Sphera

Nuclear bomb exploded over the Pacific

Two Lines Converging

The old fault lines of geopolitics have become unstable again. Both Russian and Chinese military vessels and aircraft are now frequently engaged in near misses and close confrontations with those of the United States and its allies. Allegations of nuclear missile launches, even if involving only unarmed missiles, remind us that nuclear and conventional weapons treaties that took a generation to negotiate can be violated or obliterated in the 2 to 60 minutes it takes an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) to reach its target.” GEOPOLITICS AS THE FRICTION BETWEEN TWO JETS, GEOPOLITICS AS VELOCITY… Pippa malmgren… Disappearance is also our future. . . . From now on power is in disappearance: under the sea with nuclear submarines, in the air with U-2’s, spy-planes, or still higher with satellites and the space shuttle, in its first military voyage-voyage from North to South, but also from Zenith to Nadir.

But is it actually a bomb? perhaps it knocks out the satellites, in a Kessler feedback, that leads to jutted international talks… or is it an information bomb, is it a grand inquisitor, an idea, Pacific in its resonance

So it’s not the power of the explosion itself but the media explosion that matters.Yes. You might say that during the period of deterrence the media developed because actual nuclear blasts had been frozen and delivery systems, further enhanced by means of the satellite, guidance systems and smart technology’s pinpointing targets, so the capacity to gather information in real time had no limits. Today therefore, the end of deterrence corresponds to the beginning of the information war, a conflict where the superiority of information is more important than the capability to inflict damage. This is an entirely new situation. We’re entering a third age of military weaponry.

Rashomonic. An exchange of points of view is what Cubism and earlier Soviet cinematography (Shub, Vertov, Eisenstein, et al.) proposed in their experiments at the dawn of the twentieth century. The representation of objects and situations from many angles, on the same canvas or in a film scene, introduced the elements of time passing, which became a fundamental element of our age: the (often controversial) principle of simultaneity, which goes beyond its time-element.

Sphera existed in the lunar/solar dyad, Londongrad alternating between blue and red sun

We are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War (lunar) / Solar dyads

The Ocean Dyad itself is telluric, pulsing, Solarian:

“I got up. The disc of the sun, reminiscent of a hydrogen explosion, was sinking into the ocean, and as I descended the stairway I was pierced by a jet of horizontal rays which was almost tangible.”

“In the meantime, the scientists had split into two opposing camps; the bone of contention was the ocean. On the basis of the analyses, it had been accepted that the ocean was an organic formation (at that time, no one had yet dared to call it living). But, while the biologists considered it as a primitive formation—a sort of gigantic entity, a fluid cell, unique and monstrous (which they called ‘prebiological’), surrounding the globe with a colloidal envelope several miles thick in places—the astronomers and physicists asserted that it must be an organic structure, extraordinarily evolved. According to them, the ocean possibly exceeded terrestrial organic structures in complexity, since it was capable of exerting an active influence on the planet’s orbital path. Certainly, no other factor could be found that might explain the behavior of Solaris; moreover, the planeto-physicists had established a relationship between certain processes of the plasmic ocean and the local measurements of gravitational pull, which altered according to the ‘matter transformations’ of the ocean. […] Consequently it was the physicists, rather than the biologists, who put forward the paradoxical formulation of a ‘plasmic mechanism’, implying by this a structure, possibly without life as we conceive it, but capable of performing functional activities—on an astronomic scale, it should be emphasized.

It was during this quarrel, whose reverberations soon reached the ears of the most eminent authorities, that the Gamow-Shapely doctrine, unchallenged for eighty years, was shaken for the first time.

There were some who continued to support the Gamow-Shapley contentions, to the effect that the ocean had nothing to do with life, that it was neither ‘parabiological’ nor ‘prebiological’ but a geological formation—of extreme rarity, it is true—with the unique ability to stabilize the orbit of Solaris, despite the variations in the forces of attraction. Le Chatelier’s law was enlisted in support of this argument. […] To challenge this conservative attitude, new hypotheses were advanced—of which Civito-Vitta’s was one of the most elaborate—proclaiming that the ocean was the product of a dialectical development: on the basis of its earliest pre-oceanic form, a solution of slow-reacting chemical elements, and by the force of circumstances (the threat to its existence from the changes of orbit), it had reached in a single bound the stage of ‘homeostatic ocean,’ without passing through all the stages of terrestrial evolution, by-passing the unicellular and multicellular phases, the vegetable and the animal, the development of a nervous and cerebral system. In other words, unlike terrestrial organisms, it had not taken hundreds of millions of years to adapt itself to its environment—culminating in the first representatives of a species endowed with reason—but dominated its environment immediately. The first attempts at contact were by means of specially designed electronic apparatus. The ocean itself took an active part in these operations by remodelling the instruments. All this, however, remained somewhat obscure. What exactly did the ocean’s ‘participation’ consist of? It modified certain elements in the submerged instruments, as a result of which the normal discharge frequency was completely disrupted and the recording instruments registered a profusion of signals—fragmentary indications of some outlandish activity, which in fact defeated all attempts at analysis. Did these data point to a momentary condition of stimulation, or to regular impulses correlated with the gigantic structures which the ocean was in the process of creating elsewhere, at the antipodes of the region under investigation? Had the electronic apparatus recorded the cryptic manifestation of the ocean’s ancient secrets? Had it revealed its innermost workings to us? Who could tell? No two reactions to the stimuli were the same. Sometimes the instruments almost exploded under the violence of the impulses, sometimes there was total silence; it was impossible to obtain a repetition of any previously observed phenomenon. Constantly, it seemed, the experts were on the brink of deciphering the ever-growing mass of information. Was it not, after all, with this object in mind that computers had been built of virtually limitless capacity, such as no previous problem had ever demanded?” “And, indeed, some results were obtained. The ocean as a source of electric and magnetic impulses and of gravitation expressed itself in a more or less mathematical language. Also, by calling on the most abstruse branches of statistical analysis, it was possible to classify certain frequencies in the discharges of current. Structural homologues were discovered, not unlike those already observed by physicists in that sector of science which deals with the reciprocal interaction of energy and matter, elements and compounds, the finite and the infinite. This correspondence convinced the scientists that they were confronted with a monstrous entity endowed with reason, a protoplasmic ocean-brain enveloping the entire planet and idling its time away in extravagant theoretical cognitation about the nature of the universe. Our instruments had intercepted minute random fragments of a prodigious and everlasting monologue unfolding in the depths of this colossal brain, which was inevitably beyond our understanding. Forty-eight hours later, a beam of X-rays modulated by my own brain-patterns was bombarding the almost motionless surface of the ocean at regular intervals. At the end of this two-day journey we had reached the outskirts of the polar region. The disc of the blue sun was setting to one side of the horizon, while on the opposite side billowing purple clouds announced the dawn of the red sun. In the sky, blinding flames and showers of green sparks clashed with the dull purple glow. Even the ocean participated in the battle between the two stars, here glittering with mercurial flashes, there with crimson reflections. The smallest cloud passing overhead brightened the shining foam on the wave-crests with iridescence. The blue sun had barely set when, at the meeting of ocean and sky, indistinct and drowned in blood-red mist (but signalled immediately by the detectors), a symmetriad blossomed like a gigantic crystal flower.

And the Central Character is Virilian/Slothrop-paranoiac/Vertov-like, stealth flying a U2 plane, or in low earth orbit with Colorado Command… witnessing the moment that the two lines converge… / filled with doubts, leaping between Berlin Wall in his head, Oswald-like in that way, switching hemispheres – the ancient subcortical silent runner sub, the conscious flight, the eyeballing, zeroing von karmanal.

You can’t force the people to leave the cities. But if you stress the fact that the Pershings, 55-20’s, missiles, etc., could fall at any moment on the great urban centers, people start thinking seriously of moving to the country. The nuclear threat makes you swallow anything. It’s racket logic! Nuclear blackmail ties in with and reinforces tendencies already active in our society. With the end ofthe age ofproduction, we are seeing the disappearance of the territorial bases of workers’ identity. Technology can now work in fragments, in geographical dispersal, as with the”cottage industries. ” I’m very sensitive to limits, to inter ruptions-interfaces, if you prefer. It’s not by chance that I studied the Atlantic Wall. I didn’t study the blockhouses, I studied their position. I studied the wall, the circle of blockhouses, every thing that happens between the continental space and the maritime space. Later I went to see the Siegfried Line and the Maginot Line, but after the Atlantic Wall: I never would have wanted to go beforehand. It’s because I was interested in the coastal region. For me, the coastal region is an amazing thing, amarvellous interruption, an interface, as they say. I’ve always thought of space in terms of breaks, in terms of either/or, in terms of the dividing line of waters-those places where things are exchanged, transformed. Chronopolitics and the distribution of time-that’s the level I see them on, not on the level of expanse. Expanse is less important than the point at which things change, at which there is a fragment. Why do dividing lines interestyou? Because they multiply the fragments, they multiply the interfaces, they multiply what is not neutral. The continent and the sea exist thanks to the coastal area. And that’s a very interesting ambiva lence. So I prefer not to describe the situation we’re discussing as “tragic,” “paranoid,” etc. I never use these terms, except for nuclear arms and war.

See also Seveneves (Neal Stephenson, 2015):

THE MOON BLEW UP WITHOUT WARNING AND FOR NO APPARENT reason. It was waxing, only one day short of full. The time was 05:03:12 UTC. Later it would be designated A+0.0.0, or simply Zero. An amateur astronomer in Utah was the first person on Earth to realize that something unusual was happening. Moments earlier, he had noticed a blur flourishing in the vicinity of the Reiner Gamma formation, near the moon’s equator. He assumed it was a dust cloud thrown up by a meteor strike. He pulled out his phone and blogged the event, moving his stiff thumbs (for he was high on a mountain and the air was as cold as it was clear) as fast as he could to secure the claim to himself. Other astronomers would soon be pointing their telescopes at the same dust cloud—might be doing it already! But—supposing he could move his thumbs fast enough—he would be the first to point it out. The fame would be his; if the meteorite left behind a visible crater, perhaps it would even bear his name. His name was forgotten. By the time he had gotten his phone out of his pocket, his crater no longer existed. Nor did the moon. When he pocketed his phone and put his eye back to the eyepiece of his telescope, he let out a curse, since all he saw was a tawny blur. He must have knocked the telescope out of focus. He began to twiddle the focus knob. This didn’t help. Finally he pulled back from the telescope and looked with his naked eyes at the place where the moon was supposed to be. In that moment he ceased to be a scientist, with privileged information, and became no different from millions of other people around the Americas, gaping in awe and astonishment at the most extraordinary thing that humans had ever seen in the sky.

In movies, when a planet blows up, it turns into a fireball and ceases to exist. This is not what happened to the moon. The Agent (as people came to call the mysterious force that did it) released a very large amount of energy, to be sure, but not nearly enough to turn all the moon’s substance into fire. The most generally accepted theory was that the puff of dust observed by the Utah astronomer was caused by an impact. That the Agent, in other words, came from outside the moon, pierced its surface, burrowed deep into its center, and then released its energy. Or that it simply kept on going out the other side, depositing enough energy en route to break up the moon. Another hypothesis stated that the Agent was a device buried in the moon by aliens during primordial times, set to detonate when certain conditions were met. In any case, the result was that, first, the moon was fractured into seven large pieces, as well as innumerable smaller ones. And second, those pieces spread apart, enough to become observable as separate objects—huge rough boulders—but not enough to continue flying apart from one another. The moon’s pieces remained gravitationally bound, a cluster of giant rocks orbiting chaotically about their common center of gravity. That point—formerly the center of the moon, but now an abstraction in space—continued to revolve around the Earth just as it had done for billions of years. So now, when the people of Earth looked up into the night sky at the place where they ought to have seen the moon, they saw instead this slowly tumbling constellation of white boulders. Or at least that is what they saw when the dust cleared. For the first few hours, what had been the moon was just a somewhat-greater-than-moon-sized cloud, which reddened before the dawn and set in the west as the Utah astronomer looked on dumbfounded. Asia looked up all night at a moon-colored blur. Within, bright spots began to stand out as dust particles fell into the nearest heavy pieces. Europe and then America were treated to a clear view of the new state of affairs: seven giant rocks where the moon ought to have been.” BEFORE THE LEADERS OF THE SCIENTIFIC, MILITARY, AND POLITICAL worlds began using the word “Agent” to denote whatever had blown up the moon, that word’s most common interpretation, at least in the minds of the general public, had been in the pulp-fiction, B-movie sense of a secret agent or an FBI agent. Persons of a more technical mind-set might have used it to mean some sort of chemical, such as a cleaning agent. The closest match for how the word would be used forever after was the sense in which it was used by fencers and martial artists. In a sword-fighting drill, where one participant is going to mount an attack and the other is to respond in some way, the attacker is known as the agent and the respondent is known as the patient. The agent acts. The patient is passive. In this case an unknown Agent acted upon the moon. The moon, along with all the humans living in the sublunary realm, was the passive recipient of that action. Much later, humans might rouse themselves to take action and be agents once again. But now and for long into the future they would be nothing more than patients.

STARFISH PRIME, machine shimmering, the Oahan blipland

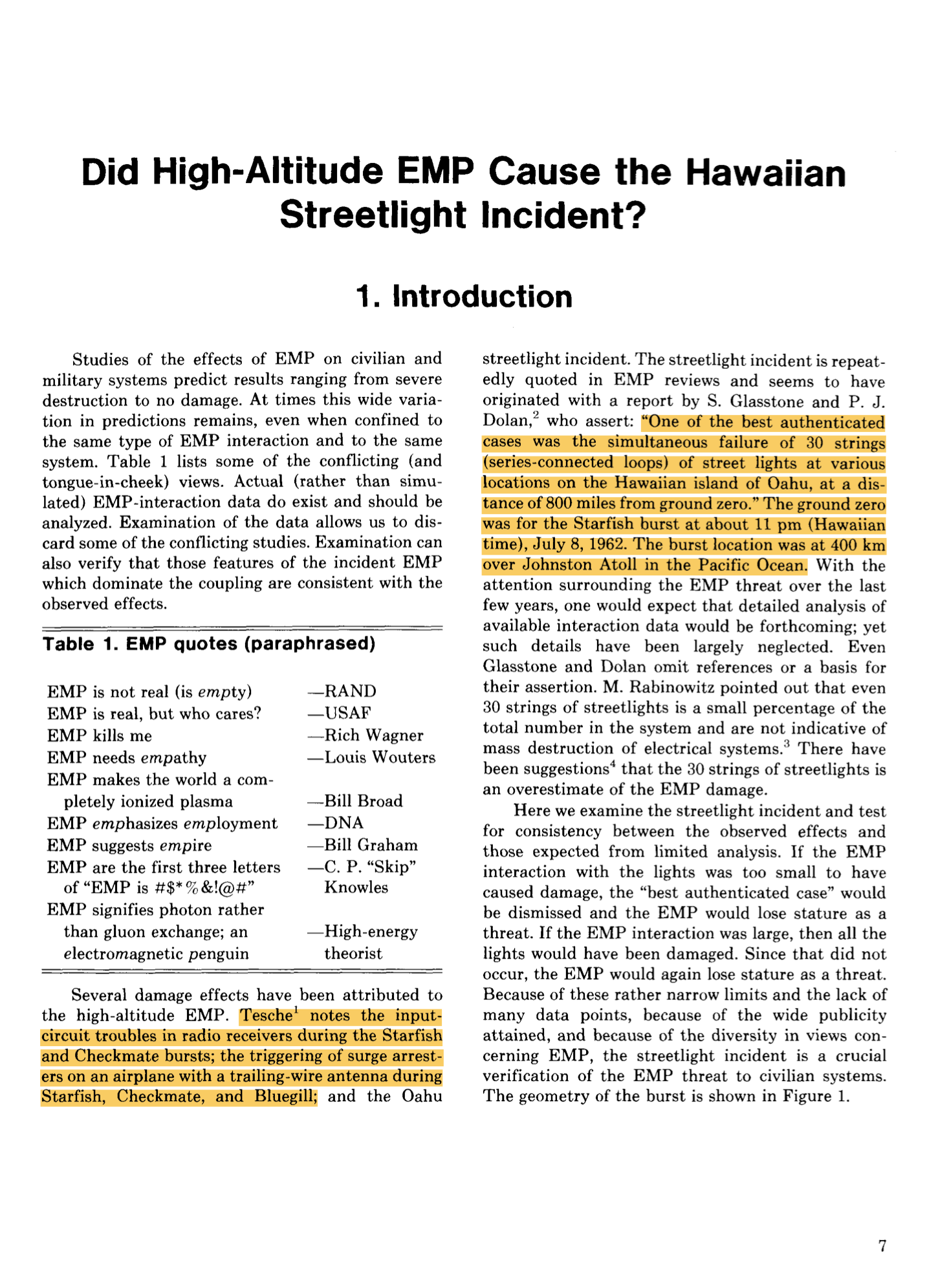

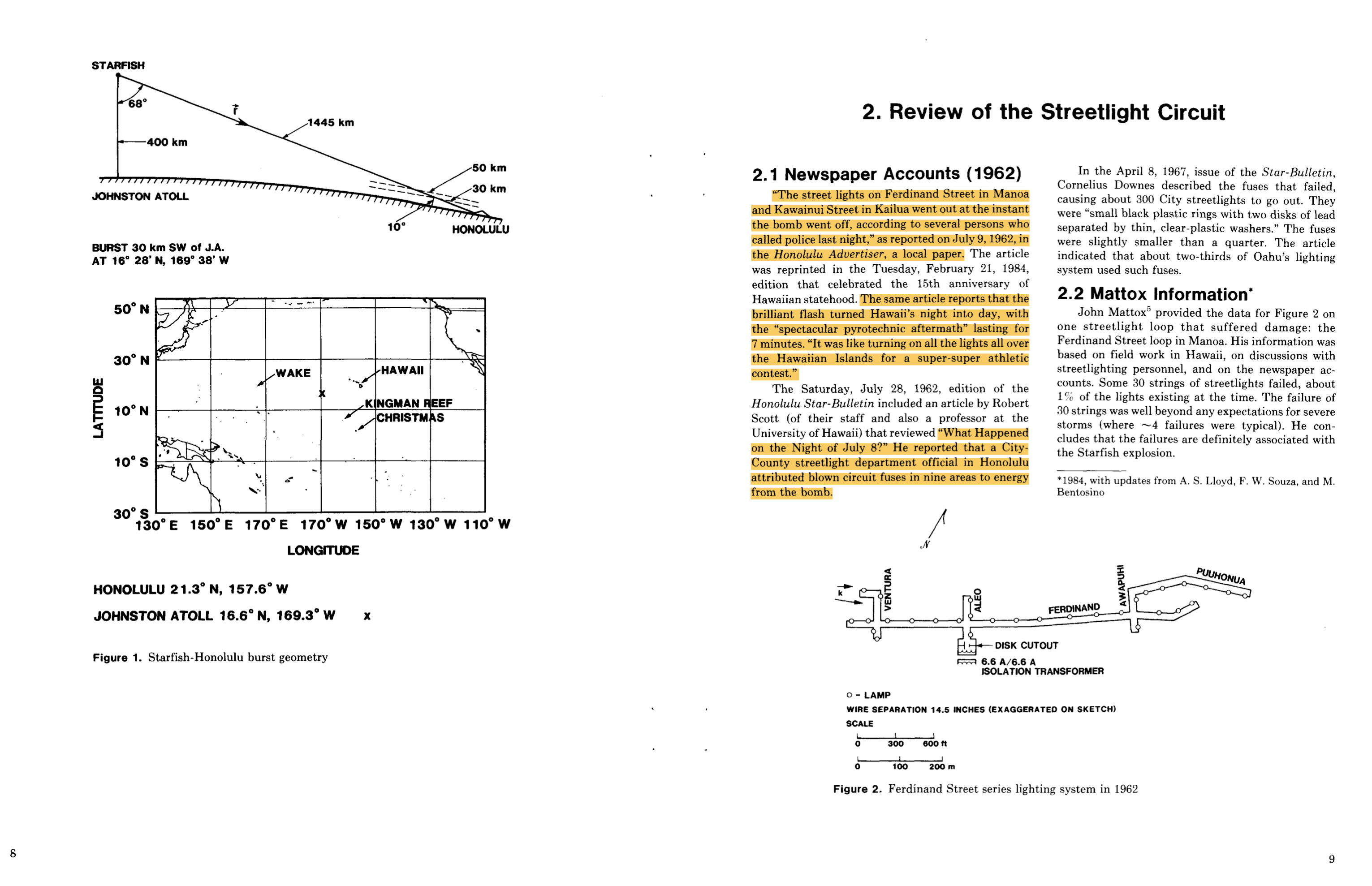

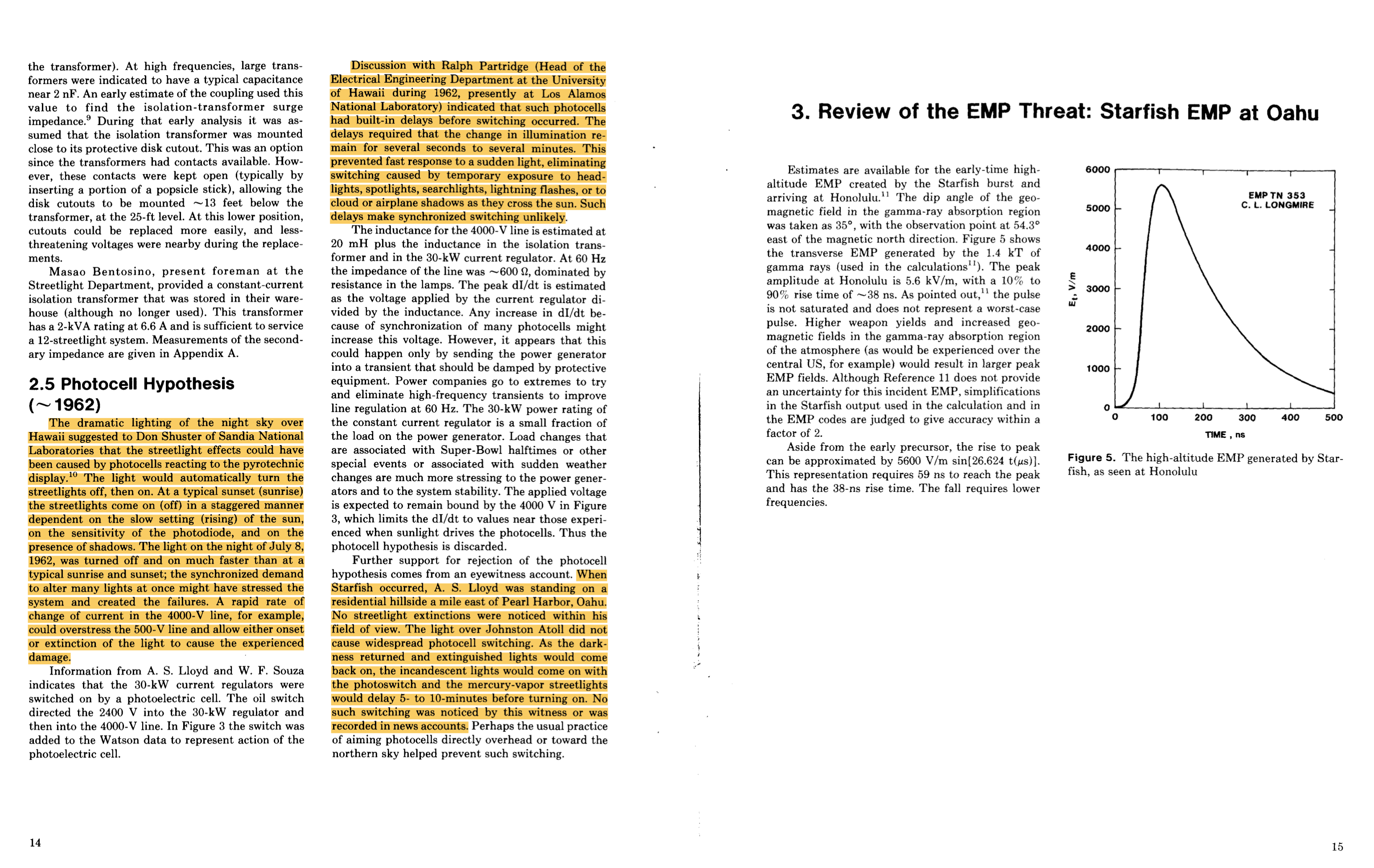

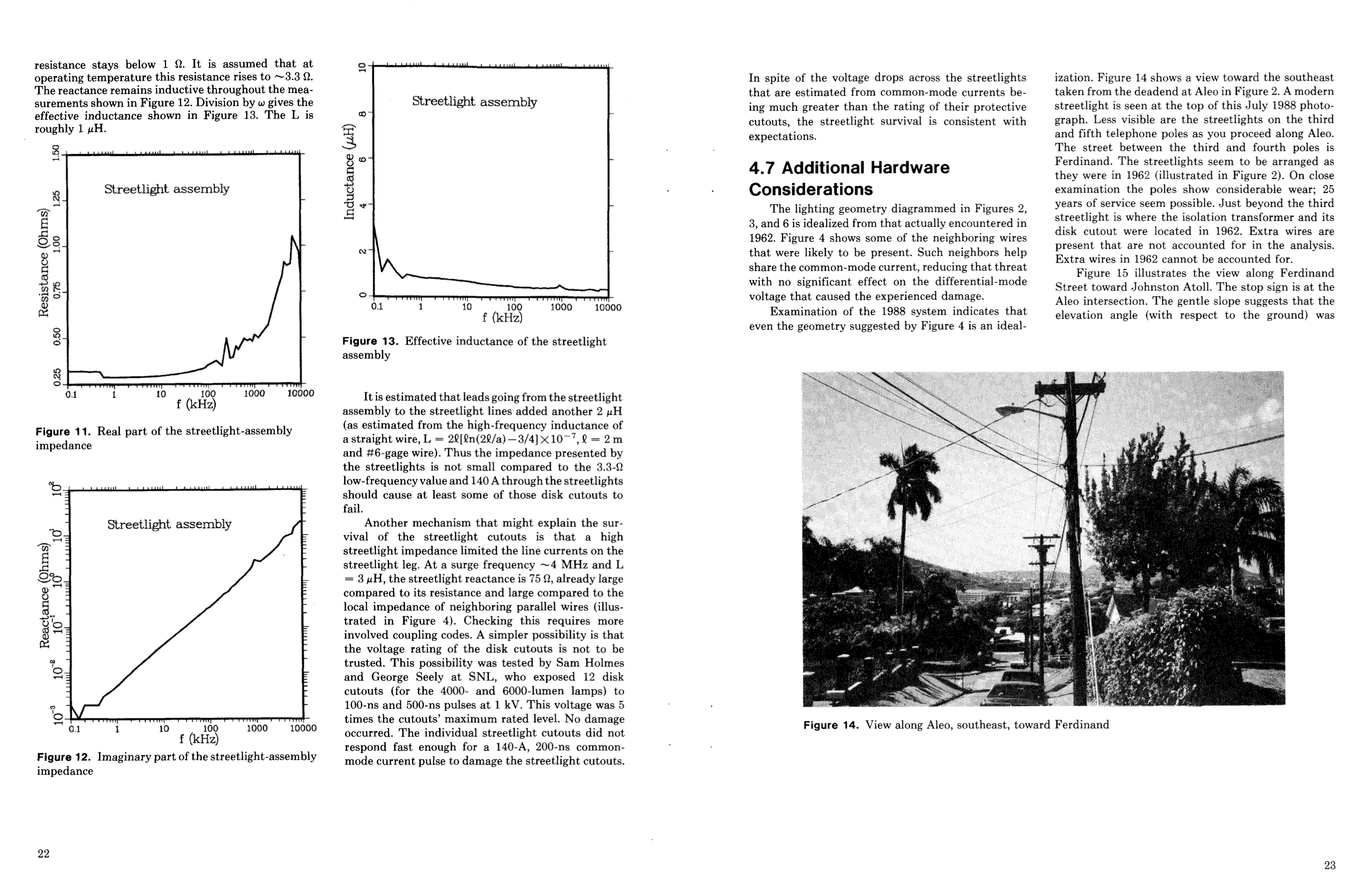

July 8, 1962, a bright new “sun” dawned in the nighttime sky over Hawaii. Briefly resembling the blazing sphere of nuclear fusion that is our bright sun, this fiery burst quickly ballooned to seem as if it would consume the sky itself. It was a thermonuclear blast, 250 miles up, triggered by a 1.4 megaton fusion bomb called Starfish Prime. To date, it remains the largest nuclear test ever conducted in outer space. U.S. government personnel with the Atomic Energy Commission and the Defense Atomic Support Agency carried out the experiment, witnessed by thousands of Americans on the Hawaiian Islands. Though Starfish Prime detonated roughly 900 miles away, the initial spherical explosion could be viewed quite clearly from the ground. The sky then lit up with artificial auroras, a result of some of the 10^29 energetic electrons released from the blast reaching and being absorbed by the atoms and molecules of Earth’s mesophere. These could be seen as far away as New Zealand. For roughly seven minutes, the night was a glorious light show, “like turning on all the lights over the Hawaiian Islands for a super-super athletic contest,” the Honolulu Advertiser reported. Afterwards, the sky gradually dimmed to an eerie glow which persisted for four hours. Starfish Prime’s effects were also felt on the ground. The blast triggered an electromagnetic pulse (EMP), a result of electrons being rapidly accelerated and fleetingly forming their own powerful magnetic field. Citizens reported that almost at the very instant of the blast, radios blacked out, telephones stopped working, and thirty strings of streetlights on the island of Oahu spectacularly failed. Higher up, Starfish Prime’s effects lingered for months. Extra energetic electrons trapped by Earth’s magnetic field formed their own radiation belts which damaged the internal components of various orbiting satellites. At least six were rendered inoperable over time, including Telstar 1, the first satellite to relay television pictures and telephone calls through space. Only a few more nuclear tests in space were performed in the wake of Starfish Prime, and none came remotely close to its daunting power. The Partial Test Ban Treaty would enter into effect the following year, ending all above ground nuclear tests. It’s a good thing we haven’t seen another nuclear test in space since. Subsequent analyses suggest that any detonation in low-Earth orbit would be extremely hazardous to the 1,400+ satellites and six astronauts currently inhabiting in the region. (https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2020/01/14/the_largest_nuclear_test_in_outer_space_had_startling_effects_on_hawaii.html)

0800062 – Starfish Prime Test Interim Report by Commander JTF-8; Fishbowl Auroral Sequences – Silent; Dominic on Fishbowl Phenomenon -Silent; Fishbowl XR Summary – Silent – 1962 – 1:01:25 – Black&White and Color – Four Films on One Video Starfish Prime Test Interim Report by Commander JTF-8 – 7:45 – Sound – STARFISH PRIME, was one of the high-altitude nuclear tests in the Operation Fishbowl series conducted in the Pacific Proving Ground in 1962. It was launched in the Johnston Island area to an altitude of about 400 kilometers by a Thor rocket and had a yield of 1.4 megatons. The test evaluated the capabilities of an antiballistic missile to operate in a nuclear environment and the vulnerability of a U.S. reentry vehicle to survive a nearby nuclear blast. It also provided information on the ability of a U.S. radar system to detect and track reentry vehicles. Another goal was to discern the effects of a high-altitude blast on command and control systems, which were shown to be vulnerable in earlier high-altitude tests. The final goal was to obtain information on the feasibility of testing in outer space. Fishbowl Auroral Sequences – 7:50 – Color – Silent – BLUEGILL and STARFISH were high-altitude nuclear tests, part of Operation Fishbowl, conducted in the Johnston Island area of the Pacific Proving Ground in 1962. These tests produced auroral effects, a special feature of explosions where the extreme brightness of the fireball is visible at great distances. Within a second or two after the burst, a brilliant aurora appears from the bottom of the fireball. The formation of the aurora is attributed to the motion, along the lines of the earths magnetic field, of beta particles emitted by the radioactive fission fragments. About a minute after the detonation, the aurora could be observed in the Samoan Islands, 2000 miles from the detonation. These auroras could be seen for approximately 20 minutes. The video shows footage of the auroras from Somoa, Mauna Loa (Hawaiian Islands) and Tongtapu (Tonga Islands) at various film speeds. Dominic on Fishbowl Phenomenon – 1:12 – Color – Silent – Operation Fishbowl was the high-altitude testing portion of a larger Operation Dominic I. This video is a compilation of footage of the five nuclear tests comprising Operation Fishbowl conducted in the Johnston Island area of the Pacific Proving Ground in 1962. A high-altitude burst is one occurring above 100,000 feet. The video does not identify the date, time or name of the tests. When a nuclear weapon detonates at a high altitude, many of the effects are attenuated. Most of the x-ray energy is absorbed in the air, which decreases the fireball temperature. Absorption of thermal x-ray energy also decreases the energy available for a shock wave. This all results in the development of a toroidal or donut-shaped cloud instead of the usual mushroom shape of ground or near ground explosions. This also shows the auroral effect of high-altitude explosions where the extreme brightness of the fireball is visible at great distances. Within a second or two after the burst, a brilliant aurora appears from the bottom of the fireball. The formation of the aurora is attributed to the motion, along the lines of the earths magnetic field, of beta particles emitted by the radioactive fission fragments. About a minute after the detonation, the aurora can be observed from as far away as 2000 miles. These auroras can be seen for approximately 20 minutes. Fishbowl XR Summary – 34:38 – Black&White – Silent – The video shows the five, rocket-launched, Operation Fishbowl tests at various camera speeds and from different camera locations. Operation Fishbowl was the Department of Defenses high-altitude testing portion of Operation Dominic I, conducted in the Johnston Island area of the Pacific Proving Ground in 1962. In a high-altitude blast, many of the effects are attenuated, resulting in a toroidal or donut-shaped cloud instead of the mushroom cloud from a surface burst. These weapons-effects tests, launched by Strypi, Thor, and Nike Hercules rockets, were as follows: STARFISH PRIME, July 9, 400-kilometer altitude, 1.4 megaton CHECKMATE, October 20, tens of kilometers altitude, low (less than 20 kt) BLUEGILL 3 PRIME, October 26, tens of kilometers altitude, submegaton (less than 1 Mt, but more than 200 kt) KINGFISH, November 1, tens of kilometers altitude; submegaton (less than 1 Mt, but more than 200 kt) TIGHTROPE, November 4, tens of kilometers altitude, low (less than 20 kt) Two goals of these tests were to determine if radiation and blast and heat effects of high- altitude detonations were capable of neutralizing an enemy reentry vehicle and capable of determining the blackout effects on radar and communications of various yields and altitudes of bursts.

https://www.osti.gov/opennet/reports/plowshar.pdf

On July 9, 1962, at 09:00:09 Coordinated Universal Time (11:00:09 p.m. on July 8, Honolulu time), the Starfish Prime test was detonated at an altitude of 250 miles (400 km). The coordinates of the detonation were 16°28′N 169°38′WCoordinates:  16°28′N 169°38′W.[1] The actual weapon yield came very close to the design yield, which various sources have set at different values in the range of 1.4 to 1.45 megatons (6.0 PJ). The nuclear warhead detonated 13 minutes 41 seconds after liftoff of the Thor missile from Johnston Atoll.[5] Starfish Prime caused an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that was far larger than expected, so much larger that it drove much of the instrumentation off scale, causing great difficulty in getting accurate measurements. The Starfish Prime electromagnetic pulse also made those effects known to the public by causing electrical damage in Hawaii, about 898 miles (1,445 km) away from the detonation point, knocking out about 300 streetlights,[6] setting off numerous burglar alarms, and damaging a telephone company microwave link.[7] The EMP damage to the microwave link shut down telephone calls from Kauai to the other Hawaiian islands.[8] A total of 27 small rockets were launched from Johnston Atoll to obtain experimental data from the Starfish Prime detonation. In addition, a large number of rocket-borne instruments were launched from Barking Sands, Kauai, in the Hawaiian Islands.[9] A large number of United States military ships and aircraft were operating in support of Starfish Prime in the Johnston Atoll area and across the nearby North Pacific region. A few military ships and aircraft were also positioned in the region of the South Pacific Ocean near the Samoan Islands. This location was at the southern end of the magnetic field line of the Earth’s magnetic field from the position of the nuclear detonation, an area known as the “southern conjugate region” for the test. An uninvited scientific expeditionary ship from the Soviet Union was stationed near Johnston Atoll for the test, and another Soviet scientific expeditionary ship was in the southern conjugate region near the Samoan Islands.[10] After the Starfish Prime detonation, bright auroras were observed in the detonation area, as well as in the southern conjugate region on the other side of the equator from the detonation. According to one of the first technical reports:[9] The visible phenomena due to the burst were widespread and quite intense; a very large area of the Pacific was illuminated by the auroral phenomena, from far south of the south magnetic conjugate area (Tongatapu) through the burst area to far north of the north conjugate area (French Frigate Shoals)… At twilight after the burst, resonant scattering of light from lithium and other debris was observed at Johnston and French Frigate Shoals for many days confirming the long time presence of debris in the atmosphere. An interesting side effect was that the Royal New Zealand Air Forcewas aided in anti-submarine maneuvers by the light from the bomb. These auroral effects were partially anticipated by Nicholas Christofilos, a scientist who had earlier worked on the Operation Argus high-altitude nuclear shots.

16°28′N 169°38′W.[1] The actual weapon yield came very close to the design yield, which various sources have set at different values in the range of 1.4 to 1.45 megatons (6.0 PJ). The nuclear warhead detonated 13 minutes 41 seconds after liftoff of the Thor missile from Johnston Atoll.[5] Starfish Prime caused an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that was far larger than expected, so much larger that it drove much of the instrumentation off scale, causing great difficulty in getting accurate measurements. The Starfish Prime electromagnetic pulse also made those effects known to the public by causing electrical damage in Hawaii, about 898 miles (1,445 km) away from the detonation point, knocking out about 300 streetlights,[6] setting off numerous burglar alarms, and damaging a telephone company microwave link.[7] The EMP damage to the microwave link shut down telephone calls from Kauai to the other Hawaiian islands.[8] A total of 27 small rockets were launched from Johnston Atoll to obtain experimental data from the Starfish Prime detonation. In addition, a large number of rocket-borne instruments were launched from Barking Sands, Kauai, in the Hawaiian Islands.[9] A large number of United States military ships and aircraft were operating in support of Starfish Prime in the Johnston Atoll area and across the nearby North Pacific region. A few military ships and aircraft were also positioned in the region of the South Pacific Ocean near the Samoan Islands. This location was at the southern end of the magnetic field line of the Earth’s magnetic field from the position of the nuclear detonation, an area known as the “southern conjugate region” for the test. An uninvited scientific expeditionary ship from the Soviet Union was stationed near Johnston Atoll for the test, and another Soviet scientific expeditionary ship was in the southern conjugate region near the Samoan Islands.[10] After the Starfish Prime detonation, bright auroras were observed in the detonation area, as well as in the southern conjugate region on the other side of the equator from the detonation. According to one of the first technical reports:[9] The visible phenomena due to the burst were widespread and quite intense; a very large area of the Pacific was illuminated by the auroral phenomena, from far south of the south magnetic conjugate area (Tongatapu) through the burst area to far north of the north conjugate area (French Frigate Shoals)… At twilight after the burst, resonant scattering of light from lithium and other debris was observed at Johnston and French Frigate Shoals for many days confirming the long time presence of debris in the atmosphere. An interesting side effect was that the Royal New Zealand Air Forcewas aided in anti-submarine maneuvers by the light from the bomb. These auroral effects were partially anticipated by Nicholas Christofilos, a scientist who had earlier worked on the Operation Argus high-altitude nuclear shots.

According to U.S. atomic veteran Cecil R. Coale,[11] some hotels in Hawaii offered “rainbow bomb” parties on their roofs for Starfish Prime, contradicting some reports that the artificial aurora was unexpected. “A ‘Quick Look’ at the Technical Results of Starfish Prime” (August 1962) states:[9] At Kwajalein, 1,400 [nautical] miles [2,600 km; 1,600 mi] to the west, a dense overcast extended the length of the eastern horizon to a height of 5 or 8 degrees. At 0900 GMT a brilliant white flash burned through the clouds rapidly changing to an expanding green ball of irradiance extending into the clear sky above the overcast. From its surface extruded great white fingers, resembling cirro-stratus clouds, which rose to 40 degrees above the horizon in sweeping arcs turning downward toward the poles and disappearing in seconds to be replaced by spectacular concentric cirrus like rings moving out from the blast at tremendous initial velocity, finally stopping when the outermost ring was 50 degrees overhead. They did not disappear but persisted in a state of frozen stillness. All this occurred, I would judge, within 45 seconds. As the purplish light turned to magenta and began to fade at the point of burst, a bright red glow began to develop on the horizon at a direction 50 degrees north of east and simultaneously 50 degrees south of east expanding inward and upward until the whole eastern sky was a dull burning red semicircle 100 degrees north to south and halfway to the zenith obliterating some of the lesser stars. This condition, interspersed with tremendous white rainbows, persisted no less than ninety minutes. At zero time at Johnston, a white flash occurred, but as soon as one could remove his goggles, no intense light was present. A second after shot time a mottled red disc was observed directly overhead and covered the sky down to about 45 degrees from the zenith. Generally, the red mottled region was more intense on the eastern portions. Along the magnetic north-south line through the burst, a white-yellow streak extended and grew to the north from near zenith. The width of the white streaked region grew from a few degrees at a few seconds to about 5–10 degrees in 30 seconds. Growth of the auroral region to the north was by addition of new lines developing from west to east. The white-yellow auroral streamers receded upward from the horizon to the north and grew to the south and at about 2 minutes the white-yellow bands were still about 10 degrees wide and extended mainly from near zenith to the south. By about two minutes, the red disc region had completed disappearance in the west and was rapidly fading on the eastern portion of the overhead disc. At 400 seconds essentially all major visible phenomena had disappeared except for possibly some faint red glow along the north-south line and on the horizon to the north. No sounds were heard at Johnston Atoll that could be definitely attributed to the detonation. Strong electromagnetic signals were observed from the burst, as were significant magnetic field disturbances and earth currents. While some of the energetic beta particles followed the Earth’s magnetic field and illuminated the sky, other high-energy electrons became trapped and formed radiation belts around the Earth. There was uncertainty about the composition, magnitude and potential adverse effects from this trapped radiation after the detonation. The weaponeers became quite worried when three satellites in low Earth orbit were disabled. These included TRAAC and Transit 4B.[13] The half-life of the energetic electrons was only a few days. At the time it was not known that solar and cosmic particle fluxes varied by a factor of 10, and energies could exceed 1 MeV. In the months that followed these man-made radiation belts eventually caused six or more satellites to fail,[14] as radiation damaged their solar arrays or electronics, including the first commercial relay communication satellite, Telstar, as well as the United Kingdom’s first satellite, Ariel 1.[15] Detectors on Telstar, TRAAC, Injun, and Ariel 1 were used to measure distribution of the radiation produced by the tests.[16] In 1963, it was reported that Starfish Prime had created a belt of MeV electrons.[17] In 1968, it was reported that some Starfish electrons had remained for 5 years.[18]

Herman Hoerlin, soul dyadic letters to Kate

The Kate and Herman Hoerlin Collection documents the lives of this couple. The core of the collection consists of a copious amount of their letters to each other during their courtship, coinciding with the rise of Nazism; other documentation includes research correspondence and copies of official documents relating to their story as well as correspondence and other papers from their lives in the United States. The collection follows the original order established by Bettina Hoerlin; her detailed inventory is present in Series IV as is a seven-page description of the collection (“The Tietz/ Schmid/ Hoerlin Story”) interspersed with biographical details that give an overview of the couple’s lives. The collection culminated in the creation of Bettina Hoerlin’s book, Steps of Courage: My Parents’ Journey from Germany to America. The first series of the collection contains the correspondence of Kate Schmid and Herman Hoerlin with each other. It includes about five hundred love letters between Kate Schmid and Herman Hoerlin (always referred to as Hoerlin) during their four year courtship, focusing on their relationship but also including details of their work and their efforts to receive permission to marry. Among many other topics mentioned in the letters are the growth of National Socialism in German society and its effects upon their lives, including Kate Schmid’s classification as a Mischling and her many trips to Berlin to meet with government and Nazi Party officials regarding her status, permission to marry, and reparations for the death of her first husband Willi Schmid. Kate Schmid’s friendships with other leading figures in cultural, intellectual and industrial circles of the time are referenced in the letters, among them Oswald Spengler, Karl Vossler, Peter Doerffler, Oswald Bumke, August Bostroem, Paul Reusch, Curt and Karl Haniel, Felix Hausdorff, William Furtwaengler and Pablo Casals. A smaller number of Hermann Hoerlin’s letters to Kate Schmid are also present; they mention other well-known German mountain climbers and Nazi attempts to take over the 240,000 member German Austrian Alpine Club. Included in this series is a bound booklet with preliminary translations of the letters, a brief preface, accompanying notes, and a list of significant individuals. A few letters in this series are from others to Kate or Herman. Series II: Research Initiatives contains Bettina Hoerlin’s accumulated archival research. Included is her own research correspondence with organizations and other researchers as well as copies of official correspondence from German government officials relating to the marriage of Kate Schmid and Herman Hoerlin, the death of Willi Schmid and reparations for his murder. The third series holds documentation of Kate and Herman Hoerlin’s lives in the United States. Much of this material relates to Herman Hoerlin’s professional career, such as his time at Agfa Ansco in Binghamton, his search for other employment and his years at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Documentation of his wartime life includes objections about Nazi sympathizers employed at Agfa Ansco and resistance to working with these individuals, his aid to the U.S. Army by providing mountaineering maps of the Alps, and restrictions placed upon the family as “enemy aliens.” https://archives.cjh.org//repositories/5/resources/7290

PIMCO (Pacific Investment Management Company) - should become IPIMCO? Indo-Pacific

Gross was born in Middletown, Ohio, the son of Shirley (née Tait), a homemaker, and Sewell Mark Gross, a sales executive for AK Steel Holding.[3][4] Part of his family is originally from Winnipeg, Canada.[5] He was raised a Presbyterian.[6] He moved with his parents to San Francisco in 1954.[4] Gross graduated from Duke University in 1966 as an Angier B. Duke Scholar, and with a degree in psychology.[7] At Duke, he joined Phi Kappa Psi.[8] He then served in the Navy from 1966 to 1969 as an assistant chief engineer aboard the USS Diachenko, leading several sorties of SEALS to landing sites along the coast of Vietnam.[9] He retired from the Navy in 1970 with the Tet combat and Vietnam active service ribbons. Gross earned an MBA from the UCLA Anderson School of Management in 1971. Gross briefly played blackjack professionally in Las Vegas, Nevada, and has said that he applies many of his gambling methods for spreading risk and calculating odds to his investment decisions. In 2014 Gross was reported as one of a number of “prominent investors [who] have taken to Transcendental Meditation” Some of those who control investment management’s huge accumulations of capital now earn as much as those at the pinnacle of global banking. In 2014, with the aid of insiders, the Bloomberg journalist Barry Ritholtz esti- mated the remuneration of the two highest-paid staff of PIMCO, the Pacific Investment Management Company. Bill Gross, PIMCO’s co-founder and manager of its Total Return Fund, earned a bonus in 2013 of $290 million. PIMCO’s then chief executive, Mohamed El-Erian, took home $230 million. Admittedly, a quirk of PIMCO’s history—a profit-sharing arrangement with Allianz, the German insurance company that bought a majority stake in PIMCO in 2000—made those figures atypically large: for instance, Black- Rock’s chief executive and co-founder, Larry Fink, earned a mere $22.9 million in 2013 (Ritholtz 2014). Nevertheless, average pay at investment management firms is high. Research by the think tank New Financial (Wright 2015) esti- mates the average for 2014 as $263,000, which was within touching distance of the $288,000 average for global investment banking. The Financial Stability Board, based in Basel, guides the global regulation of financial markets. It has considered adding the world’s biggest investment managers, such as BlackRock and PIMCO, to the list of the thirty banks and nine insurance companies that it considers ‘Sifis’ (systemically important financial institutions) and subjects to enhanced scrutiny and an additional layer of capital requirements. Eventually, though, the Board decided not to, but—reportedly—not for an entirely reassuring reason. There are established ways of regulating banks and insurance companies, but the Board ‘did not know how it would regulate’ investment management firms, beyond some simple measures to reduce the risk of fire sales (Jopson et al. 2015). The Financial Stability Board is not alone in its puzzlement when confront- ing investment management. As Haldane put it, ‘[a]nalysing and managing the behaviour of asset managers is . . . a greenfield site’ (2014: 14). While that is an exaggeration (we outline the findings of the existing research on invest- ment management later in this chapter), research is much sparser than might be expected given the size and importance of the investment management sector.

TPP, Gravity Loss

Trump: I like bilateral, because if you have a problem, you terminate. When you’re in with many countries — like with TPP, so you have 12 if we were in — you don’t have that same, you know you don’t have that same option. But somebody asked me the other day, ‘Would I do TPP?’ Here’s my answer — I will give you a big story. I would do TPP if we made a much better deal than we had. We had a horrible deal. The deal was a horrible deal. NAFTA’s a horrible deal, we’re renegotiating it. I may terminate NAFTA, I may not — we’ll see what happens. But NAFTA was a — and I went around and I tell stadiums full of people, I’ll terminate or renegotiate. Kernen: So you might re-enter, or? Are you opening up the door to re-opening TPP, or? Trump: I’m only saying this. I would do TPP if we were able to make a substantially better deal. The deal was terrible, the way it was structured was terrible. If we did a substantially better deal, I would be open to TPP. Kernen: That’s interesting. Would you handicap … ? Trump: Are you surprised to hear me say that? Kernen: I am a little bit, yeah, I’m a little taken aback. Trump: Don’t be surprised, no, but we have to make a better deal. The deal was a bad deal, like the Iran deal is a bad deal, these are bad deals. Kernen: Maybe NAFTA, maybe not NAFTA, can you give me any indication of which way you’re leaning because there’s a lot of people, a lot of the CEOs that have been on here, they all seem to acknowledge that it’s 30 years later and there’s a lot of changes that make a lot of sense, but to not abandon the deal. Will you — Trump: Hey Joe, we have a trade deficit with Mexico. Mexico, $71 billion a year, right? We have a trade deficit with Canada of a substantial amount of money. I have a number, but they keep arguing it, they keep saying, so I won’t say it, I won’t tell you it’s $17 million, OK? We have a trade deficit with Canada. We have a massive trade deficit with Mexico. We’ve got to do something. We can’t continue to do this. Kernen: Are you leaning towards staying in or would you really go out completely? Trump: I’ve always said … during campaign and as you have noticed, and as you have actually said a couple of times which I have always appreciated, I have fulfilled a lot of what I’ve said and I’m only here a year, you know I think I have four years, and maybe another four years, OK? … Joe, we have a $71 billion a year deficit with Mexico. We’ve got to do something, we can’t have that. So, will it be renegotiated? We’re trying right now with [U.S. Trade Representative] Bob Lighthizer and the whole group. I think we have a good chance but we’ll see what happens. Trump: But ultimately the dollar, because our country is going to get so much stronger economically, if you look at what’s happened to our country over the — look, I’ve been talking about this with you for 25 years. Trade. It started with Japan, morphed into China, now it’s China, Japan, it’s everybody. And everybody has taken advantage of our country. They have ripped our country off. You look at what they do. I saw something on motorcycles today with a certain country. Why should I say? But they sell motorcycles into our country, no tax. We sell motorcycles into their country — Harley-Davidsons, the greatest, right? We sell them into their country, 100 percent tax. Not going to happen. The word “reciprocal” is the most important word with Donald Trump when it comes to what the subject that we talk about and the subject that CNBC covers so well — especially you, by the way, because I don’t agree with all of you people, but that’s OK. But reciprocal. I want reciprocal. If they’re going to charge us 100 percent for a motorcycle, it should be 100 percent the other way, too. And you know, when you mention a tax at the border, a 10 percent tax on the border for everything coming in, I’m a free trader. Totally. I’m a fair trader. I’m all kinds of trader, but I want reciprocal. Because when China’s charging us a fortune to send products in and making it impossible for the product to get there — and many other countries, by the way, not just China. China’s the biggest. And then we charge them nothing to sell their stuff here. It’s not fair. When you use the word “reciprocal” everybody understands that. If they do it to you, you do it to them and everybody understands it, Joe. And you’re going to see a lot of that in my administration. And you’re already seeing it. (https://www.cnbc.com/2018/01/26/president-trumps-full-remarks-on-nafta-tpp-in-cnbc-interview.html)

Notes

https://www.thespacereview.com/article/3811/1 – Modern Monetary Theory and Lunar Development (Vidvuds Beldavs, 2019)

https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB479/docs/EBB-Moon02.pdf – A Study of Lunar Research Flights, Vol 1 by I. Reiffel, Armour Research Foundation of Illinois Institute of Technology, 19 June 1959, Project A119

https://www.nature.com/articles/35011148.pdf?origin=ppub – Sagan breached security by revealing US work on lunar bomb project

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space-based_solar_power – Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP)

http://addsdonna.com/old-website/ADDS_DONNA/Science_Fiction_files/2_Asimov_Reason.pdf – Reason by Isaac Asimov

Is is always solar noon in space and full sun

Tianxia and the lunar / solar dyad in Chinese thought

One reason that China’s modernizers rejected the lunar calendar was that it slowly goes off course. Twelve lunar cycles is just 354 days. That’s about ten days short each year. The calendar is corrected every three years by adding a leap month, but this still means that events on the lunar calendar shift relative to the solar calendar from year to year. Sometimes Chinese New Year is in January, sometimes in February.

This might seem insignificant; after all, other religious calendars have shifting dates for their holidays, too. But China’s calendar did more than track religion; it set the pattern for work as well. In agricultural societies like traditional China, farmers needed reliable guideposts to the seasons: when the earth would warm, the rains fall, or the frosts arrive. To figure this out, people had to gauge where the earth was relative to the sun, not the moon.

They did that by tracking the way the sun appears to move through the stars. From the earth’s position as we revolve around the sun, the stars behind the sun appear to be moving. This idea is familiar to Westerners through the signs of the zodiac, which tell which constellation is passing behind the sun. Of course, it is we who are moving around the sun—not the sun through the stars—but the basic idea is right: it tells the earth’s location on its annual 360-degree circuit around the sun. The movement is exact and predictable: about 1 degree around the sun each day of the year.

Ancient Chinese used this principle to group days into fifteen- to sixteen-day mini-seasons called jieqi, or solar terms. Each year has twenty-four—six for each season—and each of the twenty-four has its own special weather patterns, poems, aphorisms, and even rules about which foods to eat—which ones, for example, would cool the body in the summer, warm it in the winter, or replenish fluids in dry months. Their names evoke another, rural era: Grain Rain, Summer Harvest, Frost Descends, Lesser Snows, Greater Cold. In recent years, these solar terms have made a comeback as cultural symbols. In the 1990s, artists began to use them allegorically for political and cultural events. Around 2010, consumer culture discovered them. Magazines devoted special issues to the solar terms, reintroducing readers to the traditional calendar and suggesting the appropriate food, tea, and clothing. In Beijing, a grocery store chain hired folk culture experts to devise a line of special foods for each of the twenty-four solar terms: minced-garlic pies to fight off the increased bacteria in the warming air of the Vernal Equinox; cooling green-bean cakes for Lesser Heat; and a hearty pig’s elbow to build up one’s constitution for the cold days of Autumn Commences. Books and apps explained the poems, myths, and fables associated with them. Elementary schools invited guest lecturers to explain the concept. Friends started signing e-mails with a greeting for key solar terms: A Peaceful Winter Solstice to You! One of the most evocative solar terms is jingzhe, or the Awakening of the Insects. It occurs in early March when spring thundershowers were believed to waken dormant insects. The last of the six winter solar terms, it falls when the earth is 345 degrees around its orbit and planting is just around the corner. After the excitement of the New Year celebrations has faded, the world rouses itself. Tao Yuanming, a reclusive Daoist poet of the fourth century, put it like this: Spring approaches, bringing timely rains / Early thunder, erupting from the east / Hibernating animals, hidden but shocked awake. / Plants and trees, across the land, slowly open up.”

Dongzhi, or the Winter Solstice, is the year’s darkest hour. It is the shortest day of the year, a time dominated by yin, whose main property is darkness. But Chinese prefer to look ahead. Instead of darkness, they see it as the beginning of the ascent of yang, or light—the ultimate expression of the Chinese saying wu ji bi fan: “When things reach their extreme, they must move in the opposite direction.” In politics, this means that extreme openness will move toward contraction, but also the opposite—a reason for optimism during a time of oppression. We often see China in clichés—booms and busts, contractions and crackdowns—and are constantly trying to define it by today’s headlines. This extreme day reminds us to take the long view. Now, as we are 270 degrees through our journey to spring, the chilliest solar terms await: Lesser Cold and Greater Cold, which fall in January. Chinese count off these icy days with a numbers game. The final eighty-one days to spring are divided into nine periods of nine days each—the nine nines. The days start cold, then begin to warm until finally the fields can be plowed, as “as in this popular rhyme: One, two, hands freeze outside / Three, four, ice supports your weight / Five, six, willows start to green / Seven, rivers open / Eight, geese return / Nine, add another nine, and / Oxen fill the fields.

The six mini-seasons that make up China’s summer are about heat and passion, growth and harvest. This duality is symbolized by one of the most important of the summer solar terms, mangzhong, a compound word meaning harvest and planting. Mang means the ear, or grain-bearing tip of a plant—the period when grains like wheat, barley, and peas already have grain in the ear and must be harvested. Zhong means planting, because this is also when autumn crops like maize, sorghum, millet, and soybeans must be put in the ground; any later, and they won’t be ripe before the autumn frosts. This time in early June is so important that until recently even city people could ask for time off work to go back to their homes in the countryside to help out. Now the earth is seventy-five degrees on the plane around the sun, and the next solar terms mark the height of summer: xiazhi, or Summer Solstice in late June, when the days are the longest, and then Little Heat and Big Heat in July. By then the hottest days are already past, and even if it does seem early, the next solar term is Autumn Commences in early August. The summer is home to two of the year’s most colorful festivals. One is the lunar calendar’s second festival of the dead, the Hungry Ghosts Festival, which falls on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, usually in August, when people who died unhappily have to be placated so they do not wander the world and bother the living. The other big festival is Duanwu, or the Dragon Boat Festival, the second festival of the living—the others are the Lunar New Year and the Mid-autumn Festival.

Excerpts From: Ian Johnson. The Souls of China

one of the earliest images you took you called moonlines,

and now you've come back (06 May 2020) full orbit

to the idea of the solar / lunar heartland

Think of two parallel lines, he said. One is the life of Lee H. Oswald. One is conspiracy to kill the president. What bridges the space between them? What makes a connection inevitable? There is a third line. It comes out of dreams, visions, inhibitions, prayers, out of the deepest levels of the self. It’s not generated by cause and effect like the other two lines. It’s a line that cuts across causality, cuts across time. It has no history that we can recognise or understand. But it forces a connection. It puts a man on the path of his destiny.

Like his surrogate, Nicholas Branch, Delillo takes as his subject not politics or violent crime but men in small rooms. Branch sees that after Oswald, men in America are no longer required to lead lives of quiet desperation. You apply for a credit card, buy a handgun, travel through cities, suburbs and shopping malls, anynoymous, anonymous, looking for a chance to take a shot at the first puffy empty famous face. Such men have come out of nowhere to shape both history and consciousness, especially as it informs a widespread contemporary paranoia, and Delillo seeks, without denying the paranoia, to offer what he characterises as fictive consolation, a story that rescues history from its confusions.” That is, he devises but does not privilege a conspiracy narrative that artfully blends and to come degree reconciles seemingly contradictory facts. As he explains in interviews, he bases his plot on certain plausible elements in the historical record: the dangerously concurrent anger of disgruntled CIA operatives, Bay of Pigs survivors, and mobsters yearning for a return to the Havana paradise from which Fidel had expelled them. Readers, then, are ultimately to understand the book not in terms of this or that theory affirmed, nor as an argument for or against the lone-gunman hypothesis, but rather as a sense-making of history centred on the role of the irrational and its instrument, the man who, as Delillo told Ann Arensberg, ‘stepped outside history and let the forces of destiny move him where they would – non-historical forces like dreams, coincidences, intuitions, the alignment of the heavenly bodies, all these things.

Delillo’s research and his cunning embrace of the Oswald persona that lead him to the recognition that the most significant element in the bottomless mystery of Kennedy’s muder was the emergence on the historical stage, from which they had been excluded, of hitherto faceless men who had spent their lives dreaming of their affinities with principled, notorious, or merely intellectual or scholarly dwellers in small rooms: revolutionaries such as Trotsky and Castro, spies such as Francis Gary Powers (Oswald looks in on him in a Kremlin cell), historians history and dreams, what a sense of destiny he had, locked in the miniature room, creating a design, a network of connections. It was a second existence, the private world floating out to three dimensions.

At times, Delillo observes in the Rolling Stone article, Oswald’s career has the familiar feel of those lives of dedicated and obsessed men who undergo long periods of isolation, either enforced or voluntary, who live close to death for the sake of some powerful ideal or evil, and who eventually emerge as great leaders or influential thinkers, outsized figures in the history of revolution and war. One thinks of Yeats’s image, in Easter 1916 for the ideologue: an unyielding stone in the midst of life’s stream. But this is a modernist archetype, and Delillo knows that Kennedy’s assassin represents another, postmodern model of the person in the small room. Neither Hitler nor Mandela, Oswald is merely a nonentity whose violent resentments, coalescing around mail-order weapon and fantasies of pseudonymous intrigue set the pattern for Sirhan Sirhan, James Earl Ray, Arthur Bremer, John Hinckley et. al.

What really figures here is neither political conspiracy nor coherent individual purposes (however murderous the intent). Rather, it is the workings of dreams, coincidence, astrology – all that lies outside systems of historical logic. Only the ‘language of the night sky’ can express the truth behind Oswald’s act, but it is an astrological ‘truth at the edge of human affairs’.

How has the North-South inversion affected this phenomenon of reciprocal simulation?

All geostrategic organization was founded on an East-West orientation. The great traditional Indo-European emigration flows went in this direction. All the obligatory places of passage were hotbeds of subversion in the political sense, and ofdomination in the military sense. It was just as much the Balkans, the Dardanelles, the Bosporus, as the Mediterranean, Egypt, the Suez Canal, and Gibraltar with what’s happening around it. You had an entire East-West confrontation. Now, there is an absolute North-South inversion. By North-South, I don’t mean following a developed country/ underdeveloped country axis, but strictly in geographic terms. The Falklands war showed it. It’s the end of narrow passes, of the importance of passages, straits, isthmuses. It began with the Suez campaign, which was still an East-West war. The Suez War brought about an extraordinary transformation in containers and ships that passed by Cape Horn. There was an inversion: flows no longer passed through the little canals-Suez, Panama, Gibraltar, or the Bosporus-but into the open sea: Cape Horn, Cape of Good Hope, the Indian Ocean, and ofcourse South Africa and Antarc tica. This inversion is related to the arteries of the Persian Gulf and the passage of the great oil channels. But it’s more than that: It’s the entire East-West conflict tipping toward the North-South axis. Power becomes a function of deterrence. It’s no longer simply a matter of quantitative might-the number of warships afloat, the Home Fleet-it’s also the nuclear submarines on which deterrence rests. We saw it with the START agreements. The Americans pro posed reducing ground forces by half, since the Russians get their power from ground forces and the Americans from nuclear sub marines. The Americans played the card of naval power-still qualitative-the submarine being their trump card. A nuclear sub marine passing Suez or Panama, however, is no longer really deterrent. It’s not really deterrent except when on the open sea. So this disqualification affects all arms systems, all power relations. They realize that they can only play on the Southern passageways. From this point on, the Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean passage leads up toward the Atlantic, the North Atlantic/South Atlantic, and Pacific passageway. And here the Antarctic becomes a crucial geo strategic pole. It’s not by chance that everyone got so involved in the Falklands war. Some say the conflict was over oil-that wasn’t the question. The question was that there was a new geostrategic situation and that the Antarctic would be its center, its axis. Once the North-South axis takes prevalence on the geostrategic level, we notice that the struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States is no longer the same. The fate of America, Latin America, and Europe is no longer the same. No wonder America isn’t being generous with Europe at the moment. There is an inversion, a tipping which is worth analyzing, which is linked to both the submarines’ freedom ofmovement and the great oil flows which no longer pass by straits and canals. The two empires are risking internal disintegration, but eternally there seems to be a process ofmutualjustification, a reciprocal geostrategic reinforcement which bodes illfor thefuture. The Russian-American coupling began as opposition, and it’s slowly becoming, with technical progress and the reduction of the world to nothing, a conspiracy. I once joked that we would perhaps see a take-over by the Soviet and American military class, and that at bottom they could very well grab power together. A take-over on the scale of the Pure State. I even worked out a whole situation, saying their capital would probably be in Switzerland. . . . At the same time, it would mean negating the motivation for war. That’s allpoliticalfiction; but what we have in reality is a struggle which is all the more irrepressible in that the conflict runs in idle. A struggle means to organize, master, produce a space-time. Ifthere are geostrategic inversions, it’s because there are still ancient situa tions, because we still haven’t reached chrono-political nirvana, because there’s still space somewhere, and this space still imposes a few constraints (but fewer and fewer)-since passage by Cape Horn and Latin America is still a deterritorialization. The fact that naval power and orbital weapons are absolute power shows quite well that physical space is dematerializing and losing more and more of its importance.

BOMBING AND THE SYMPTOM TRAUMATIC EARLINESS AND THE NUCLEAR UNCANNY

Many used the Japanese word bukimi, meaning weird, ghastly, or unearthly, to describe Hiroshima’s uneasy combination of continued good fortune and expectation of catastrophe. People remembered saying to one another, “Will it be tomorrow or the day after tomorrow?” One man described how, each night he was on air-raid watch, “I trembled with fear. . . . I would think, “Tonight it will be Hiroshima.” These “premonitions” were partly attempts at psychic preparation, partly a form of “imagining the worst” as a magical way of warding off disaster.

—Robert J. Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (1967)

Robert J. Lifton’s pathbreaking work on the survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima focuses on the psychological aftermath of the bomb, but opens with a brief and surpris- ing section called “Anticipation.” Given the instantaneous and unprecedented devasta- tion caused by the first atomic bomb, the anticipation of so singular an experience is just as difficult to imagine as its subsequent assimilation. In fact, the unassimilable nature of traumatic violence would seem to depend in some way upon the impossibility of its anticipation, as Lifton implies: “Neither past experience nor immediate perceptions—the two sources of prior imagination—could encompass what was about to occur.” Yet Lifton also records an expectant, premonitory atmosphere in Hiroshima during the weeks be- fore the bombing, a compound of past experience and immediate perceptions that, while inadequate to “encompass” the eventual experience of the bomb, cannot simply be dis- missed as speculation that found an accidental correlate in the nuclear event. While no one in Hiroshima knew ahead of time what would occur on August 6, 1945, many had noted the city’s eerie exemption from conventional bombardment and speculated as to the reasons for it. During the summer of 1945, a series of rumors circulated in Hiroshima, rumors attributing the sparing of the city, variously, to its modest military and industrial significance; to the presence of prominent foreigners there, possibly including Presi- dent Truman’s mother; to important American prisoners-of-war supposedly held in the city; to the number of its citizens who had emigrated to the US; to the presence of large numbers of American spies living among its citizens; to its physical appeal in the eyes of Americans who had saved the city as a site for their postwar occupation villas; and, most wishfully, to the wartime grace of a cartographic error: “We thought that perhaps the city of Hiroshima was not on the American maps” [Lifton 15–17]. Other inhabitants of the city feared that Hiroshima appeared all too prominently on US maps, but had been set aside for “something unusually big”—perhaps the inundation of the city by floodwaters that could be released by the bombing of a massive upstream dam. Still others spoke of a “special bomb” [PWRS 220–22; Lifton 17]. All these rumors re- sponded to citizens’ impression that their city had been in some way singled out, and the term bukimi—also meaning “ominous” or “uncanny”—spoke to the suspended ques- tion of whether Hiroshima and its inhabitants had been singled out for preservation or for annihilation. The survivors who recollected their anticipatory bukimi years after the bombing may have retrospectively amplified their memories of weird expectation, perhaps as a way of attempting to master an incommensurable and singular event by installing it within a narrative of causality, continuity, even prophecy. Nonetheless, the bukimi ex- perienced by inhabitants of Hiroshima should not be understood as pure retrospection, nor as groundless hunch, since it arose from a series of empirical observations later revealed to have a single and coherent origin in US military strategy.

Break out of the penumbral straitjacket, where mental content is only a couple of metres in each direction, our minds are more expansive than this, remember Massumi on Clausewitz, fog of war the structurally divided, bihemispheric brain, is not a new invention: bihemispheric structure must have offered possibilities that were adaptive. On the one hand, there is the context, the world, of ‘me’ – just me and my needs, as an individual competing with other individuals, my ability to peck that seed, pursue that rabbit, or grab that fruit. I need to use, or to manipulate, the world for my ends, and for that I need narrow-focus attention. On the other hand, I need to see myself in the broader context of the world at large, and in relation to others, whether they be friend or foe: I have a need to take account of myself as a member of my social group, to see potential allies, and beyond that to see potential mates and potential enemies. […] Why are the hemispheres separate? The separation of the hemispheres seems not accidental, but positively conserved, and the degree of separation carefully controlled by the band of tissue that connects them. This suggests that the mind, and the world of experience that it creates, may have a similar need to keep things apart.

The ratio of grey to white matter also differs. The finding that there is more white matter in the right hemisphere, facilitating transfer across regions, also reflects its attention to the global picture, where the left hemisphere prioritises local communication, transfer of information within regions […] When dealing with complex cognitive and emotional events, all references to localisation, especially within a hemisphere, but ultimately even across hemispheres, need to be understood in that context. Having said that, how can one make a start? One method is to study subjects with brain lesions. This has certain advantages. When a bit of the brain is wiped out by a stroke, tumour or other injury, we can see what goes missing, although interpretation of the results is not always as straightforward as it might seem.18 Another is to use temporary experimental hemisphere inactivations. One way in which this is achieved is by the Wada procedure, most commonly carried out prior to neurosurgery in order to discriminate which hemisphere is primarily responsible for speech. This involves injecting sodium amytal or a similar anaesthetic drug into the blood supply of one carotid artery at a time, thus anaesthetising one half of the brain at a time, while the other remains active. Another way is through transcranial magnetic stimulation techniques, which uses an electromagnet to depress (or, depending on the frequency, enhance) activity temporarily in one hemisphere, or at a specific location within the hemisphere. In the past a similar opportunity came from unilateral administration of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

A binary system is a system of two astronomical bodies which are close enough that their gravitational attraction causes them to orbit each other around a barycenter. In astronomy, a double planet (also binary planet) is a binary system where both objects are of planetary mass. Currently, the most commonly proposed definition for a double-planet system is one in which the barycenter, around which both bodies orbit, lies outside both bodies. Under this definition, Pluto and Charon are double dwarf planets, since they orbit a point clearly outside of Pluto, as visible in animations created from images of the New Horizons space probe in June 2015. Under this definition, the Earth–Moon system is not currently a double planet; although the Moon is massive enough to cause the Earth to make a noticeable revolution around this center of mass, this point nevertheless lies well within Earth. However, the Moon currently migrates outward from Earth at a rate of approximately 3.8 cm (1.5 in) per year; in a few billion years, the Earth–Moon system’s center of mass will lie outside Earth, which would make it a double-planet system. Isaac Asimov suggested a distinction between planet–moon and double-planet structures based in part on what he called a “tug-of-war” value, which does not consider their relative sizes.[5] This quantity is simply the ratio of the force exerted on the smaller body by the larger (primary) body to the force exerted on the smaller body by the Sun. This can be shown to equal

where mp is the mass of the primary (the larger body), ms is the mass of the Sun, ds is the distance between the smaller body and the Sun, and dp is the distance between the smaller body and the primary.[5] The tug-of-war value does not rely on the mass of the satellite (the smaller body). We might look upon the Moon, then, as neither a true satellite of the Earth nor a captured one, but as a planet in its own right, moving about the Sun in careful step with the Earth. From within the Earth–Moon system, the simplest way of picturing the situation is to have the Moon revolve about the Earth; but if you were to draw a picture of the orbits of the Earth and Moon about the Sun exactly to scale, you would see that the Moon’s orbit is everywhere concave toward the Sun. It is always “falling toward” the Sun. All the other satellites, without exception, “fall away” from the Sun through part of their orbits, caught as they are by the superior pull of their primary planets – but not the Moon.[5][6][Footnote 1]

— Isaac Asimov

The origin of the Moon is usually explained by a Mars-sized body striking the Earth, making a debris ring that eventually collected into a single natural satellite, the Moon, but there are a number of variations on this giant-impact hypothesis, as well as alternative explanations, and research continues into how the Moon came to be.[1][2] Other proposed scenarios include captured body, fission, formed together (condensation theory, Synestia), planetesimal collisions (formed from asteroid-like bodies), and collision theories.[3] The standard giant-impact hypothesis suggests that the Mars-sized body, called Theia, impacted the proto-Earth, creating a large debris ring around Earth, which then accreted to form the Moon. This collision also resulted in the 23.5° tilted axis of the Earth, thus causing the seasons. The Moon’s relatively small iron core (compared to other rocky planets and moons in the Solar System) is explained by Theia’s core mostly merging into that of Earth. The lack of volatiles in the lunar samples is also explained in part by the energy of the collision. The energy liberated during the reaccretion of material in orbit around Earth would have been sufficient to melt a large portion of the Moon, leading to the generation of a magma ocean. The newly formed Moon orbited at about one-tenth the distance that it does today, and spiraled outward because of tidal friction transferring angular momentum from the rotations of both bodies to the Moon’s orbital motion. Along the way, the Moon’s rotation became tidally locked to Earth, so that one side of the Moon continually faces toward Earth. Also, the Moon would have collided with and incorporated any small preexisting satellites of Earth, which would have shared the Earth’s composition, including isotopic abundances. The geology of the Moon has since been more independent of the Earth. Although this hypothesis explains many aspects of the Earth–Moon system, there are still a few unresolved problems, such as the Moon’s volatile elements not being as depleted as expected from such an energetic impact.

Fission

This is the now discredited hypothesis that an ancient, rapidly spinning Earth expelled a piece of its mass.[18] This was proposed by George Darwin (son of the famous biologist Charles Darwin) in 1879[20] and retained some popularity until Apollo.[18] The Austrian geologist Otto Ampherer in 1925 also suggested the emerging of the Moon as cause for continental drift.[21] It was proposed that the Pacific Ocean represented the scar of this event.[18] Today it is known that the oceanic crust that makes up this ocean basin is relatively young, about 200 million years old or less, whereas the Moon is much older. The Moon does not consist of oceanic crust but of mantle material, which originated inside the proto-Earth in the Precambrian.[

We are not born over in an old chaos of the sun, but an old chaos of the Cold War / Solar dyad

The Moon, the carcass of a cataclysmic doubling was a signature to the past, they wrote of moonstruckness as the relation of nostalgia, Milan Kundera’s Ignorance, made astronomic (a man and a woman meet by chance while returning to their homeland, which they had abandoned twenty years earlier when they chose to become exiles. Will they manage to pick up the thread of their strange love story, interrupted almost as soon as it began and then lost in the tides of history? The truth is that after such a long absence ‘their memories no longer match’. We always believe that our memories coincide with those of the person we loved, that we experienced the same thing. But this is just an illusion (and in a way he was studying the longitude of Rashomon effects, that tidally resonate out from the initial cataclysm).

The sun came to represent the future, in a way that the human relation to time itself became gravitational, strung between the tidalectics of the moon and the sun, the relation to light and dark, high tide and low, the noontide was bore anew, as a spatial relationality between the dyadic resonances.

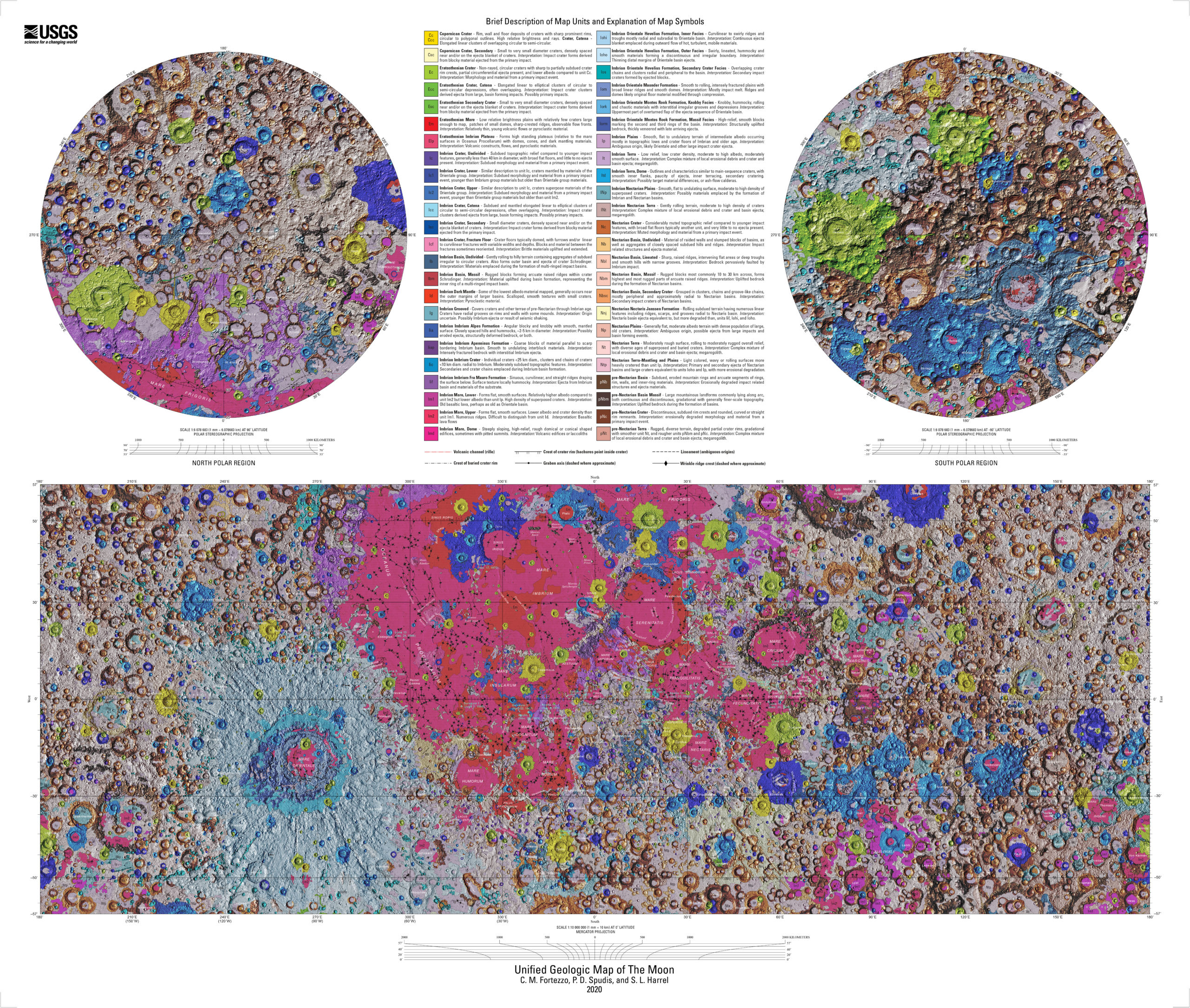

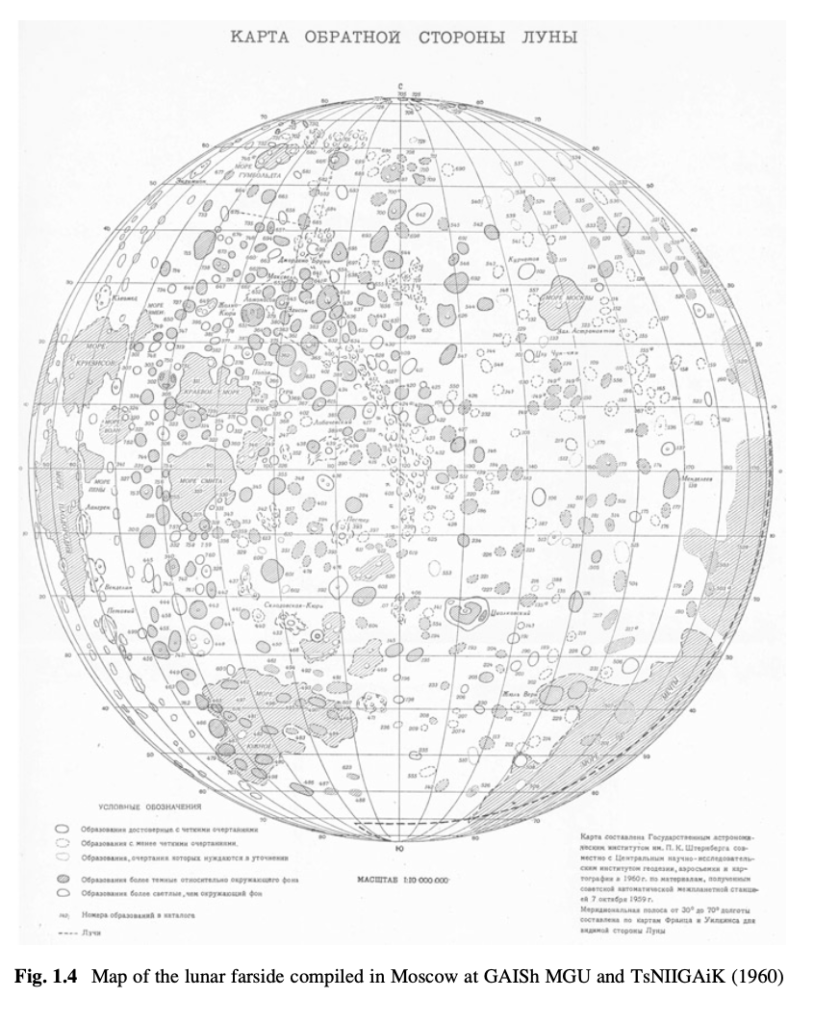

Lunar and Planetary Cartography in Russia (Vladvislav Shevchenko et. al, 2017)

The Moon should, in the near future, become a part of the world civilisation. Its population will, of course, be few. Yet stable outposts will appear for the advancement of science. B. Chertok, 2011.

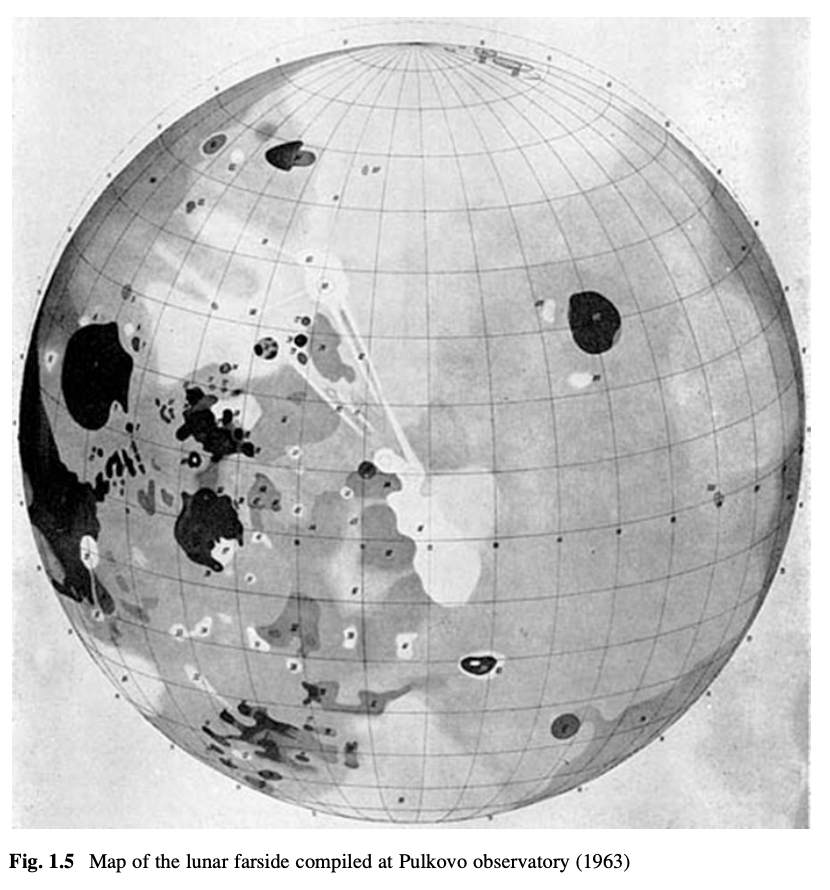

The first Map of the Lunar Far side at 1:10,000,000 scale was published in the Soviet Union on the basis of images of the Luna 3 spacecraft launched from the Baikonur cosmodrome on 4th October 1959. New methods for processing the original photographic images developed by Yu. N. Lipsky largely eliminated the radio interference enabling the identification of many real features of the lunar terrain. The newly discovered surface features were compiled onto a map using a unified selenographic coordinate system. The Atlas of the Lunar Farside, published in 1960, includes 30 photographs taken by Luna 3, the results of their analysis and a catalogue with detailed descriptions of 729 identified features. The first globe, showing the nearside and a part of the farside. was produced in 1961.

Academician Boris Evseyevich Chertok – the legendary spacecraft engineer, comrade-in-arms and deputy of Chief Designer Sergei Pavlovich Korolev – described in his memoirs of the distant events of October 1959 the moment of receiving the first images from the farside of the Moon (Chertok 1996, 2006):

I took a place beside Boguslavsky at the apparatus for recording on electrochemical paper. From the receiving station they reported:

— Range: fifty thousand. Signal stable. Receiving!

The command was given to produce the image. Again the responsibility was with FTU. Line by line on the paper, a grey image began to appear. A disc which, with sufficient

imagination, details could be distinguished.

Impatiently, Korolev burst into our cramped little room.

— Well, what have you got there?

— We’ve found that the Moon is round — I said.

Boguslavsky pulled the recorded image from the apparatus, showed it to Korolev, and

calmly tore it up. Sergei Pavlovich didn’t raise an eyebrow.

— Why so soon, Evgenii Yakovlevich? It’s just the first, you know – just the first!

— It’s bad – such a muddy image. Now we’ll get rid of the interference, and the next

frames will be OK.

One after the other, the images appeared on the paper, each more distinct than the last. We cheered and congratulated each other. Boguslavsky reassured us that on the photo- graphic film, which was being processed in Moscow, everything would be much better.

1959 became the beginning of a new era in lunar mapping. As far as we know, there were no maps of the Moon published in Russia before 1960. However, the world’s first Map of the lunar farside was published in the USSR. The Soviet interplanetary spacecraft Luna 3 imaged the Moon for 40 minutes on 7th October 1959 (Pervye fotografii obratnoy storonu Luny 1959) (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). As a part of the development of the technology for the photography and image transmission, it was necessary to build an orientation system, consisting of optical and gyroscopic sensors, electronic logic units, and steering thrusters to point the spacecraft in the required direction. The photography was done using a camera with two objectives, having different focal lengths. The film was developed, fixed, rinsed and dried automatically on board. The image was transmitted on command from Earth to a ground-based receiving station (Mikhailov and Straut 1968). Images of the eastern part of the nearside and the western part of the farside were transmitted by radio to Earth (Fig. 1.3).