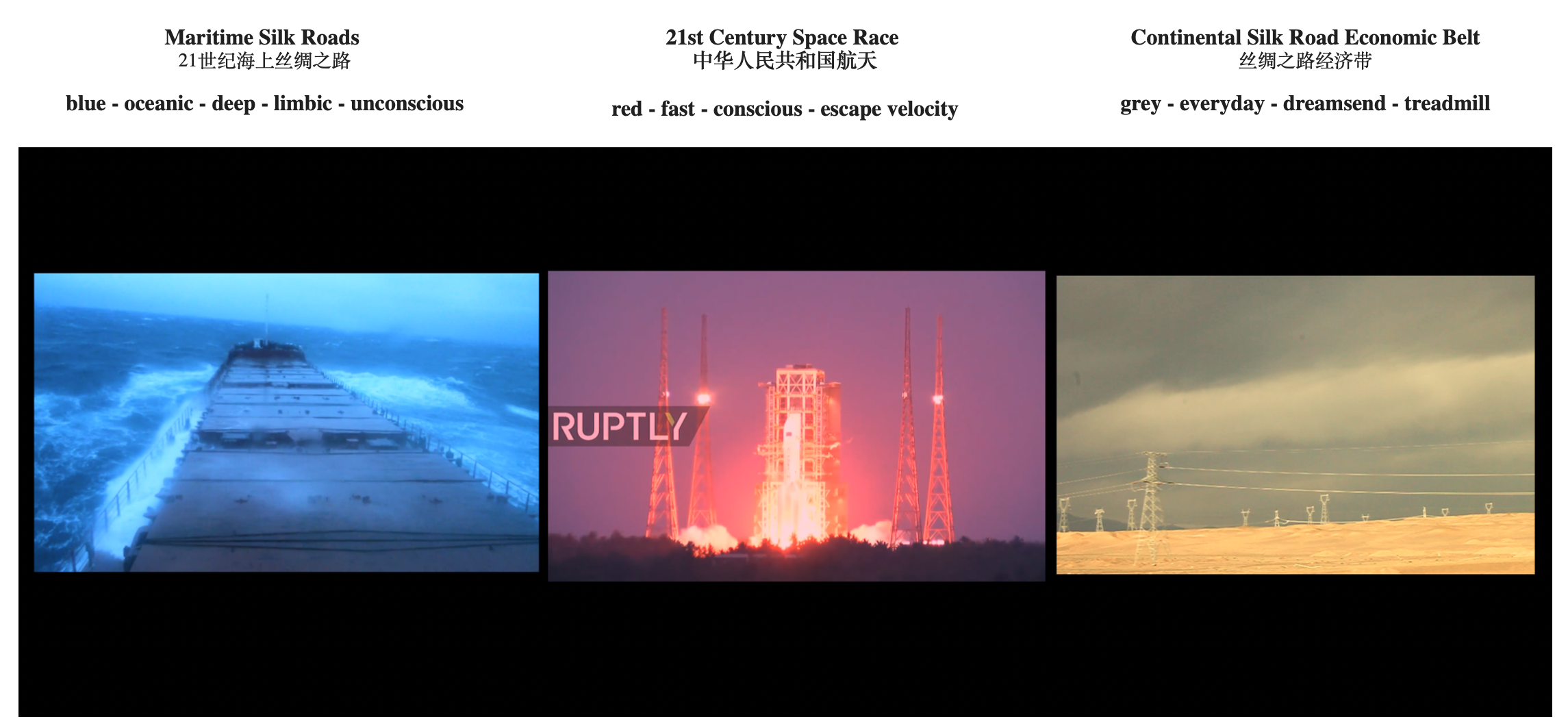

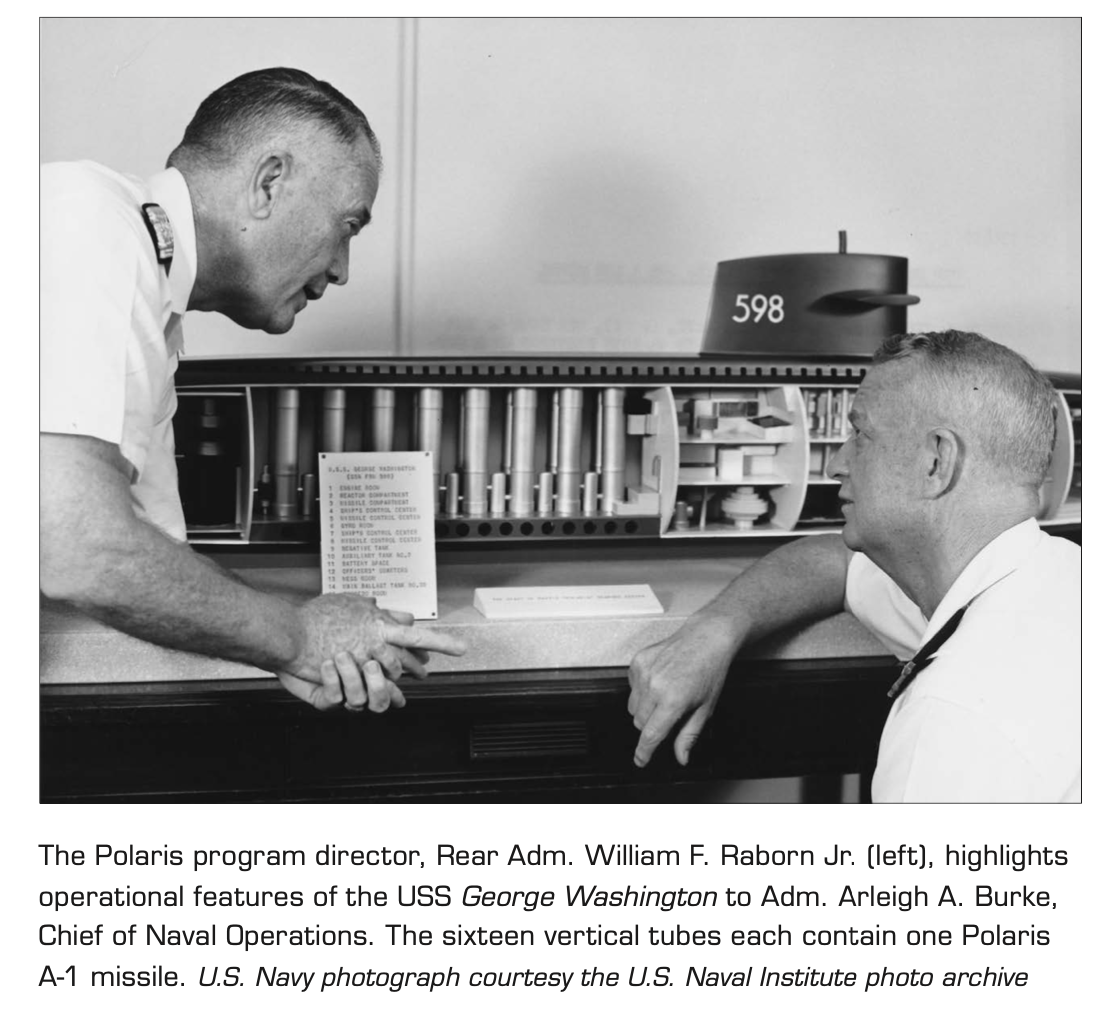

July 9 1962 Starfish Prime (Sphera)

‘N-Blast Tonight May Be Dazzling; Good View Likely’

There are few excuses to drink like mutually assured destruction. That excuse was firmly seized by Hawaiians in the the heat of the Cold War on a summer night in July of 1962. That fateful night, a hydrogen bomb, code-named “Starfish Prime,” was shot above the Earth’s atmosphere and detonated, causing a nuclear light show of colors. It was tragically beautiful, and also the occasion of some supreme partying. Throwing a party while the world collapses isn’t a new or rare occurrence. Just look at the speakeasies of the 1920s and 1930s, where flappers danced and bathtub gin flowed while crime proliferated and the Lost Generation wandered. Or the clubs of New York City in the 1980s that continued on through the AIDS epidemic. In this case, the party and the threat of destruction joined together for a spectacular show. The front page of The Honolulu Advertiser announced the detonation in no uncertain terms. “N-Blast Tonight May Be Dazzling: Good View Likely,” it declared, referencing the imminent nuclear explosion. Beachfront hotels and rooftop bars, some 800 miles away from the launch site, threw “Rainbow Bomb Parties” to celebrate the event, simultaneously beautiful yet possibly also signaling the end of humanity as they knew it. When faced with signs of destruction, sometimes the best thing to do is raise a glass and enjoy the view.

But the story of these nuclear parties begins four years earlier, in 1958. A scientist named James Van Allen had discovered that the Earth is surrounded by belts of high-energy particles held in place by magnetic fields, according to NPR. To this day, those belts are known as Van Allen Belts. The day after the announcement of the belts, Van Allen joined the military in a project to try to disrupt the magnetosphere around Earth with atomic bombs. The military wasn’t out to create a light show for a new type of nuclear party. They wanted to see if radiation could obscure Russian missiles, damage nearby objects, alter the Van Allen belts, or if the explosion could hit a target on Earth. The Soviet Union asked for a ban on atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons in 1958, which would have scuttled the military’s plan with Van Allen, but in 1961, the ban fell apart. Enter Project Fishbowl: the end-all-be-all test of the impact nuclear weapons can have when detonated in space. Within a year of the ban becoming a moot cause, the U.S. was ready to launch Starfish Prime into the atmosphere and give the show of a lifetime for Honolulu partiers.

Seconds after 11 p.m. Hawaiian local time, the equivalent of 1.4 million tons of TNT exploded in space. The H-bomb shot heat, light, radiation, and subatomic particles into the Van Allen Belts above the Earth’s atmosphere. Those particles collided with oxygen and nitrogen atoms, transferring energy that was then released as light. Oxygen higher up in space set off a red light, green a little farther down, and then blue light even farther down where there are more nitrogen atoms. For a sense of what it looked like to the naked eye, think of the light show as a tropical version of the aurora borealis around the North and South Poles. The natural colors come from solar wind hitting the Earth and causing the same effect. It’s also very, very cold to watch the aurora borealis in person. The colors from Starfish Prime were more violent than the solar wind, though. The sky filled with all three colors all at once, creating a rainbow and giving rise to the name, “Rainbow Bomb Party.” It also was tropically pleasant to watch in person. The show lasted for seven minutes. The electromagnetic pulse from the blast blew out streetlights and knocked telephones offline. Garages acted erratically, opening and closing on their own. Radios went dark. But for those seven minutes, the focus was on the sky. People could forget the nuclear bomb drills in school, the artists and politicians being rounded up under McCarthyism, and the new war in Vietnam. Because sometimes, the best thing to do in the face of destruction is throw a party. (Source: https://vinepair.com/articles/that-time-we-blew-up-a-nuclear-bomb-as-a-party-trick/)

See also https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/going-nuclear-over-the-pacific-24428997/

Wednesday December 7 1960 - Pictures of Japan A-Bombs Released

This Honolulu Advertiser announcement of Barack Obama’s Aug 4, 1961 birth was published August 13, 1961 on page B-6. It is available only on microfilm in Hawaii libraries. The announcement is 4th from the bottom of the left hand column.

‘Far down to the right a thin line of coconut palms marked the new Western edge of America, a lonely-looking wall of jagged black lava cliffs looking out on the white-capped Pacific’ – Hunter S. Thompson, The Curse of Lono (photographs below: https://flashbak.com/1960s-hawaii-in-kodachrome-411751/)

May 23 1960

On May 23, 1960, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion announces to the world that Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann has been captured and will stand trial in Israel. Eichmann, the Nazi SS officer who organized Adolf Hitler’s “final solution of the Jewish question,” was seized by Israeli agents in Argentina on May 11 and smuggled to Israel nine days later. In May 1960, Argentina was celebrating the 150th anniversary of its revolution against Spain, and many tourists were traveling to Argentina from abroad to attend the festivities. The Mossad used the opportunity to smuggle more agents into the country. Israel, knowing that Argentina might never extradite Eichmann for trial, had decided to abduct him and take him to Israel illegally. On May 11, Mossad operatives descended on Garibaldi Street in San Fernando and snatched Eichmann away as he was walking from the bus to his home. His family called local hospitals but not the police, and Argentina knew nothing of the operation. On May 20, a drugged Eichmann was flown out of Argentina disguised as an Israeli airline worker who had suffered head trauma in an accident. Three days later, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion announced that Eichmann was in Israeli custody.

A tsunami caused by an earthquake off the coast of Chile travels across the Pacific Ocean and kills 61 people in Hilo, Hawaii, on this day in 1960. The massive 9.5-magnitude quake had killed thousands in Chile the previous day. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11 p.m. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly. The Pacific Tsunami Warning System, established in 1948 in response to another deadly tsunami, worked properly and warnings were issued to Hawaiians six hours before the wave’s expected arrival. Some people ignored the warnings, however, and others actually headed to the coast in order to view the wave. Arriving only a minute after predicted, the tsunami destroyed Hilo Bay on the island of Hawaii. Thirty-five-foot waves bent parking meters to the ground and wiped away most buildings. A 10-ton tractor was swept out to sea. Reports indicate that the 20-ton boulders making up the sea wall were moved 500 feet. Sixty-one people died in Hilo, the worst-hit area of the island chain. The tsunami continued to race further west across the Pacific. Ten thousand miles away from the earthquake’s epicenter, Japan, despite ample warning time, was not able to warn the people in harm’s way. At about 6 p.m., more than a day after the earthquake, the tsunami struck the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido. The crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages.

Beatnik, Big Sur, LSD, Hawaiian Baby Woodrose conspiring

The Curse of Lono (Howard S. Thompson) / Americana (Don DeLillo)

DeLillo’s protagonist, a filmmaker and successful television executive, interacts with the world around him by converting it to images, straining it through the lens of his sixteen millimetre camera. He attempts to recapture his own past by making it into a move, and much of the book concerns this curious, Godardesque film in which, he eventually discloses, he has invested years. Thus one encounters – two years before the conceit structured Gravity’s Rainbow – a fiction that insists on blurring the distinctions between reality and its representation on film. Film vies, moreover, with print, for readers must negotiate a curiousy twinned narrative that seems to exist as both manuscript and “footage” – and refuses to stabilise as either.

they were swept up in the revolutionary feel underfoot

The Mechanization and Modernization (M&M) Agreement of 1960 was an agreement reached by California longshoremen unions: International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), and the Pacific Maritime Association. This agreement applied to workers on the Pacific Coast of the United States, the West Coast of Canada, and Hawaii. The original agreement was contracted for five years and would be in effect until July 1, 1966. ILWU signs Mechanization and Modernization Agreement, which pioneers the tradeoff of members’ job security for the employers’ right to introduce labor-saving equipment. On September 22, 1959, King visited Punahou at the invitation of President John Fox. At an Academy Chapel, he preached to our students on the “Three Dimensions of Life,” a topic that he would return to repeatedly during the struggle for civil rights. While we don’t have the precise text he used that day, in later versions of the same sermon he reflected on the vital interrelationship between self-acceptance, love of others, and faith in God. Most crucially, King called on his audience to cultivate a spirit of gratitude and recognition of interdependence that might allow them to “rise above the narrow confines of . . . individual concerns.” “This is what God needs today,” he emphasized, “men and women who will ask, ‘What will happen to humanity if I don’t help?’”

The Hawaii Democratic Revolution of 1954 was a nonviolent revolution that took place in the Hawaiian Archipelago consisting of general strikes, protests, and other acts of civil disobedience. The Revolution culminated in the territorial elections of 1954 where the long reign of the Hawaii Republican Party in the legislature came to an abrupt end, as they were voted out of the office to be replaced by members of the Democratic Party of Hawaii. The strikes by the Isles’ labor workers demanded similar pay and benefits to their Mainland counterparts. The strikes also crippled the power of the sugarcane plantations and the Big Five Oligopoly over their workers. Hawaii had a dominant-party system since the 1887 revolution. The 1887 Bayonet Constitution took most of the power away from the monarchy and allowed the Republican Party to dominate the legislature. Besides a brief change of power to the Home Rule Party following annexation, the Republicans had run the Territory of Hawaii. The industrialist Republicans formed a powerful sugar oligarchy, the Big Five. During the controversial Kahahawai murder and trial Republicans displayed their power by reducing the 10-year sentence for manslaughter to one hour. Many felt the trial was a failure of justice from political forces. But this was not the only case of the government’s abuse of power; past misdeeds were mainly centered around economic gain. Among the unhappy residents of Hawaii was John A. Burns, a police officer during the trial.[1]Burns founded a movement by collecting support from the impoverished sugar plantation workers. He also restored strength to the divided and weak Democratic Party of Hawaii. After the war, Burns was able to gain support from Japanese American veterans of the 100th and 442nd returning home.[5] He encouraged the veterans to become educated under the G.I. Billand to run for public office. Daniel Inouye, who would become a very prominent US senator, is considered the first of the veterans he recruited and was a prominent member of the movement. Hall and Kawano’s strikes resumed after the war. The ILWU helped to organize the plantation workers spreading unionization from the sea to the land. This allowed the movement to organize general strikes in the sugar industry and pineapple industry, not just strikes at the docks. The Hawaiian sugar strike of 1946 was launched against the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association and the Big Five leaving the cane fields derelict. The 1947 Pineapple Strike followed on Lanai but ended in failure and was tried again in 1951. The 1949 Hawaiian Dock Strike froze shipping in Hawaii for 177 days, ended with the territorial Dock Seizure Act.[6]

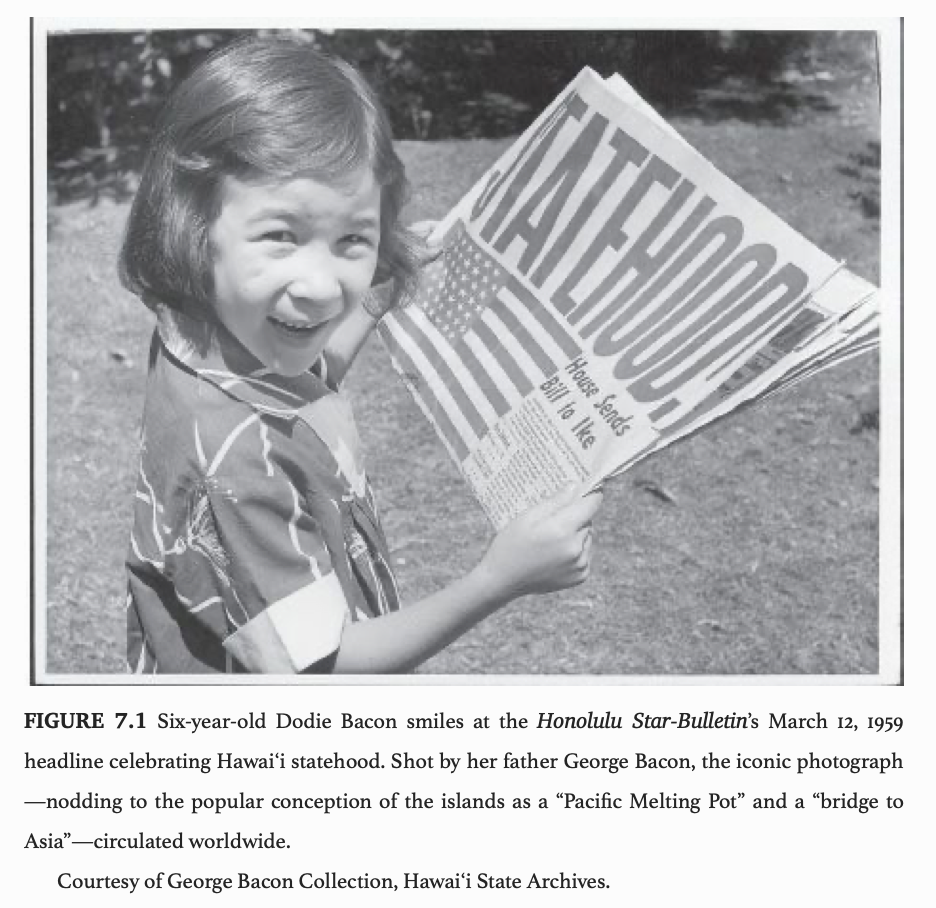

As the movement developed the more communist components began to show through. The strikes were increasingly politicized and at the 1949 strike the White Republican aristocracy who were owners in the Big Five became concerned over the communist trend by workers.[7] On October 7, after the 1949 dock strike that year, the territorial legislature requested the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate the strikes that had become frequent in the territory.[8] On August 28, 1951, the FBI rounded up seven members of the movement[9] including Jack Wayne Hall, Charles Fujimoto (chairman of the Communist Party of Hawaii), and Koji Ariyoshi (editor of the Honolulu Record), who had also published pro-communist work. The Hawaii 7 were charged under the Smith Act for conspiring to overthrow the government; all were released by 1958. The first Congressional bill for Hawaii statehood was proposed in 1919 by Kuhio Kalanianaole,[28] and was based upon the argument that World War I had proved Hawaii’s loyalty.[29] It was ignored, and proposals for Hawaii statehood were forgotten during the 1920s because the archipelago’s rulers believed that sugar planters’ interests would be better served if Hawaii remained a territory.[30] Following the Jones-Costigan Act, another statehood bill was introduced to the House in May 1935 by Samuel Wilder King but it did not come to be voted on, largely because FDR himself strongly opposed Hawaii statehood,[31] while “Solid South” Democrats who could not accept non-white Congressmen controlled all the committees.[32] Hawaii resurrected the campaign in 1940 by placing the statehood question on the ballot. Two-thirds of the electorate in the territory voted in favor of joining the Union.[33] After World War II, the call for statehood was repeated with even larger support, even from some mainland states. The reasons for the support of statehood were clear: Hawaii wanted the ability to elect its own governor; Hawaii wanted the ability to elect the president; Hawaii wanted an end to taxation without voting representation in Congress; Hawaii suffered the first blow of the war; Hawaii’s non-white ethnic populations, especially the Japanese, proved their loyalty by having served on the European frontlines; Hawaii consisted of 90% United States citizens, most born within the U.S. A former officer of the Honolulu Police Department, John A. Burns, was elected Hawaii’s delegate to Congress in 1956.[34] A Democrat, Burns won without the white vote but rather with the overwhelming support of Japanese and Filipinos in Hawaii. His election proved pivotal to the statehood movement. Upon arriving in Washington, D.C., Burns began making key political maneuvers by winning over allies among Congressional leaders and state governors. Burns’ most important accomplishment was convincing Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson (D-Texas) that Hawaii was ready to become a state, despite the continuing opposition of such Deep Southerners as James Eastland[35] and John Sparkman. In March 1959, both houses of Congress passed the Hawaii Admission Act and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law. On June 27, 1959, a plebiscite was held asking Hawaii residents to vote on accepting the statehood bill. The plebiscite passed overwhelmingly, with 94.3% voting in favor.[36]On August 21, church bells throughout Honolulu were rung upon the proclamation that Hawaii was finally a US state.

Though the ground was eroding beneath his feet as ILWU membership dwindled, Jack Hall continued to be a major player in Hawai‘i. Sanford Zalburg, his biographer, recalls that it was not unusual when Hall summoned other (p.332) leading figures like John Burns, Art Rutledge, and Daniel Inouye to his abode and “laid down the law to them.” When presidential candidate Richard Nixon arrived in Honolulu in 1960, he met with Hall in Kapiolani Park. “I know,” said Hall’s spouse. “I drove him up there. I was laughing all the way. It was just like cops-and- robbers,” she recalled, recounting their dodging the press. “He wanted me to take the most devious route.”141 Nixon, a renowned anticommunist, was chagrined about feeling compelled to kiss the ring of a reputed Red, which explained why Yoshiko Hall delivered her husband to him via a circuitous route. Her intentional misdirection was not unique to her. Typically, the union wrong-footed its opponents; for example, in 1956 Bridges registered as a Republican, which “really confused and confounded a lot of people out of our ranks,” a pleased Hall wrote to Goldblatt, adding: “Good Stuff.”142

Fighting in Paradise: Labor Unions, Racism and Communists in the Making of Modern Hawaii (Gerald Horne, 2011)

This introductory chapter discusses the background of Hawaii’s labor movement, in particular the International Longshore and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) and its ties to the Communist Party. It details the dock workers’ strike in June 1953, roughly three years after the United States embarked on a bloody war on the Korean peninsula and Hawaii became a primary point of departure for supplying the battlefield of this anticommunist conflict. It argues that the prolonged repression of workers contributed to pent-up resentment that burst forth with the efflorescence of labor organizing, notably by the ILWU. In 1953, Hawaii had a population of about 500,000, and the ILWU membership was about 24,000, including the stevedores—soimportant for the unloading of merchandise in the island chain that was 2,400 miles from North America. Because of the varied influences of seafarers who frequently visited these islands and stevedores influenced by the ILWU, Hawaii long had developed a justified reputation for working-class consciousness, which the union was able to parlay into major gains.

The workers kept coming, streaming in rivulets of protest. These men—they were mostly men— were predominantly of indigenous Hawaiian, Filipino, and Japanese origin and were departing angrily from the docks of pleasant Honolulu and balmy Hilo and the plantations of Kaua‘i and Lana‘i. It was in the early afternoon in mid-June 1953, roughly three years after the United States had embarked on a bloody war on the Korean peninsula and Hawai‘i had become a primary point of departure for supplying the battlefield of this anticommunist conflict. Yet these men who numbered in the thousands were protesting, since their union leadership and the Communist Party leadership, which were thought by their adversaries to be equivalent, had been convicted on anticommunist grounds of violating the notorious Smith Act. The docks, usually a beehive of activity in light of the jolt provided by war contracts, were strangely silent, as if the men had been summoned by a modern Pied Piper. Though closer to Osaka than Boston and considered relatively isolated, the ports of Hawai‘i were among the most efficient in the world when it came to handling cargo, and with harbor entrances directly facing the Pacific Ocean, their importance increased as military tensions waxed in Korea – then Vietnam – and tensions rose accordingly.

In protest of the conviction of the seven leftist leaders, and, most particularly, their leader. – Jack Hall – stevedores voted quickly to virtually double their wage demands in current contract negotiations. Ships were being stranded in port, and sugarcane and pineapple began to decompose in the field. This was not the first time that Hawai’i workers had gone on strike in reaction to a slight against a presumed Communist. The same thing occurred in August 1950 after the jailing of these workers’ union leader, the Australian-born Harry Bridges, head of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), based in San Francisco. Then about 10,000 workers went on strike; this time the workers decided to up the ante, as 20,000 walked out. The influence of figures like Bridges caused Senator James Eastland of Mississippi, who took a keen interest in the territory’s affairs, to claim in 1956 that “‘the power of the Communists in Hawaii is a thousand times stronger than it is in the continental United States.’

Many of the Filipinos had experience in one of the more sophisticated guerrilla operations in this planet’s history—the fabled Huk Rebellion35—and Tokyo had long been the site of vigorous and thriving socialist and Communist movements that dwarfed their counterparts in the United States. When the Hawai‘i Communist leadership was placed on trial in 1952, the prosecution introduced an article penned by the legendary Sen Katayama, who had been a founder of the Communist Party in the United States in addition to being a leader of the party in Japan. In the article, he termed Hawai‘i as “the strategic knot of the Pacific” and “the most important strategic point in the Pacific Ocean”; given that fact, he was elated to note, “Among the Japanese workers in Hawaii there was a group which was long under the influence of the Japanese revolutionary movement. The members of this group came chiefly from the Japanese islands of Riu-Kiu [Ryukyus], where, at one time, the Japanese Workers and Peasants Party (which supported the CP [of] Japan and was dissolved by the government in 1928) had a strong influence.”36 An article retained by Senator Hugh Butler of Nebraska spoke dramatically of a “Japanese Communist Master Plan” in pursuit of the “Japanization of Hawaii.” This scheme “progressed so well,” said the writer, “that a notable Communist, Hozumi Ozaki, succeeded in penetrating to become an unofficial advisor to the Japanese Cabinet on the eve of Pearl Harbor. He was a trusted intimate of Prince Fumimaro Konoye, the Premier.” As he saw things, it was the CP in Tokyo—not Moscow—that “threatens the entire world.”37 Weeks before war erupted on the Korean peninsula, Senator Butler received from Hawaiian attorney James Coke a picture with a caption he found disturbing: “200,000 … in the Imperial Plaza in Tokyo to hear Japan’s Communist Party leader, Sanzo Nozaka, deliver his May Day Address.”38

Many of the most militant workers in Hawai‘i hailed from the radical region singled out by Katayama. “I’m an Okinawan,” said Yasuki Arakaki, one of the more dedicated of ILWU members during its pre-statehood heyday. “As I was growing up, I knew I was not Japanese. I was not treated as Japanese.” Like minorities worldwide who felt a deep sense of grievance—including African-Americans on the mainland—this helped to generate within him a fierce progressivism. “So when a person is discriminated [against] …, you have a feeling of fighting back, you know.” Thus, he continued reflectively in a 1991 interview, “if you see today, many of the business people on the Big Island [Hawai‘i], the Kaneshiro family, the Food Fair, and many of the merchants in Honolulu, the Star Market, many of the markets [are owned by] Okinawans. And Okinawans[,] because they are discriminated [against], they stick together and help each other out.” Once he had a would-be sweetheart whose mother compelled (p.6) her to reject him, “‘because you’re an Okinawan,’” he was informed curtly. He was “deeply hurt[,] naturally,” as he felt like a “low-class Japanese.” But dialectically, he said, “that gave me some impetus to prove that I’m not a leper. I’m going to prove to her and others that I’m equal or better”39—which he did by becoming one of the leading unionists in the archipelago, as did other similarly situated Okinawans.

Contemporary Euro-American writer Susanna Moore, who grew up in pre-statehood Hawai‘i, has asserted that in Hawai‘i “there was a fairly unconscious racism all around us” and also quite a bit of this bile that was (p.12) “institutionalized” in the form of “restrictions and bylaws that kept non-haoles not only from private clubs, but from certain neighborhoods.” In that era this praxis was largely ‘unquestioned’ – at least by the White minority. Senator Butler of Nebraska discovered this when he began his post–World War II assessment of whether Hawai‘i should become a state. Lucile Paterson, a resident of Honolulu informed him that the “much bruited racial integration and mutual respect” was “largely a myth”; she perceived an “undercurrent of hostility against the haoles or whites by the mixed Oriental population.” As she saw it, the “numerous ‘hoodlum attacks’” then capturing headlines were symptomatic of “Orientals vs. haoles” since the latter were targeted in her eyes. “My son is an excellent barometer,” she said with regret. “He came here totally unaware of ‘race’ as such [but] he has already acquired a wary manner in his dealing with Orientals of his own age and has finally accepted the fact that he is a ‘damn haole.’”75 When Senator Butler held confidential hearings in 1948 in Honolulu on the prospects for statehood, he was greeted with an outpouring of nervous sentiment from whites who, despite their privileged position, complained repeatedly about racial harassment. Like many of the witnesses, Francis D. Houston opposed statehood—if Hawai‘i, why not Fiji? he asked querulously —and asserted that white sailors and soldiers were special victims of physical attacks, as if, to non-haoles, they were symbols of the colonial status that Hawai‘i endured. “Non-haoles [would] catch a haole sailor alone and beat him up.

Though historians have cast serious doubt on the alleged disloyalty of Japanese-Americans during the Pacific War, many whites disagreed vehemently. (p.13) Martin E. Alan, who told Senator Butler of his wonderment as to why so many white Communist men—including Smith Act defendants Jack Hall and John Reinecke and, ultimately, Bridges himself—were married to women of Japanese origin also claimed that farmers of Japanese origin in Hawai‘i had stopped growing vegetables after 7 December 1941 in order to sabotage the war effort. Alan also declared that “from 1920 to 1940 an average of $1,200,000.00 annually was sent to Japan by the nationals here, in the form of gold and silver coin.” As he recalled things, “Planes and submarines made regular and periodic visits here [from Japan] until the very end of the war in 1945. It’s all hogwash about the loyalty of the Niseis [Japanese-Americans] and the aliens,” as there “were acts of sabotage, plenty of them.” But now, he asserted, those of Japanese origin had shifted from allegiance to Tokyo to allegiance to Moscow, for “Communism is working through At the time, there were also pressing regional matters that occupied the grave attention of the archipelago generally. For at that juncture France was exploding nuclear devices in the South Pacific, frighteningly close to Hawai‘i’s shores. The awesome and deadly mushroom cloud was seen by residents of Honolulu as the sky was lit hellish red: how could the union ignore foreign policy or the world beyond the United States, given such threats?78

Because of the diversity of its membership, the union had to be alert to the exchange rate of the dollar with the yen and the Filipino peso. Unsurprisingly, Miyagi was trying to establish closer ties with Asian unions, a matter that was facilitated by the fluency of certain members in Japanese and other languages. Still hanging fire as statehood approached was the question of whether union stevedores would be allowed to unload military material destined for foreign battlefields – 450 tonnes of dynamics was the explosive matter at issue in late 1957. Continuing a long-standing pattern, the ILWU’s most significant global engagement was with Cuba. Shortly after the Cuban Revolution—and just before statehood—Jeff Kibre was seeking a meeting with sugar workers there, but nothing jelled, he reported. “Castro is moving in several different directions at once,” he said, “apparently trying to appease our State Department while at the same time pushing for domestic reforms.”85 Just before that, the ILWU had displayed its solidarity with those seeking to dislodge the US-backed regime when it refused to confer with a Cuban sugar agent in Hawai‘i; the agent was affiliated with a firm that McElrath described as having “the largest holdings of sugar in the western hemisphere”—yet the union, he said, “could not and would not rub shoulders with Cuban sugar.”86

Though the ILWU was castigated by its detractors as being in a relationship of ventriloquism with Moscow, this accusation hardly jibed with what the Record had to say at the time of the 1956 uprising in Budapest; unlike many Communist parties globally, Ariyoshi’s journal was quite critical of the Soviet intervention. Of course, the Left’s focus on global events centered mostly not on Europe but on Asia. A writer who dwarfed the influence exerted by Davis and Ariyoshi said as much. James Michener became an outspoken advocate of statehood in the postwar era, just as his writings about the South Pacific set the tone for a renewed interest in this region and its diversity. He met the Dixiecrats head-on, constructing the isles as a positive symbol of multiracialism that were an alternative to the messiness of Little Rock. As he saw it, statehood would reassure Asians about the racial bona fides of Uncle Sam; further, he saw Hawai‘i as helping to heal his homeland’s nasty racial sores, as mediators between those defined as black and white…‘United States of America and Some Small Specks Far West?’” he asked sarcastically. Reverend Donald J. Ely of Baltimore (p.327) was of like mind. If Hawai‘i were to be crowned a state, then why not “Guam, the Virgin Islands and even South Vietnam”; Oregon was bad enough, he thought, he said, with its “two leftists” in the “Upper Chamber”—“I wish it could be sunk in the South Pacific,” he scoffed. And Hawai‘i would just contribute to this mess, he said, informing Senator J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina that “if everyone would take a firm [stand] against so-called civil rights (actually special privileges for Negroes), as you do, we would not be having the trouble we do today.”107

On March 16, 1962, the Pacific Coast Marine Firemen, Oilers, Watertenders and Wipers Association (MFOW) union called a strike and on April 11, 1962, under the Taft-Hartley Act, a federal injunction was issued to stop the strike. After lengthy court battles, an agreement was reached, with the union gaining numerous concessions, including “overtime in port, pension benefits, wages, vacation, and welfare benefits.

Hawaii was stumbling into statehood at a time when the left-wing press, which could have provided needed clarity to these tumultuous and transformative events, was slipping into remission and the mainstream press was wallowing in a combination of distortion and obliviousness. Not least because of how the ILWU had altered the political economy, Hawaii, as statehood loomed, was enduring significant change that too could have benefited from sharper analysis. The number of registered vehicles doubled in a six-year period following 1947 and accelerated thereafter, and an inevitable outgrowth was more accidents. According to Baer, ‘car wrecks from drunk driving in the early hours of the morning and killing on the highways can be attributed to service men’ for they seemed to think that ‘they can do as they please in this far outpost.’ Land was becoming so expensive in O’ahu – a plaint for some time – that people of modest means were being priced out of the market. The availability of potable water was becoming an unceasing problem – ironically enough in the middle of an ocean. Tourism and nightlife were increasing, turning a sleepy island paradise into something approaching Las Vegas in the Pacific. Baker recalled a time when Honolulu had little in the way of street lighting and no nightclubs, taverns, or cocktail lounges, only ‘saloons’. One of two of them catered to high-class trade, but most of them were frequented by waterfront bums, castaways or perhaps an occasional Hawaiian whose wife was giving him a bad time – but now that moguls like Henry Kaiser were taking an interest in the islands, this was changing. Thus, between 1950 and statehood, tourist spending jumped 350 percent, from 24 million dollars to 109 million annually, while the number of tourists increased from 34,000 in 1945 to 243,000 in 1959. The press baron of Los Aneles, Norman Chandler, was frequenting the islands nowadays, according to Honolulu mogul Lorrin Thurston, who was now enticing J.B. Stoddard. “He has a fabulous oil income” Thurston gushed and was ‘seeking investments ‘ – Hawaii seemed as inviting as anywhere else, it was thought. ..Ariyoshi noticed a proliferation of nude parties on the beaches of paradise.

Yet it seemed that the ILWU had to reassure the doubting who feared that admitting Hawai‘i into the sacrosanct Union would be akin to giving the Kremlin the keys to the federal car—and the way to provide such reassurance was to make concessions as a sign of good faith as the union’s long-pursued goal of statehood loomed ever closer. Opponents of statehood on the mainland, particularly in the former slave South, were in a similar quandary. Rejecting Hawai‘i as a state was viewed widely as a Cold War faux pas, designed to offend Asians, but accepting the archipelago was viewed not only as a gift to the Kremlin, which was thought to dominate Honolulu, but more importantly as an act that would bring two anti–Jim Crow senators to Washington, at a time when massive resistance to desegregation was rising.

The Liberal 1950s? Reinterpreting Postwar American Sexual Culture (Joanne Meyerowitz)

In her 1988 book Homeward Bound, Elaine Tyler May drafted the outline of this now-common interpretation. May borrowed the word “containment” from foreign policy of the Cold War and repositioned it as a broader postwar cultural ethos that applied as well to gender and sexuality. In May’s influential rendition, middle-class Americans saw uncon- trolled sexual behavior as a dangerous source of moral decline that would sap the nation’s strength. In postwar America, she wrote, “fears of sexual chaos” made “non-marital sexual behavior in all its forms . . . a national obsession.” Various officials, experts, and commentators “believed wholeheartedly,” she claimed, in “a direct connection between communism and sexual depravity.” Accordingly, they attempted to police sexual expression and “contain” it within marriage.1 Over the past two decades, other historians have followed May’s lead, elaborat- ing on the Cold War “containment” of sexuality and suggesting its impact on policy, politics, citizenship, masculinity, femininity, and sexual behavior. And yet they have simultaneously undermined the “containment” thesis. As they expanded their base of evidence, they stretched the dominant interpretation and poked a passel of holes—sometimes inadvertently—in the story it tells.

Mounting historical evidence now suggests that the postwar years were not as conservative as sometimes stated. In 1988, the same year that May published Homeward Bound, for example, John D’Emilio and Estelle Freedman presented a somewhat different argument. In Intimate Matters, they accepted the sexual conservatism of postwar American culture but also posed the postwar years as a time of “sexual liberalism.” For D’Emilio and Freedman, sexual liberalism involved “contradictory patterns of expression and constraints.” It “celebrated the erotic, but tried to keep it within a het- erosexual framework of long-term monogamous relationships.” With this formulation of moderate liberalism, they pointed to limited change dur- ing a conservative era. Since the publication of May’s and D’Emilio and Freedman’s books, other historians have made more direct assaults on the notion of postwar sexual “containment.” In her 1999 book, Sex in the Heartland, Beth Bailey wrote of an increasingly “sexualized national cul- ture” in the postwar years, with a rumbling “dissonance” between “public norms and . . . private acts.” In colleges, she found, young adults engaged in “widespread covert violation” of conservative sexual norms, and college offi- cials retreated from earlier policies that aimed to enforce sexual abstinence.

Just as World War I introduced Americans to Europe, making an indelible impression on thousands of farmboys who were changed forever “after they saw Paree,” so World War II was the beginning of America’s encounter with the East – an encounter whose effects are still being felt and absorbed. No single place was more symbolic of this initial encounter than Hawaii, the target of the first unforgettable Japanese attack on American forces, and, as the forward base and staging area for all military operations in the Pacific, the “first strange place” for close to a million soldiers, sailors, and marines on their way to the horrors of war. But as Beth Bailey and David Farber show in this evocative and timely book, Hawaii was also the first strange place on another kind of journey, toward the new American society that began to emerge in the postwar era. Unlike the largely rigid and static social order of prewar America, this was to be a highly mobile and volatile society of mixed racial and cultural influences, one above all in which women and minorities would increasingly demand and receive equal status. With consummate skill and sensitivity, Bailey and Farber show how these unprecedented changes were tested and explored in the highly charged environment of wartime Hawaii. Most of the hundreds of thousands of men and women whom war brought to Hawaii were expecting a Hollywood image of “paradise.” What they found instead was vastly different: a complex crucible in which radically diverse elements – social, racial, sexual – were mingled and transmuted in the heat and strain of war. Drawing on the rich and largely untapped reservoir of documents, diaries, memoirs, and interviews with men and women who were there, the authors vividly recreate the dense, lush, atmosphere of wartime Hawaii – an atmosphere that combined the familiar and exotic in a mixture that prefigured the special strangeness of American society today.

The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority (Ellen D. Wu, 2014)

The Second World War irrevocably altered the place of the United States in the global arena. American history, of course, had never been free of foreign entanglements despite the isolationist streak firmly embedded in the nation’s political culture. Continental expansion, the dispossession of Native peoples, the claim to the Western Hemisphere as its sphere of influence with the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, the annexation of Hawai‘i, and the conquest of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam as spoils of the Spanish-American War in 1898 were all building blocks of US empire. Yet the United States had remained relegated to the second tier of the international pecking order dominated by the European powers before the 1940s. It was not until its anointment as one of “Big Three” Allies that the United States came to be considered—and accepted its responsibilities—as the preeminent world leader. And it was also at this moment that the Asia Pacific region vaulted into a vital geopolitical preoccupation for US officialdom.1

These momentous shifts in the United States’ international position and its foreign policy priorities undergirded an overhaul of the nation’s racial alignments. In the American West and Hawai‘i since the mid-nineteenth century, the various immigrant streams from Asia had been racialized together as the “yellow peril”—an alien menace courted for its labor yet despised for its purportedly unbridgeable cultural distance from white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. With the nation’s entry into World War II, however, the conflation of separate ethnic groups as Orientals lost its political purchase. Most saliently, the battles in the Pacific theater forced the disaggregation of Japanese and Chinese American racialization and social standing; the two could no longer be lumped together into one undifferentiated horde. In the wake of the Pearl Harbor bombing, middlebrow magazines famously published tutorials on “How to Tell Your Friends from the Japs.”

In one direction, World War II saw the culmination of the Asiatic Exclusion regime with the removal and incarceration of 120,000 Pacific coast Nikkei (individuals of Japanese ancestry), two-thirds of whoo were US citizens, and half of who were children under age eighteen. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ostensibly race-neutral Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, authorized the secretary of war to “prescribe military areas … from which any or all persons may be excluded.” The mandate was selectively applied to Japanese Americans in Washington, Oregon, and California—a decision justified by federal authorities on the unsubstantiated grounds that all Japanese Americans were potential fifth columnists by virtue of blood alone. Beginning on March 31, Issei, Nisei, and Sansei (first-, second-, and third-generation immigrants, respectively) left their homes, farms, “businesses, and communities for sixteen temporary “assembly centers.” By November 1, all had moved again, this time to ten long-term “relocation centers,” or concentration camps, in remote locations from Idaho to Arizona to Arkansas. The US Supreme Court upheld the legality of evacuation and detention for the sake of “military necessity” in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), Yasui v. United States (1943), and Korematsu v. United States (1944). In authorizing, executing, and defending the constitutionality of mass imprisonment, the state effectively classified each and every ethnic Japanese in the United States as “enemy aliens,” thereby meriting the utmost instantiation of political and social ostracization.3”

“Besides market share and electoral pull, Leong pitched the significance of Chinese America and the Chinese News at the high-stakes level of international relations. He donated five hundred copies of the Chinese News, for instance, to the China Club of Seattle, a staunch advocate of Sino-American amity, undoubtedly in hopes of attracting subscribers, yet also to show “Chinese-American enterprise in the field of reflecting the problems, progress, and opinions of the Chinese-Americans, a small but important group in the overall field of Chinese-American relations.”102 This was the point in the March 1953 editorial favoring the admission of Hawai‘i to statehood. The entrance of the majority Asian-populated territory to the Union would likely result in the election of Chinese Americans to the US Senate and House of Representatives, the Chinese News conjectured. Diplomatically, the payoff would be huge: “In this uncertain unpeaceful [sic] era of the Pacific cycle in American global growth, Congress can skilfull [sic] use the opinions and backgrounds of any qualified American of Asian ancestry in U.S. foreign policy.”103 Leong forwarded the piece to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, alerting him to the “potential value of the Asian-American” for foreign affairs, adding, “We hope that our editorial comments may be of some service to you in your program and as a magazine dedicated to public service we shall be happy to … furnish you any other type of data relating to the over-all question.”104 This was his 1950s’ rebuttal to the decades-old question “Does My Future Lie in China or America?” in which the rendering “of Chinese Americans as valuable transoceanic intermediaries would be a boon for their citizenship aspirations, America’s Cold War objectives, magazine sales, and Leong’s own professional cachet—a win-win-win-win situation.”

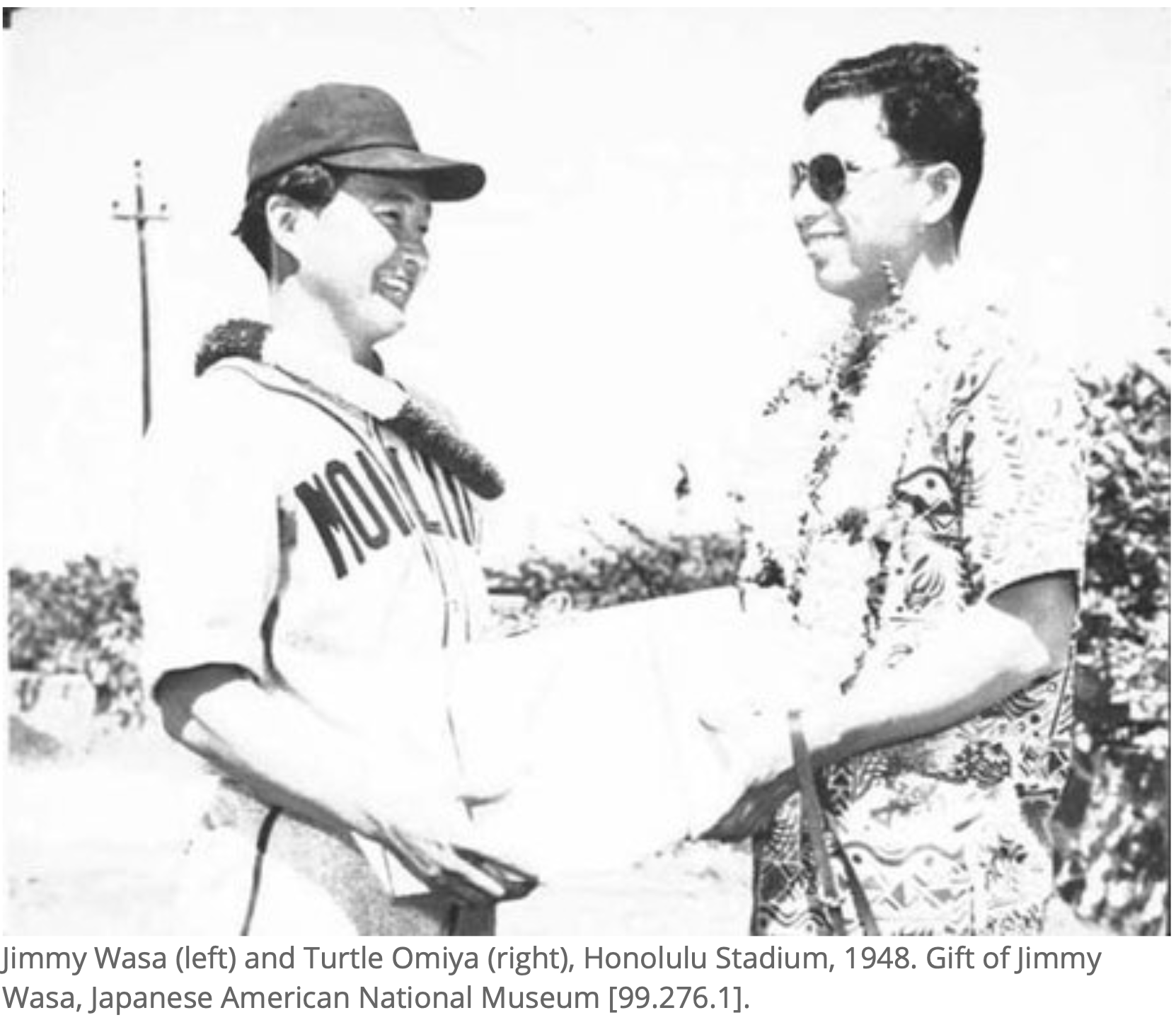

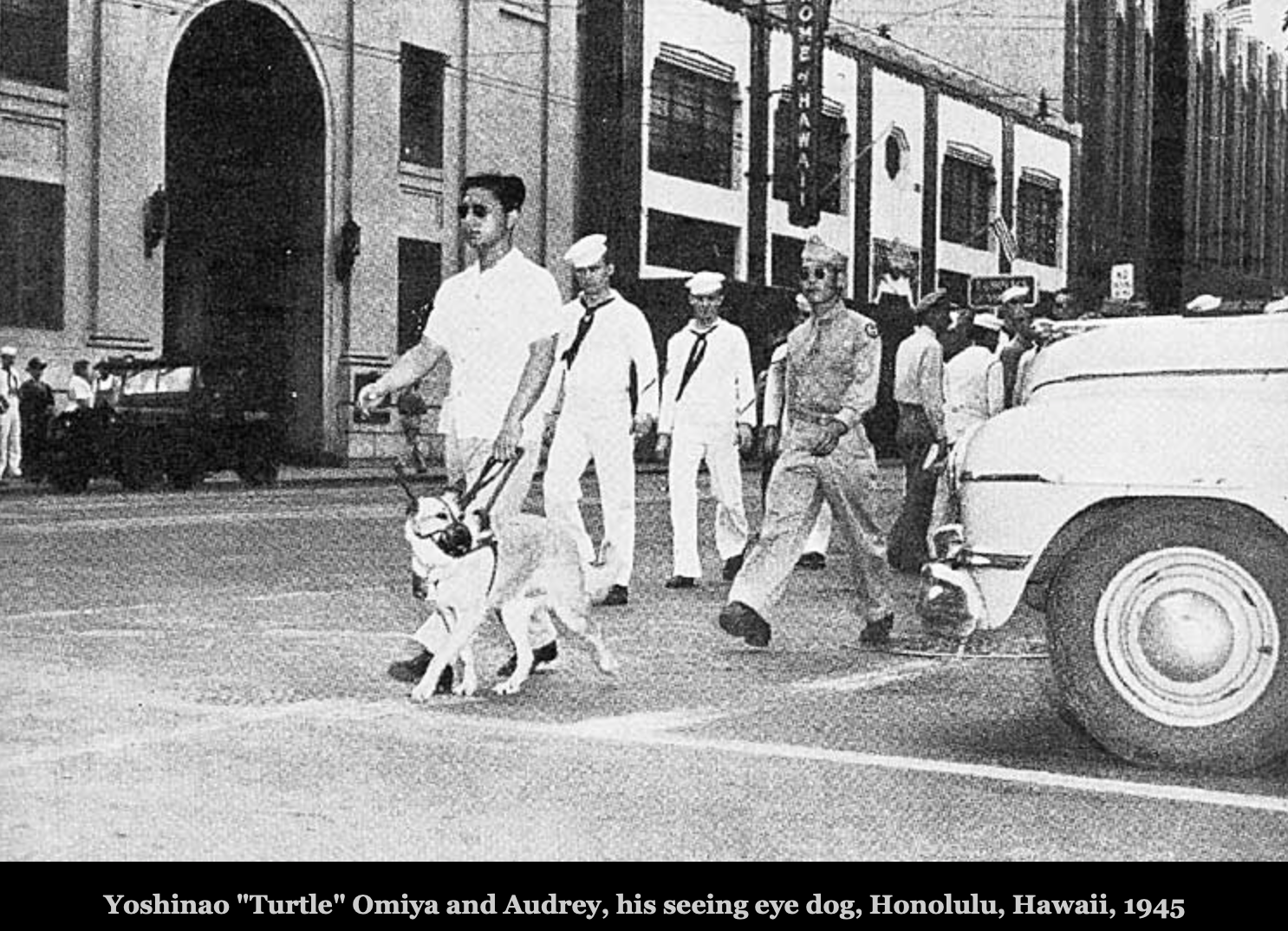

On witnessing the commendable showing on the European front by the Hawaiian-Nisei men of the 100th Battalion (who had begun active duty in August 1943), the military deliberated whether or not to conscript additional Nisei. After a protracted debate, the War Department announced the reinstatement of selective service for Japanese Americans in January 1944; draftees would serve as replacements for the 442nd.28” “Scores of photographs displayed “American soldiers with Japanese faces”—including the famous Kuroki—in the field, at rest, and on leave. Besides the 442nd and 100th, the publication also featured Japanese Americans serving in the Marines, Coast Guard, and Women’s Army Corps, and snippets of articles from newspapers and magazines around the country praising enlisted Nisei.37 The mainstream media proved amenable to this campaign. Just days after the military announced that it would begin to draft Nisei, Life featured “American hero” Yoshinao “Turtle” Omiya, a Hawai‘i-born veteran blinded in combat. The same week, both the Los Angeles Times and Time ran celebratory profiles of Kuroki, stressing his Americanism. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) magazine, Crisis, editorialized that “our fellow citizens of Japanese ancestry … deserve every line” of this publicity, lamenting only that African American soldiers were not receiving the same type of favorable reporting. These depictions suggest that the liberal notion of accepting Japanese Americans as members of the national community had started to gain a toehold among white and black Americans during the latter part of the war.”

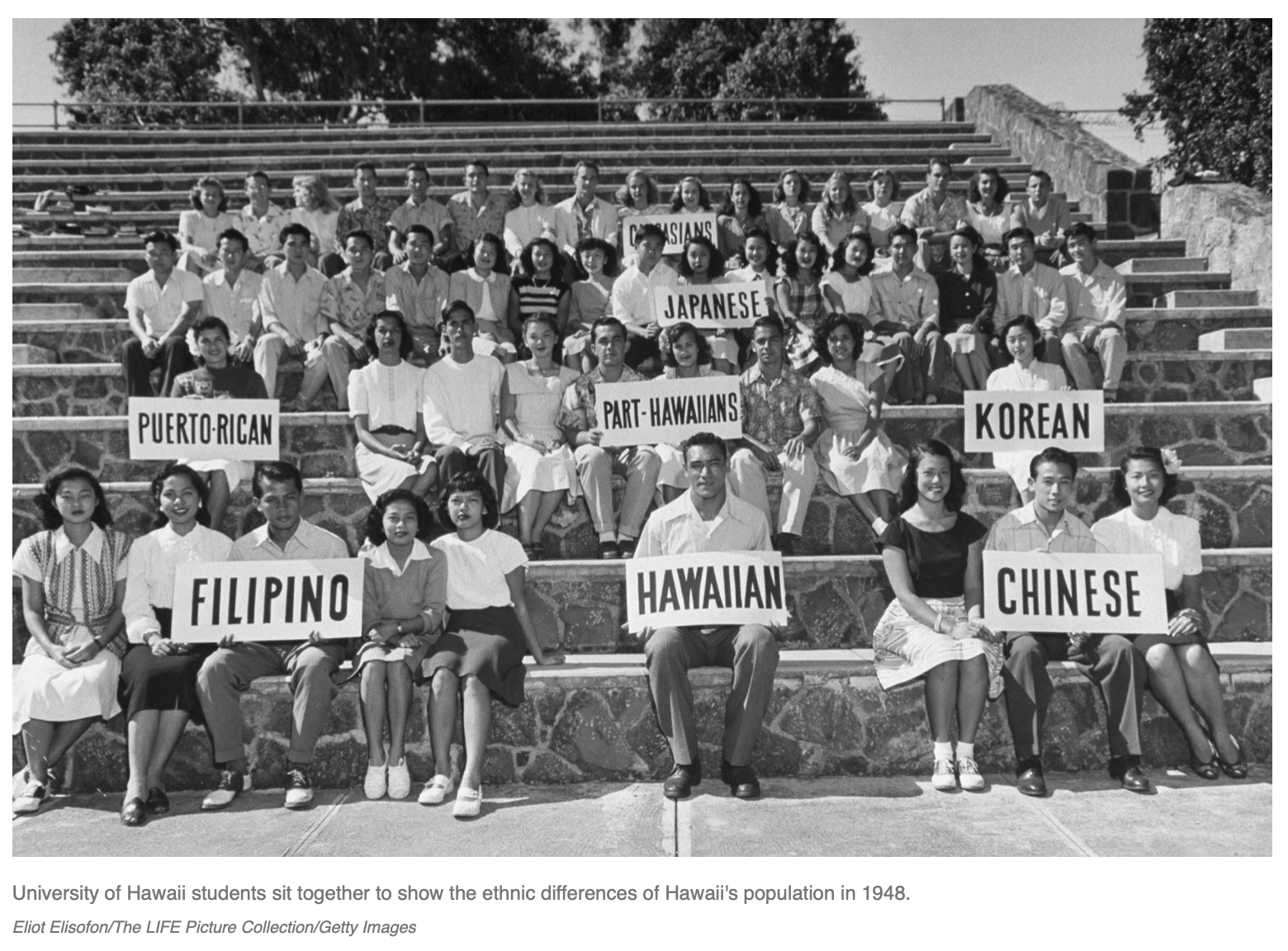

“Nisei delegates successfully swayed their colleagues to incorporate Japanese American–specific planks into the platform: immediate statehood for Hawai‘i, blanket compensation for internees’ losses moving beyond the limitations of the JACL-backed Evacuation Claims Law, and the right to naturalization for Issei.” Americans have long been enamored with Hawai‘i as paradise: lush flora and fauna, dreamy topography, and temperate clime. Beyond these natural splendors, Yankee fantasies have also latched on to the exoticism of the islands’ people and their putative culture, especially the notion of a welcoming, feminized, and sexually available aloha spirit. This imagination has operated to justify the United States’ continued domination of the archipelago since the mid-nineteenth century.1 By the early twentieth century, this fascination had come to encompass the idea of Hawai‘i as a racial paradise.2 In the 1920s and 1930s, intellectuals began to tout the islands’ ethnically diverse composition—including the indigenous population, white settler colonists, and imported labor from Asia and other locales—as a Pacific melting pot free of the mainland’s social taboos on intermingling.”

After World War II, the association of Hawai‘i with racial harmony and tolerance received unprecedented national attention as Americans heatedly debated the question of whether or not the territory, annexed to the United States in 1898, should become a state. Statehood enthusiasts tagged the islands’ majority Asian population, with its demonstrated capability of assimilation, as a forceful rationale for admission. Americans everywhere heralded Hawai‘i as a model for race relations as well as a valuable meeting ground between East and West. With the Cold War in full swing, sketching the territory as proof of American multiracial “democracy at work” and a vital link to Asia proved to be a winning strategy. Hawai‘i became the fiftieth state on August 21, 1959.”

Hawai‘i’s bid for statehood occupies a central place in the story of the origins of the model minority, paralleling and reinforcing critical changes in the racialization of continental Asian Americans. Like the postinternment reconstruction of Nikkei as heroic soldiers and “Quiet Americans” along with the far-flung praise for Chinatown’s exemplary families and nondelinquent children, the statehood campaign was one of the most high-profile sites for remaking the image of Asian Americans after World War II, capturing the interest of countless individuals in the arenas of formal politics and mass culture.3 Given that Americans conceived of Hawai‘i as a distinctly “Eastern” space in the 1940s and 1950s, the statehood question served as a national referendum on the problem of post-Exclusion Asiatic race and citizenship—a symbolic proxy for Asian Americans’ place in the nation. Through admission coupled with the sending of ethnic Japanese and Chinese representatives from the state of Hawai‘i to the US Congress, Americans came to regard people of Asian ancestry as model minorities. Statehood, in short, emblematized the nation’s investment in the emergent paradigm.”

Until World War II, many—if not most—Americans could not fathom Hawai‘i’s entry into the Union, given its physical distance from the continent, its sizable Asian presence, and the struggle between the United States and Japan for domination in the Pacific. But with Hawai‘i’s importance as a battleground during the war and new diplomatic imperatives after 1945, Cold War liberals repitched the islands’ Oriental Problem as a geopolitical asset. That the vast majority of the US population approved of statehood by the late 1940s and early 1950s suggests that many people accepted the logic of racial liberalism and were willing to reposition the boundaries of the national community to include persons of Asian ancestry. While contemporaries celebrated Hawai‘i’s admission as the moment elevating “Oriental citizens” to “full equality,” this act of inclusion generated its own constellation of racial exclusions affecting Native Hawaiians, African Americans, and Asian Americans themselves. As with the concurrent processes of transmuting Asian Americans into model minorities on the mainland, statehood was both a solution to the conundrum of reconfiguring the nation’s racial order in the mid-twentieth century and a seed for new dilemmas of racial management that would plague the nation in the post–civil rights era.

Hawai‘i’s Oriental Problem

Hawai‘i’s racial makeup precluded any real possibility of statehood before the 1940s. White planters had little interest in altering the territorial status that enabled them to horde the islands’ wealth and power. The oligarchy and its mainland allies regarded Hawai‘i’s Asiatics as a menace on several fronts: economic, social, political, and military. In myriad ways, whites’ construction of Hawai‘i’s Oriental Problem mirrored anti-Asian animus in the US West. Opposition to statehood therefore can be understood as a facet of the Asiatic Exclusion regime spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” The roots of Hawai‘i’s Oriental Problem lay in the Māhele—literally, “division”—of 1848, the revolutionary privatization and redistribution of land masterminded by New England missionary-merchants (or haole in local terminology). At the expense of indigenous peoples, the haole elite acquired substantial tracts that it aimed to transform into industrial sugar plantations. But doing so required cheap and plentiful labor. The rapid decimation of the native population since the introduction of Western diseases in the late eighteenth century and intractability of those who survived obliged growers to look offshore for workers. Consequently, from the 1850s through the 1930s, plantation owners recruited over four hundred thousand laborers to the islands, mainly from China, Japan, and the Philippines, with smaller numbers from Portugal, Korea, Puerto Rico, Norway, Russia, Germany, Spain, and various Pacific islands.4

Whites and Native Hawaiians felt ambivalent about the influx of Far Eastern workers. Asiatic immigration, of course, had made possible the large-scale cultivation of sugar. The independent Hawaiian kingdom had actually encouraged labor recruitment, hoping that an uptick in the Asian population would offset haole domination. Nonetheless, haole and some natives expressed apprehension of an Oriental invasion, leading the Kingdom to pass its own apprehension of an Oriental invasion, leading the Kingdom to pass its own version of US Chinese Exclusion laws in 1886. This hostility extended to the exploding Japanese population, brought in as a replacement labor force. Anti-Asian antagonism by the late 1890s infused the annexation deliberations. Americans who desired the formal colonization of the islands by the United States warned of the “danger of Asiatic ascendancy” and urged their compatriots to preempt a takeover by Japan. Annexation’s detractors concurred that the islands were disturbingly Orientalized, but drew the opposite conclusion: that the yellow peril necessitated that the United States abandon its imperialist designs, lest Hawai‘i seek statehood in the future.”

Anti-Japanese acrimony in Hawai‘i reached its terrible crescendo after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. On the evening of December 7, 1941, the army imposed martial law on the entire territory. Japanese Americans bore the brunt of this rule, subjected to unparalleled levels of surveillance and restrictions on working and everyday living. For their part, Japanese Americans sought to convince their fellow islanders of their exclusive loyalty to the United States by participating in the war mobilization, sponsoring the Speak American Campaign, and jettisoning all personal displays of Japanese culture. None of this, however, was enough to reverse the military’s orders to close Nikkei institutions and incarcerate nearly fifteen hundred Japanese American elders. Hence, at the outset of World War II, the prognosis for statehood seemed highly improbable.11

Hawai‘i’s Unorthodox Race Doctrine

Although Hawai‘i’s Oriental Problem commandingly structured haole-Asian relations in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, it was never all pervasive. From the 1920s onward, religious leaders, intellectuals, and social commentators furnished a competing discourse by touting the islands as variously a racial frontier, racial laboratory, and racial paradise where the Asiatic presence was innocuous, if not beneficial. Their diagnoses established the liberal position on race in Hawai‘i—a standpoint that would prove critical to the admission argument after World War II. The beginnings of this alternate framework can be traced to white American missionaries who feared that domestic discord on the Pacific coast negatively impacted their overseas conversion attempts. Consequently, they attempted to disprove popular beliefs that “Orientals” were incapable of assimilating to American life—the ideological core of anti-Asian xenophobia. To do so, they enlisted the expertise of social scientists, including Robert E. Park of the University of Chicago, author of the influential “interaction cycle” Theory—positing competition, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation as the four stages of encounter between two groups—to understand why Asians had been unable to move beyond the conflict stage.12”

To answer this question, elite thinkers looked to Hawai‘i, “the one place where [racial] injustice does not glare.” Its seeming tranquillity despite its diversity, especially its usually high rates of interracial marriage, suggested the possibility of intercultural accord everywhere. Intellectuals perceived the islands as “the ultimate racial laboratory,” where the end stage of the race relations cycle (assimilation) had already been reached. Chicago School sociologists and their scholarly descendants—especially the University of Hawai‘i’s sociology department—soon developed a preoccupation with Hawai‘i’s unique culture of intermingling. Led by University of Hawai‘i professor Romanzo Adams, social scientists upheld the romance of the islands as racially enlightened, in spite of the haole-planter ruling class. Adams attributed the origins of the “unorthodox” “doctrine” to the native Hawaiian ethos of aloha (reciprocal love and generosity) and willingness of Anglo-American settlers to abide by such a code.13

In advancing the racial equality thesis, social scientists posited a radical departure from exclusionists’ claim that Orientals were funda“mentally incompatible with American culture and democracy. They assumed that Asiatic assimilation was both the normative and inevitable outcome of contact between Asians, Hawaiians, and whites in the crucible of Hawaiian society. Their research proved that Asian islanders had embraced “occidental culture,” as indexed by growing numbers of voters and middle-class professionals, an increase in residential dispersion, and rising rates of intermarriage. As one concluded, “They are oriental in appearance, but not in reality.”14”

“Intellectuals’ advocacy efforts mirrored an analogous focus in the popular press. Akin to the social scientists, journalists and commentators depicted Hawai‘i as a racial paradise that fostered a culture of assimilation characterized by the commonplace of interracial marriage and mixed-race peoples. The ethnic and religious conflicts of the 1930s and World War II provided fertile ground for this idea to flourish. In June 1942, Life magazine featured a pictorial of individual women representing Hawai‘i’s various racial “combinations,” such as Filipino Chinese, Hawaiian white, and Hindu Dane, meant to depict Hawai‘i as a “melting pot bubbling comfortably to produce a fine healthy stew.” The photo spread was based on the research of Swedish race biologist William W. Krauss, who located in Hawai‘i “an atmosphere of interracial peace and harmony.” In recounting his findings, Life joined the growing chorus proposing that Hawai‘i’s amicable relations be upheld as “a striking object lesson in racial accommodation” for other nations beset with strife.16”